Does employment status predict addiction treatment outcome? Yes and no

Addiction professionals tend to think about the ways addiction adversely affects employment, but historically have thought less about how employment might actually influence addiction recovery outcomes. In this study, the authors asked, “what if people’s employment status at the start of, and during, addiction treatment influences recovery outcomes, and if so, what specific features of employment matter most?”

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Employment provides fulfillment of basic needs of survival, relatedness, and self-determination. For people entering recovery, it can provide important structure as well as meaning and purpose for some. It has been suggested that enhancing employment of those with substance use disorders (SUD) may support long-term recovery. Employment among those in AUD recovery is also associated with better quality of life, and greater self-esteem and happiness. However, simply focusing on SUD treatment’s effect on employment, may miss the benefits employment serves in recovery. With this in mind, more recently, researchers have begun to investigate associations between employment and treatment completion. Current research, however, has yet to identify employment factors that support recovery, and few employment-focused post-treatment studies exist.

This study sought to address this knowledge gap by investigating whether employment variables at the start of SUD treatment, and change in these employment measures during treatment, predict successful treatment completion and substance use at six-month follow-up. Finally, the authors investigated which employment variables were most strongly associated with abstinence at six-month follow-up.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a retrospective analysis of state health records of 8,925 individuals who had been admitted to Iowa SUD treatment programs including medically monitored residential, clinically managed residential, intensive outpatient, and standard outpatient facilities. Data were collected at treatment admission, discharge, and six-month follow-up.

These data are compiled and stored in the Iowa Central Data Repository by the Iowa Department of Public Health, and are merged with electronic health files and assembled into a client management system. The Iowa Consortium for Substance Abuse Research and Evaluation select yearly random samples from this treatment data, conduct six-month follow-up telephone interviews, and compile follow-up data into the Outcomes Monitoring System. Each Outcomes Monitoring System response set includes a merged single treatment episode including admission, treatment discharge, and follow-up interview data. For this research, the Iowa Department of Public Health approved the use of a deidentified Outcomes Monitoring System dataset for years 1999 to 2016.

The full sample (N= 8,925) were a mean age of 31.7 (SD=11.8), mostly male (67.2%), primarily White (86.6%) and non-Hispanic/Latino (96.1%). Outpatient care comprised the majority of services with extended outpatient (63.6%) and intensive outpatient (17.5%) settings. Most clients completed treatment successfully (61.2%).

SUD treatment outcome measures.

Three outcome variables were tested: 1) SUD treatment completion; 2) alcohol and other drug abstinence; and 3) total substance use.

Employment measures.

Employment measures included: 1) employment (full-time, part-time, unemployed/looking, and not in labor force); 2) occupation (none, professional/managerial, sales/clerical, crafts/operatives, laborers, farm, and service/household); 3) primary support (none, wages, family/friends, public assistance including all federal/state income programs, retirement, disability, and other); 4) past six months employment (months employed); 5) work missed (past month days of work missed due to substance use); and 6) gross income.

Employment change measures.

Change in each of the six employment measures from treatment admission to six-month follow-up were coded as increased, no change, or decreased. Continuous variables (i.e., months employed, work missed, gross income) were simply categorized by change at follow-up. Primary financial support consisted of wages, other supports, and no support. A change from no support to other support (i.e., friends and family, public assistance) was determined to be an increase. Occupation was coded as no occupation or any occupation. Employment was categorized as full time, part time, unemployed-looking, or out of the labor force.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

