Do Anti-psychotic Medications Treat Cocaine Use Disorder?

Currently there are no medications approved for the treatment of cocaine use disorder despite approximately 1.6 million Americans reportedly using the drug.

Researchers have conducted numerous animal studies and human clinical trials attempting to discover what medication can treat patients with cocaine use disorder in a manner similar to the use of buprenorphine for individuals with opioid use disorder. There have been mixed results regarding the use of antipsychotics for the treatment of cocaine use disorder in patients without mental disorders for which the drugs are clinically indicated (ie., bipolar disorder or schizophrenia).

Since dompaminergic and serotonergic receptors may play a role in the reinforcing effects of cocaine, it is thought that antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine (brand name Seroquel) may block these receptors, reducing this reinforcing effect and ultimately reducing cravings. A previous open-label (i.e., participants and researchers were aware of the medication administered) pilot study examining quetiapine use in non-psychotic volunteers meeting DSM-IV criteria for cocaine dependence had found significant reductions in cocaine cravings over time.

Building on the prior research, Tapp et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine to further estimate its efficacy in treating cocaine use disorder among individuals without psychosis. Participants (N = 60) meeting DSM-IV criteria for cocaine dependence who used cocaine within the past 30 days and did not have a psychotic disorder were randomized to once daily oral quetiapine (n = 29) or matched placebo (n = 31).

Participants were 48 years old on average, 87% male, and 64% African American. The average length of cocaine use was 20 years. There were no differences between groups in terms of baseline characteristics.

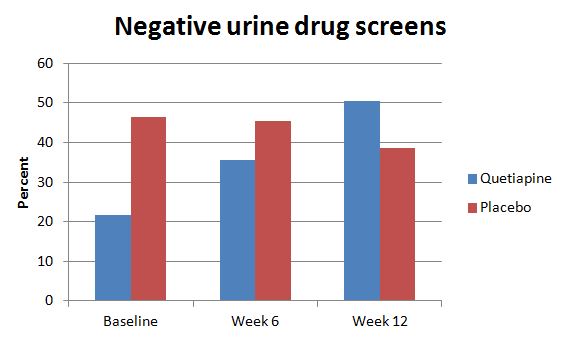

By week 12, 68% of participants had dropped out of the study. Of the participants completing the study, 10 were in the quetiapine group and 8 were in the placebo group. There was no differential drop out by group. Of those completing the study, 30% achieved abstinence (i.e., negative urine drug screen for cocaine for three consecutive weeks), though there was no significant difference between groups in terms of end of trial abstinence.

The authors found no significant differences between groups in cocaine use, money spent on cocaine, or cravings for cocaine.

The authors performed intention-to-treat (i.e., including all participants as randomized) analyses with two different assumptions. The first assumed that all participants who dropped out had relapsed (not achieved the outcome) and the second assumed drop out occurred due to random reasons and used the last observation before drop-out in the analysis. Both assumptions and analyses resulted in no significant differences between groups.

IN CONTEXT

While quetiapine does not appear to be effective for the treatment of cocaine use disorder due to lack of significant differences between groups, this study still adds valuable information for scientists in the search for the elusive solution to medication-assisted treatment for this specific substance.

For this study, high drop-out rate was most likely due to the characteristics of the population under study rather than the medication itself as drop-out rates were similar between groups. These individuals on average had used cocaine for about 20 years and thus were very long-term cocaine users. Regardless, individuals with cocaine use disorder, seem difficult to retain in treatment, with several other studies reporting similarly high drop-out rates. Research suggests this is a difficult population to treat.

Other antipsychotic medications examined in randomized controlled trials have shown lack of efficacy in non-psychotic cocaine-using populations meaning that scientists may need to look to other classes of drugs for a medical treatment for cocaine use disorder.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- One limitation of the study was the high rate of drop-out which decreased statistical power for the analyses. Lack of power aside, intention-to-treat analyses still pointed towards inefficacy of quetiapine.

NEXT STEPS

When using data presented by the authors to calculate effect size estimates for between group differences in outcomes at week 12, Cohen’s d ranged between 0.5 and 0.6 which is indicative of a medium effect size. While not statistically significant, these results may still be clinically meaningful. This may warrant further research into quetiapine’s effectiveness with a larger sample.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: While there is no medication available for treating cocaine use disorder, psychosocial treatments are available. More frequent visits and longer duration of intervention are associated with better outcomes. Evidence-based treatments including individual, 12-step focused drug counseling which appear to better retain patients in treatment with about 50% still engaged after 3 months.

- For scientists: Due to the effect sizes detected from this data, a larger trial evaluating the efficacy of quetiapine for cocaine use disorder may be warranted, perhaps with additional psychosocial treatment and/or motivational incentives to enhance treatment retention. Other promising medications from animal studies or open-label trials should be evaluated through randomized controlled trials with special attention to attrition.

- For policy makers: Continued appropriation of funding is needed to help find pharmacological and other effective treatments for cocaine use disorder.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Try to retain patients with cocaine use disorder in treatment since this population has high rates of loss to follow-up and long average length of use. Implementation of motivational incentives has been shown to help (see here).

CITATIONS

Tapp, A., Wood, A. E., Kennedy, A., Sylvers, P., Kilzieh, N., & Saxon, A. J. (2015). Quetiapine for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. Drug and alcohol dependence.