Low-risk alcohol use guidelines have been established to help reduce alcohol-related health problems. This study evaluated whether a mass media campaign improved knowledge of low-risk alcohol use guidelines and related health risks.

Low-risk alcohol use guidelines have been established to help reduce alcohol-related health problems. This study evaluated whether a mass media campaign improved knowledge of low-risk alcohol use guidelines and related health risks.

l

Alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of disease and disability through several potential health problems, such as hypertension and cancer. As a result, public health officials have established recommended guidelines for alcohol consumption levels to prevent such problems. For instance, in the US it is recommended that, for those who choose to drink, men limit alcohol use to 2 standard drinks or less per day and women limit alcohol use to 1 standard drink or less per day. In France, where this study took place, it is recommended that both men and women should not consume more than 10 standard drinks per week, no more than 2 standard drinks per day, and should have at least 2 alcohol-free days per week. Of note, the definition of a “standard drink” differs by country; in the US, a standard drink is defined as 14 grams of pure alcohol, while in France, it is 10 grams.

In the US, approximately 36% of people reported a heavy drinking session in the last 30 days, and in France, this percentage is 41.5%. A heavy drinking episode was defined as consuming 60 or more grams of pure alcohol, which is equivalent to 4 standard drinks in the US and 6 in France. This may be due, in part, to lack of awareness of health risks, as more than 50% of Americans are unaware that alcohol increases risk of cancer, and lack of awareness of the low-risk drinking guidelines.

Mass media campaigns may help increase the knowledge about alcohol-related health risks and drinking guidelines, reaching many people over a short time period. Researchers in this study evaluated the effectiveness of such a campaign in France. This research can help shed light on whether mass media campaigns intended to improve public health make a difference in the public’s knowledge and health behaviors.