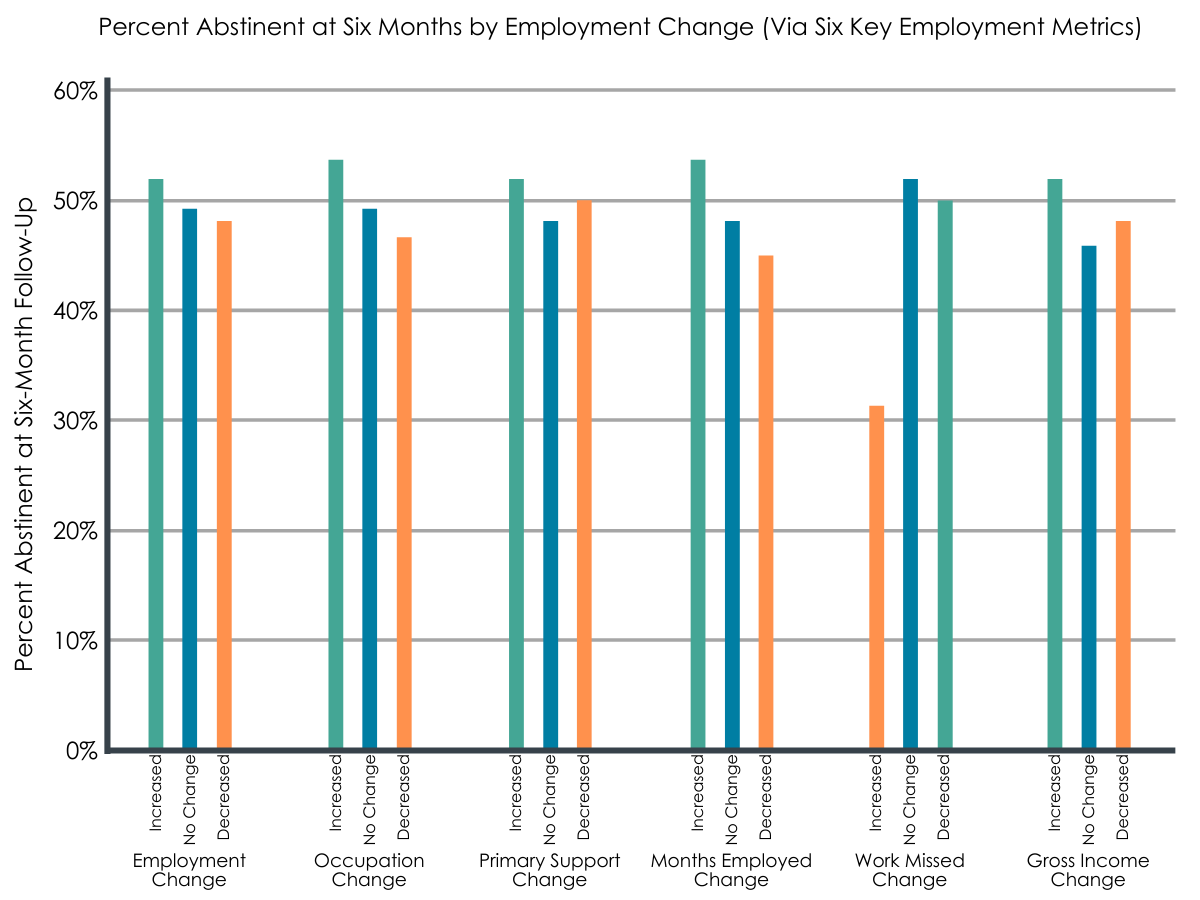

Figure 1.

Employment at the start of treatment was associated with greater likelihood of completing treatment.

- Generally speaking, those who were employed at the start of treatment were more likely to complete treatment. Those employed full-time when entering treatment were 9.1% more likely to complete treatment versus not, while conversely, those who were unemployed and looking for work were 8.4% less likely to complete treatment. In terms of influence of occupation type on treatment completion, results indicated that it is not so much important what one does for a living; rather, that one has some kind of job.

- Additionally, those who had worked more in the past six months prior to entering treatment were statistically significantly (meaning there is very small likelihood the observed difference is a result of chance) more likely to complete treatment, though the actual difference was not clinically meaningful.

- With regards to days of work/school missed in the past month prior to entering treatment, treatment completers missed on average 2.1 less days of work or school in the month prior to starting treatment compared to non-finishers. Treatment completers also earned on average US$133 more in the past month prior to starting treatment initiation compared to non-finishers.

Employment at the start of treatment was associated with lower likelihood of being abstinent at six-month follow-up.

- Contrary to the authors’ prediction, being ‘employed’ at treatment admission was associated with lower likelihood of being abstinent or having reduced substance use at six-month follow-up. Conversely, those who were ‘unemployed and looking for work’ and ‘not in the labor force’ were significantly more likely to have reduced their substance use at six-month follow-up. Also, those who had worked more in the past six months prior to entering treatment were significantly more likely to have maintained substance use versus reduced.

- With regards to days of work/school missed in the past month prior to entering treatment, those who missed less days of work/school were more likely to have reduced their substance use versus maintained.

- Clients with greater monthly income at treatment initiation were also more likely to have maintained substance use than been abstinent, and more likely to have maintained use than reduced, though again, the actual differences in terms of income were not great.