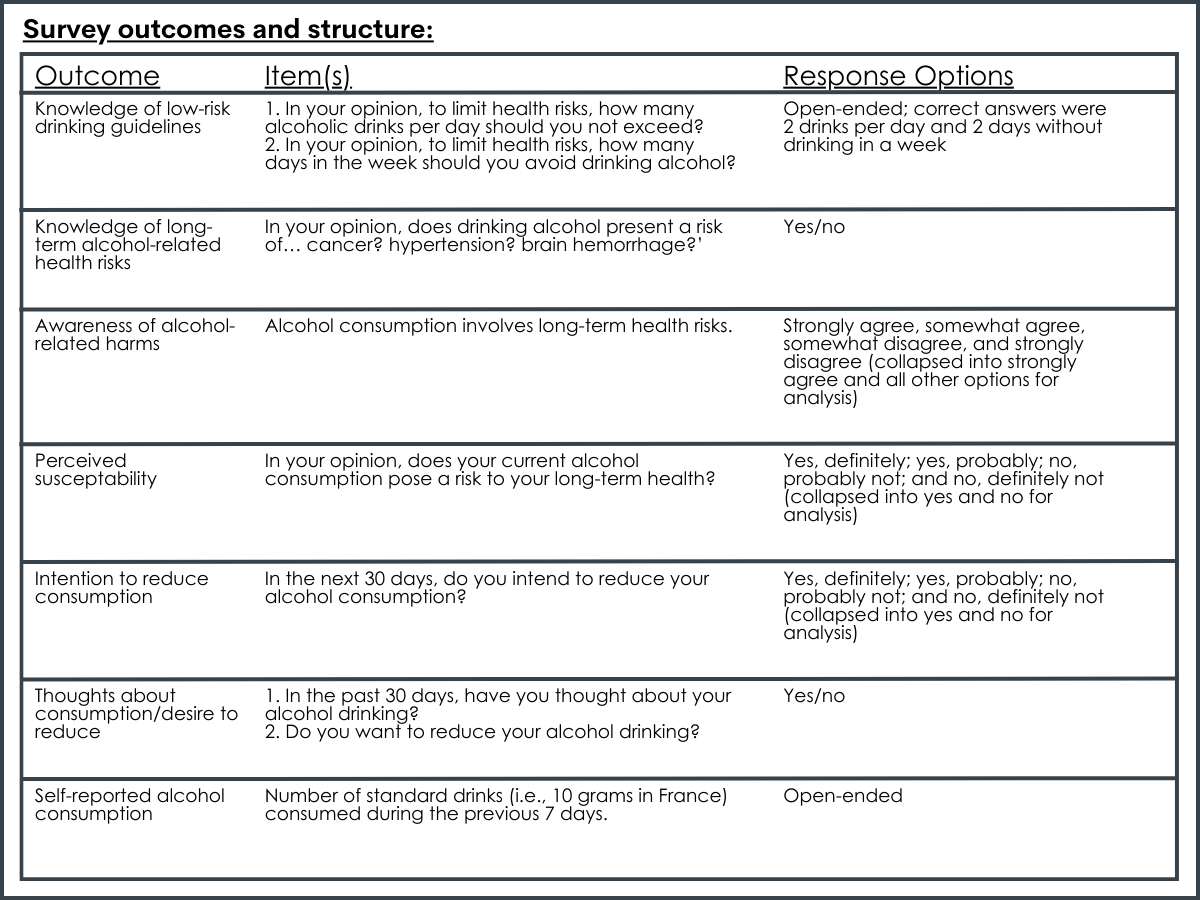

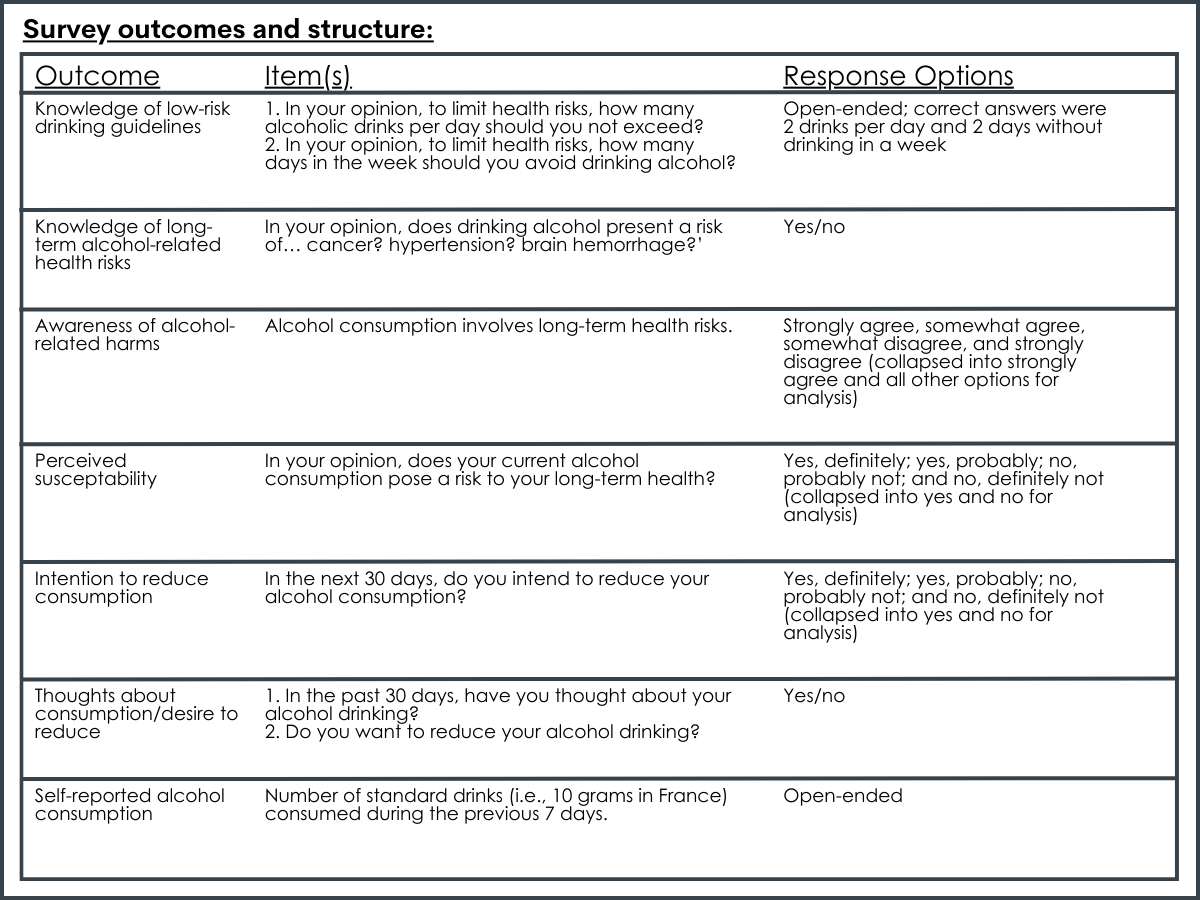

This study evaluated a mass media campaign in France by comparing recollections of having been exposed to the campaign or not, that aimed to improve the public’s knowledge of low-risk drinking guidelines and alcohol-related health risks and thereby reduce alcohol consumption. The campaign was broadcast for 1 month and surveys were conducted prior to the campaign, immediately after it ended, and 6 months after it ended.

The audio/visual campaign was broadcast through popular TV and social media advertisements. The campaign’s primary advertisement showed actors in different situations with a voice-over saying that alcohol does not have to end with a disaster (e.g., a car accident or a fight) and then explaining that more 2 drinks a day increases risk of a brain hemorrhage, cancer, and hypertension. It ended with the campaign slogan: “For your health, no more than two alcohol drinks per day. And not every day.” In addition to this advertisement, advertisements and videos were also broadcast online and in health facilities, interviews with addiction experts were broadcast on national radio stations, and posters were hung in health care settings.

During the first follow up survey (right after the campaign ended), the researchers also assessed exposure to the campaign with self-reported and assisted campaign recall. Each campaign item (i.e., advertisements, radio interviews, posters, etc.) was shown in random order and participants were asked if they remember having seen or heard each one. If yes, they were considered to be in the “exposed” group.

To be eligible for the study, participants had to have reported drinking alcohol in the last 12 months, as assessed via a screening question that was adapted from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) questionnaire. The research team recruited a sample of 4002 people between the ages of 18 and 75 to complete an online survey. The sample was nationally representative, but was limited to those with access to the Internet. Of the 4002 participants who responded to the baseline survey, 3005 completed the first follow up survey immediately after the campaign ended, and 2538 completed the second follow up survey 6-months after the campaign ended. These people were included in the analyses. Women (vs. men) and younger individuals (vs. older) were more likely to miss a follow-up assessment.

At the first follow-up survey, they also recruited a new sample of 501 participants to test whether any potential benefit of the campaign was attributable to exposure to the campaign itself and not a combination of the campaign and initial questionnaires that primed individuals to pay more attention to the campaign. They hypothesized that if there are differences between the 2 groups at the first follow up immediately following the campaign, then there is likely a priming effect accounting for at least some of the campaign benefits.

Differences between exposed and unexposed groups.

Among all participants, 74.5% reported recognizing at least one campaign item (i.e., the exposed group), with the majority (67%) recognizing the TV ad.

Participants in the exposed group were older than those in the unexposed group, with 74.5% of exposed participants being older than 35 years, compared to 67.7% of unexposed participants. Participants in the exposed group also had lower levels of education, with 27.7% having less than an upper secondary school certificate (equivalent to a high school diploma in the US), versus 21.7% in the unexposed group.

Before the campaign (i.e., baseline assessment), participants ultimately exposed to the campaign were slightly more likely to report thinking about their drinking in the previous 30 days (16.0% versus 12.4%, respectively) and to report a desire to reduce their alcohol consumption (22.7% versus 18.8%, respectively).

Campaign exposure improved short-term knowledge and reduced alcohol consumption, but for some groups more than others.

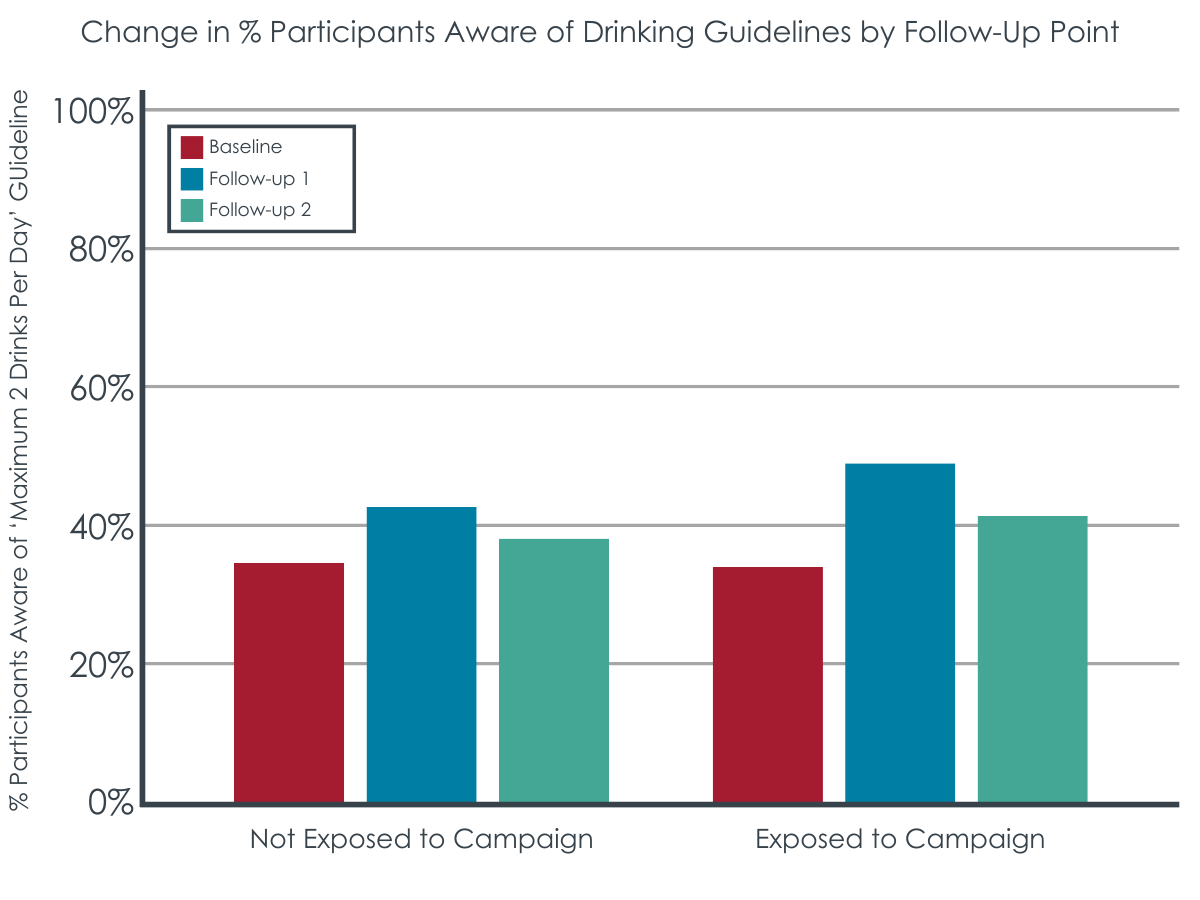

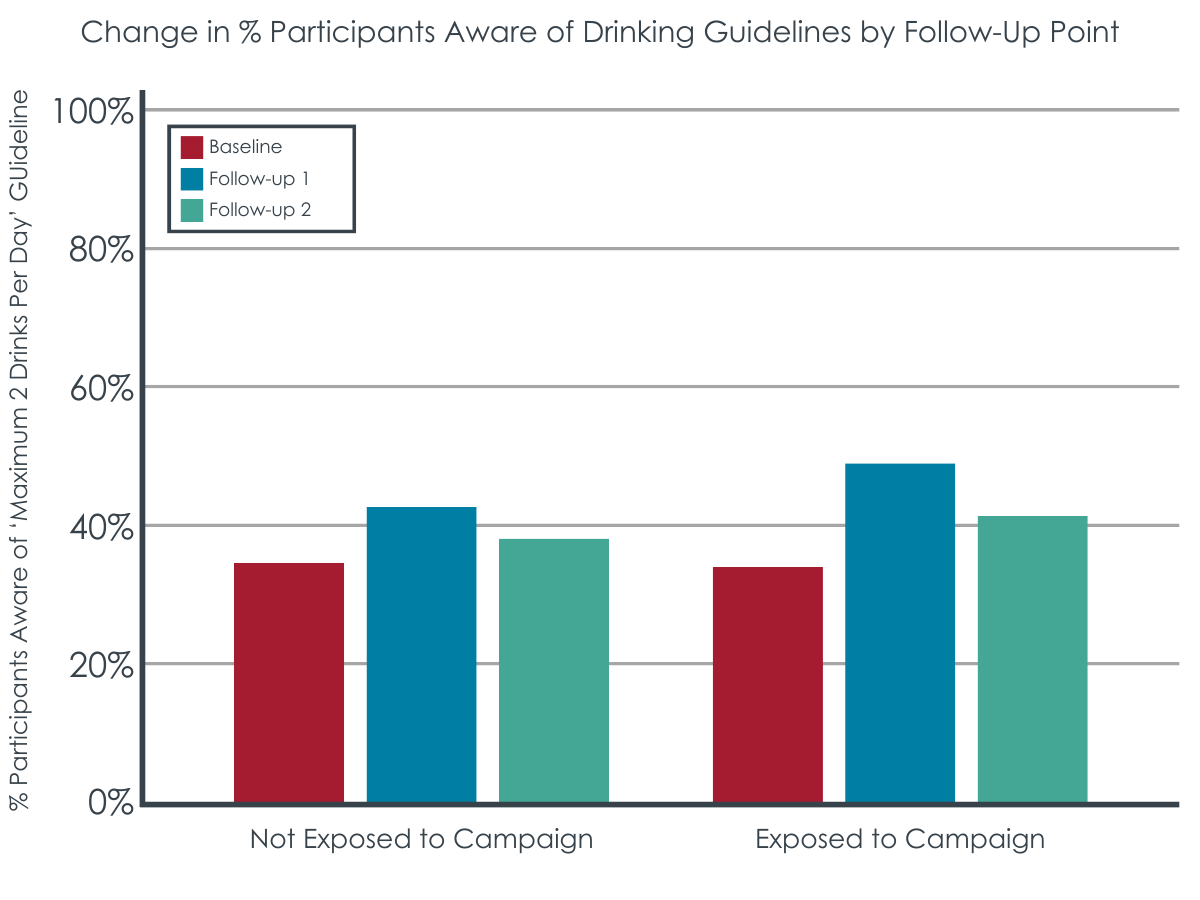

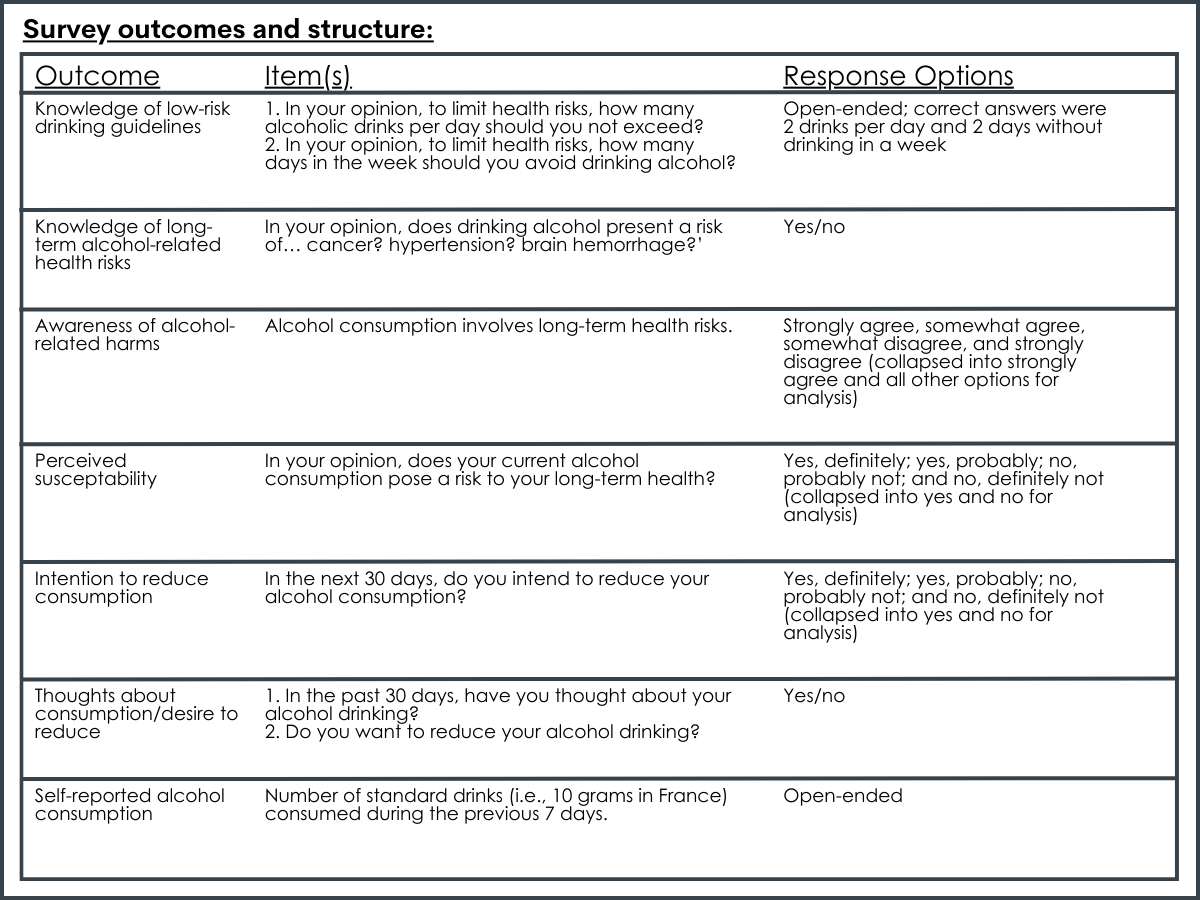

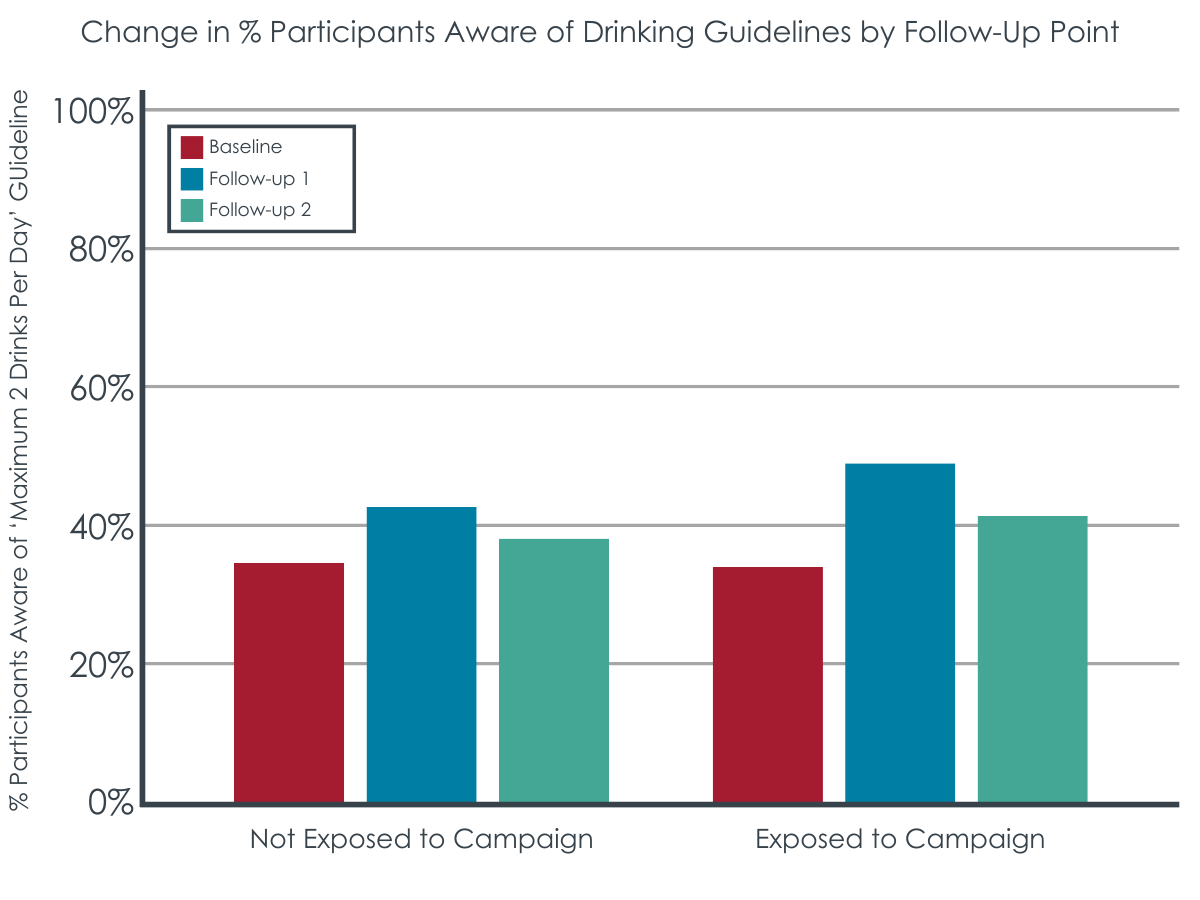

At the first follow-up survey immediately after the campaign ended, the exposed group was more likely to report knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline than the unexposed group. However, there were no differences between groups in knowledge of the ‘minimum of 2 days without alcohol a week’ guideline. At the second follow-up survey 6 months after the survey ended, there were no differences between groups for either guideline.

Also at the first follow-up survey, the exposed group was more likely to report knowledge of the risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage than the unexposed group. However, at the second follow-up, there were no differences between groups for any of the health risks. There were no differences between groups at either follow-up survey for perceived susceptibility and intention to reduce alcohol consumption in the next 30 days.

The effect of campaign exposure on alcohol-related hypertension knowledge differed by socioeconomic status, however. There was improved knowledge of risk for alcohol-related hypertension risk at the first follow-up survey among those in high socio-professional categories (e.g., managers, farmers, retailers, business owners), but not among those in low socio-professional categories (e.g., clerical workers, manual workers).

For alcohol consumption, there were fewer participants in the exposed group who reported drinking more than recommended by the low-risk drinking guidelines (i.e., more than a total of 10 standard drinks during the previous 7 days, and/or more than two drinks in any

day during the previous 7 days, and/or drinking on more than five of the previous 7 days) than those in the unexposed group at the first follow-up survey. However, at the second follow-up, there were no differences between groups in self-reported alcohol consumption. When examining effects of exposure by gender, findings showed this effect of campaign exposure on adhering to low-risk drinking guidelines was associated with benefit in women, but not in men, at the first follow-up survey.

Finally, among people who reported exceeding drinking guidelines at baseline, campaign exposure was associated with improved knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline and risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage, similar to the campaign effects across all participants.