Improving employment status during or following treatment was associated with greater likelihood of being abstinent at six-month follow-up.

- Increases and no change in employment status from admission to follow-up were associated with the greater abstinence at follow-up. Relatedly, more days of work missed due to substance use was associated with a 2.7 times lower probability of abstinence than ‘no change in work missed’, and a 2.4 times lower probability of abstinence than ‘decreased work missed’. Additionally, those with ‘increased months employed’ were 1.5 times more likely to be abstinent compared to those with ‘decreased months employed’.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

While some of the authors’ results are intuitive, the unexpected finding of certain employment measures being associated with worse treatment outcomes—at least in terms of substance use—make clinical application of these findings challenging.

Though being employed at treatment entry was associated with greater maintained/increased substance use at six-month follow-up, it would of course not be recommended that people quit their job when entering SUD treatment. It is possible that employment and associated stress and time management difficulties may create vulnerability for SUD relapse. It is also possible that individuals employed at the start of treatment have lower addiction severity by virtue of the fact that they are actually still working, and that a portion of these individuals pursued substance use moderation goals following treatment rather than total abstinence.

The finding that improvement in employment status predicts greater abstinence at follow-up, rather than simply securing employment per se is noteworthy. On one hand it appears that improving employment status, no matter what level one begins with at treatment admission, leads to better long-term SUD recovery outcomes. It may be that improvements in employment status reflects behaviors incompatible with substance use, whereas existing employment prior to treatment admission may not provide the same behavior-change effects. With this in mind, SUD interventions may see greater success when focused on enhancing employment and certain aspects of employment. Developing improved self-efficacy and outcome expectations of employment may be helpful in SUD treatment. It is also possible however that improvements in substance use lead to improvements in employment status. That is, it is possible individuals who were able to maintain abstinence following treatment were simply more able to get and maintain a new job. Further prospective research is needed to untangle this.

Regardless, the clinical implication here is that helping patients improve their employment status is more important than only helping those who are unemployed find work. It may not matter where a client begins in terms of employment. Rather, improvement may be the important factor contributing to recovery. In other words, helping those who are unemployed find any kind of work (part- or full-time) matters, as does helping those who are employed part-time find full-time work or more meaningful work. Recovery community centers could be a great resource to support these kinds of job transitions.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As noted by the authors, they were limited in the employment measures they could assess because data for this study were extracted from a pre-existing dataset.

- Also, these findings are not generalizable to the entire United States, although they are generalizable to a meaningful proportion of addiction treatment seekers in the United States who have lower socioeconomic status.

- Because they were limited to using pre-existing data, the authors did not have a robust measure of addiction severity to control for in the regression models, although they did include number of individuals’ problem substances to approximate this.

- The direction of the relationship between change in employment status and SUD relapse cannot be known from these data.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: In this study, the authors found that being employed at treatment entry was associated with poorer substance use outcomes at six-month follow-up; however, improving one’s employment status during treatment was associated with higher likelihood of abstinence. Increasing one’s employment engagement such as increasing work from unemployed to part-time, and part- to full-time work may confer benefits in terms of substance use treatment outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: In this study, the authors found that being employed at treatment entry was associated with poorer substance use outcomes at six-month follow-up, however, improving one’s employment status during treatment was associated with higher likelihood of abstinence. Helping individuals increase their employment engagement such as increasing work from unemployed to part-time, and part- to full-time work may confer benefits in terms of substance use treatment outcomes. Treatments incorporating employment goals may benefit from developing feedback informed goals highlighting employment change and improvement.

- For scientists: In this study, the authors found that being employed at treatment entry was associated with poorer substance use outcomes at six-month follow-up, however, improving one’s employment status during treatment predicted greater abstinence. Research is needed that can more deeply explore the nuances of this study’s findings, particularly the counterintuitive result showing those employed at treatment entry had poorer substance use outcomes six months following treatment, possibly due to addiction severity and substance use impairment factors.

- For policy makers: In this study, then authors found that being employed at treatment entry was associated with poorer substance use outcomes at six-month follow-up, however, improving one’s employment status during treatment predicted greater abstinence. Findings highlight the value in helping individuals in early addiction recovery increase employment and speak to the need to reducing barriers to work and supporting job creation programs for individuals trying to resolve a SUD.

CITATIONS

Sahker, E., Ali, S. R., & Arndt, S. (2019). Employment recovery capital in the treatment of substance use disorders: Six-month follow-up observations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107624. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107624