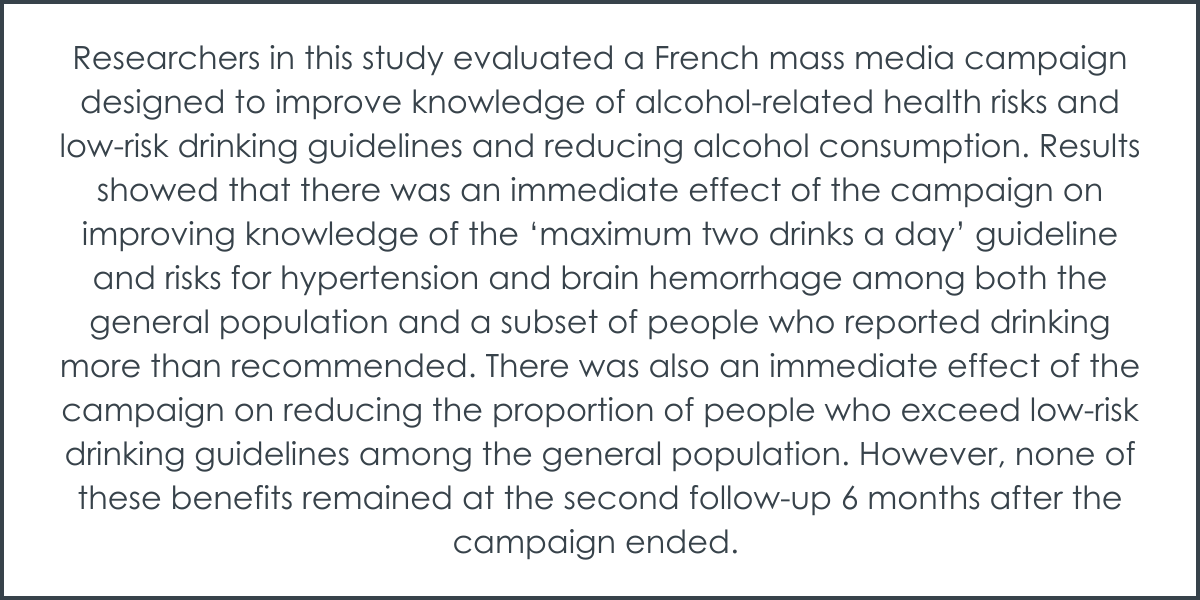

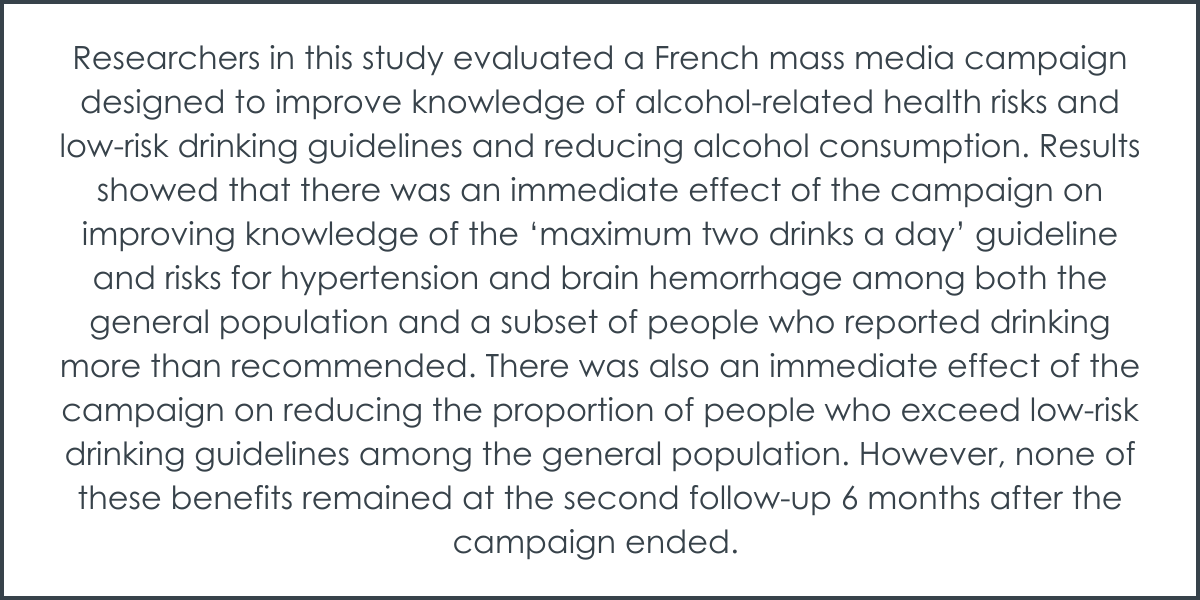

Researchers in this study evaluated a French mass media campaign designed to improve knowledge of alcohol-related health risks and low-risk drinking guidelines and reducing alcohol consumption. Results showed that there was an immediate effect of the campaign on improving knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline and risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage among both the general population and a subset of people who reported drinking more than recommended. There was also an immediate effect of the campaign on reducing the proportion of people who exceed low-risk drinking guidelines among the general population. However, none of these benefits remained at the second follow-up 6 months after the campaign ended.

Results also showed that campaign exposure improved knowledge of health risks and guidelines among people who reported drinking more than recommended by the guidelines. This is notable because reducing risks for people who drink in potentially harmful ways is likely to have an even greater positive impact on public health and possibly public safety as well (e.g., reduced driving while over the legal limit). At the population level, this could exert a large-scale public health impact even though the immediate effects were relatively small.

The benefits of the campaign on reduced drinking being stronger in women may be partially due to women drinking less alcohol overall than men. Thus, for women who were not already drinking within the guidelines, they may not have had to remove as many as drinks as men to meet the low-risk guidelines. This finding may also be due to women typically being more concerned about their health than men. Nonetheless, it is particularly important, given that women are more sensitive to the effects of alcohol and develop negative health consequences sooner.

Although the campaign was associated with short-term effects, its inability to produce long-term changes in alcohol consumption is consistent with other research showing the limitations of alcohol-related public health campaigns in reducing alcohol consumption over the long term. For youth specifically, the substantial amount of evidence showing that the widely popular Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) is ineffective in reducing drug use further points to the need for public health prevention and intervention to go beyond raising awareness and improving education to directly target key risk factors (e.g., teaching social and emotional skills; promoting parental monitoring and nurturance through parent-based interventions; promoting alternative behavioral strategies and a sense of community).

A mass media campaign designed to improve knowledge of alcohol-related health risks and low-risk drinking guidelines and reduce alcohol consumption had a short-term effect on these outcomes, but the effects did not last long-term. Accordingly, mass media campaigns may be helpful immediately, but in the absence of additional approaches that target risk factors at both individual and community levels on an ongoing basis, are unlikely to produce sustained behavior change.

Quatremère, G., Guignard, R., Cogordan, C., Andler, R., Gallopel‐Morvan, K., & Nguyen‐Thanh, V. (2023). Effectiveness of a French mass‐media campaign in raising knowledge of both long‐term alcohol‐related harms and low‐risk drinking guidelines, and in lowering alcohol consumption. Addiction, 118(4), 658-668. doi: 10.1111/add.16107

l

Alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of disease and disability through several potential health problems, such as hypertension and cancer. As a result, public health officials have established recommended guidelines for alcohol consumption levels to prevent such problems. For instance, in the US it is recommended that, for those who choose to drink, men limit alcohol use to 2 standard drinks or less per day and women limit alcohol use to 1 standard drink or less per day. In France, where this study took place, it is recommended that both men and women should not consume more than 10 standard drinks per week, no more than 2 standard drinks per day, and should have at least 2 alcohol-free days per week. Of note, the definition of a “standard drink” differs by country; in the US, a standard drink is defined as 14 grams of pure alcohol, while in France, it is 10 grams.

In the US, approximately 36% of people reported a heavy drinking session in the last 30 days, and in France, this percentage is 41.5%. A heavy drinking episode was defined as consuming 60 or more grams of pure alcohol, which is equivalent to 4 standard drinks in the US and 6 in France. This may be due, in part, to lack of awareness of health risks, as more than 50% of Americans are unaware that alcohol increases risk of cancer, and lack of awareness of the low-risk drinking guidelines.

Mass media campaigns may help increase the knowledge about alcohol-related health risks and drinking guidelines, reaching many people over a short time period. Researchers in this study evaluated the effectiveness of such a campaign in France. This research can help shed light on whether mass media campaigns intended to improve public health make a difference in the public’s knowledge and health behaviors.

This study evaluated a mass media campaign in France by comparing recollections of having been exposed to the campaign or not, that aimed to improve the public’s knowledge of low-risk drinking guidelines and alcohol-related health risks and thereby reduce alcohol consumption. The campaign was broadcast for 1 month and surveys were conducted prior to the campaign, immediately after it ended, and 6 months after it ended.

The audio/visual campaign was broadcast through popular TV and social media advertisements. The campaign’s primary advertisement showed actors in different situations with a voice-over saying that alcohol does not have to end with a disaster (e.g., a car accident or a fight) and then explaining that more 2 drinks a day increases risk of a brain hemorrhage, cancer, and hypertension. It ended with the campaign slogan: “For your health, no more than two alcohol drinks per day. And not every day.” In addition to this advertisement, advertisements and videos were also broadcast online and in health facilities, interviews with addiction experts were broadcast on national radio stations, and posters were hung in health care settings.

During the first follow up survey (right after the campaign ended), the researchers also assessed exposure to the campaign with self-reported and assisted campaign recall. Each campaign item (i.e., advertisements, radio interviews, posters, etc.) was shown in random order and participants were asked if they remember having seen or heard each one. If yes, they were considered to be in the “exposed” group.

To be eligible for the study, participants had to have reported drinking alcohol in the last 12 months, as assessed via a screening question that was adapted from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) questionnaire. The research team recruited a sample of 4002 people between the ages of 18 and 75 to complete an online survey. The sample was nationally representative, but was limited to those with access to the Internet. Of the 4002 participants who responded to the baseline survey, 3005 completed the first follow up survey immediately after the campaign ended, and 2538 completed the second follow up survey 6-months after the campaign ended. These people were included in the analyses. Women (vs. men) and younger individuals (vs. older) were more likely to miss a follow-up assessment.

At the first follow-up survey, they also recruited a new sample of 501 participants to test whether any potential benefit of the campaign was attributable to exposure to the campaign itself and not a combination of the campaign and initial questionnaires that primed individuals to pay more attention to the campaign. They hypothesized that if there are differences between the 2 groups at the first follow up immediately following the campaign, then there is likely a priming effect accounting for at least some of the campaign benefits.

Differences between exposed and unexposed groups.

Among all participants, 74.5% reported recognizing at least one campaign item (i.e., the exposed group), with the majority (67%) recognizing the TV ad.

Participants in the exposed group were older than those in the unexposed group, with 74.5% of exposed participants being older than 35 years, compared to 67.7% of unexposed participants. Participants in the exposed group also had lower levels of education, with 27.7% having less than an upper secondary school certificate (equivalent to a high school diploma in the US), versus 21.7% in the unexposed group.

Before the campaign (i.e., baseline assessment), participants ultimately exposed to the campaign were slightly more likely to report thinking about their drinking in the previous 30 days (16.0% versus 12.4%, respectively) and to report a desire to reduce their alcohol consumption (22.7% versus 18.8%, respectively).

Campaign exposure improved short-term knowledge and reduced alcohol consumption, but for some groups more than others.

At the first follow-up survey immediately after the campaign ended, the exposed group was more likely to report knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline than the unexposed group. However, there were no differences between groups in knowledge of the ‘minimum of 2 days without alcohol a week’ guideline. At the second follow-up survey 6 months after the survey ended, there were no differences between groups for either guideline.

Also at the first follow-up survey, the exposed group was more likely to report knowledge of the risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage than the unexposed group. However, at the second follow-up, there were no differences between groups for any of the health risks. There were no differences between groups at either follow-up survey for perceived susceptibility and intention to reduce alcohol consumption in the next 30 days.

The effect of campaign exposure on alcohol-related hypertension knowledge differed by socioeconomic status, however. There was improved knowledge of risk for alcohol-related hypertension risk at the first follow-up survey among those in high socio-professional categories (e.g., managers, farmers, retailers, business owners), but not among those in low socio-professional categories (e.g., clerical workers, manual workers).

For alcohol consumption, there were fewer participants in the exposed group who reported drinking more than recommended by the low-risk drinking guidelines (i.e., more than a total of 10 standard drinks during the previous 7 days, and/or more than two drinks in any

day during the previous 7 days, and/or drinking on more than five of the previous 7 days) than those in the unexposed group at the first follow-up survey. However, at the second follow-up, there were no differences between groups in self-reported alcohol consumption. When examining effects of exposure by gender, findings showed this effect of campaign exposure on adhering to low-risk drinking guidelines was associated with benefit in women, but not in men, at the first follow-up survey.

Finally, among people who reported exceeding drinking guidelines at baseline, campaign exposure was associated with improved knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline and risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage, similar to the campaign effects across all participants.

Researchers in this study evaluated a French mass media campaign designed to improve knowledge of alcohol-related health risks and low-risk drinking guidelines and reducing alcohol consumption. Results showed that there was an immediate effect of the campaign on improving knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline and risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage among both the general population and a subset of people who reported drinking more than recommended. There was also an immediate effect of the campaign on reducing the proportion of people who exceed low-risk drinking guidelines among the general population. However, none of these benefits remained at the second follow-up 6 months after the campaign ended.

Results also showed that campaign exposure improved knowledge of health risks and guidelines among people who reported drinking more than recommended by the guidelines. This is notable because reducing risks for people who drink in potentially harmful ways is likely to have an even greater positive impact on public health and possibly public safety as well (e.g., reduced driving while over the legal limit). At the population level, this could exert a large-scale public health impact even though the immediate effects were relatively small.

The benefits of the campaign on reduced drinking being stronger in women may be partially due to women drinking less alcohol overall than men. Thus, for women who were not already drinking within the guidelines, they may not have had to remove as many as drinks as men to meet the low-risk guidelines. This finding may also be due to women typically being more concerned about their health than men. Nonetheless, it is particularly important, given that women are more sensitive to the effects of alcohol and develop negative health consequences sooner.

Although the campaign was associated with short-term effects, its inability to produce long-term changes in alcohol consumption is consistent with other research showing the limitations of alcohol-related public health campaigns in reducing alcohol consumption over the long term. For youth specifically, the substantial amount of evidence showing that the widely popular Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) is ineffective in reducing drug use further points to the need for public health prevention and intervention to go beyond raising awareness and improving education to directly target key risk factors (e.g., teaching social and emotional skills; promoting parental monitoring and nurturance through parent-based interventions; promoting alternative behavioral strategies and a sense of community).

A mass media campaign designed to improve knowledge of alcohol-related health risks and low-risk drinking guidelines and reduce alcohol consumption had a short-term effect on these outcomes, but the effects did not last long-term. Accordingly, mass media campaigns may be helpful immediately, but in the absence of additional approaches that target risk factors at both individual and community levels on an ongoing basis, are unlikely to produce sustained behavior change.

Quatremère, G., Guignard, R., Cogordan, C., Andler, R., Gallopel‐Morvan, K., & Nguyen‐Thanh, V. (2023). Effectiveness of a French mass‐media campaign in raising knowledge of both long‐term alcohol‐related harms and low‐risk drinking guidelines, and in lowering alcohol consumption. Addiction, 118(4), 658-668. doi: 10.1111/add.16107

l

Alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of disease and disability through several potential health problems, such as hypertension and cancer. As a result, public health officials have established recommended guidelines for alcohol consumption levels to prevent such problems. For instance, in the US it is recommended that, for those who choose to drink, men limit alcohol use to 2 standard drinks or less per day and women limit alcohol use to 1 standard drink or less per day. In France, where this study took place, it is recommended that both men and women should not consume more than 10 standard drinks per week, no more than 2 standard drinks per day, and should have at least 2 alcohol-free days per week. Of note, the definition of a “standard drink” differs by country; in the US, a standard drink is defined as 14 grams of pure alcohol, while in France, it is 10 grams.

In the US, approximately 36% of people reported a heavy drinking session in the last 30 days, and in France, this percentage is 41.5%. A heavy drinking episode was defined as consuming 60 or more grams of pure alcohol, which is equivalent to 4 standard drinks in the US and 6 in France. This may be due, in part, to lack of awareness of health risks, as more than 50% of Americans are unaware that alcohol increases risk of cancer, and lack of awareness of the low-risk drinking guidelines.

Mass media campaigns may help increase the knowledge about alcohol-related health risks and drinking guidelines, reaching many people over a short time period. Researchers in this study evaluated the effectiveness of such a campaign in France. This research can help shed light on whether mass media campaigns intended to improve public health make a difference in the public’s knowledge and health behaviors.

This study evaluated a mass media campaign in France by comparing recollections of having been exposed to the campaign or not, that aimed to improve the public’s knowledge of low-risk drinking guidelines and alcohol-related health risks and thereby reduce alcohol consumption. The campaign was broadcast for 1 month and surveys were conducted prior to the campaign, immediately after it ended, and 6 months after it ended.

The audio/visual campaign was broadcast through popular TV and social media advertisements. The campaign’s primary advertisement showed actors in different situations with a voice-over saying that alcohol does not have to end with a disaster (e.g., a car accident or a fight) and then explaining that more 2 drinks a day increases risk of a brain hemorrhage, cancer, and hypertension. It ended with the campaign slogan: “For your health, no more than two alcohol drinks per day. And not every day.” In addition to this advertisement, advertisements and videos were also broadcast online and in health facilities, interviews with addiction experts were broadcast on national radio stations, and posters were hung in health care settings.

During the first follow up survey (right after the campaign ended), the researchers also assessed exposure to the campaign with self-reported and assisted campaign recall. Each campaign item (i.e., advertisements, radio interviews, posters, etc.) was shown in random order and participants were asked if they remember having seen or heard each one. If yes, they were considered to be in the “exposed” group.

To be eligible for the study, participants had to have reported drinking alcohol in the last 12 months, as assessed via a screening question that was adapted from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) questionnaire. The research team recruited a sample of 4002 people between the ages of 18 and 75 to complete an online survey. The sample was nationally representative, but was limited to those with access to the Internet. Of the 4002 participants who responded to the baseline survey, 3005 completed the first follow up survey immediately after the campaign ended, and 2538 completed the second follow up survey 6-months after the campaign ended. These people were included in the analyses. Women (vs. men) and younger individuals (vs. older) were more likely to miss a follow-up assessment.

At the first follow-up survey, they also recruited a new sample of 501 participants to test whether any potential benefit of the campaign was attributable to exposure to the campaign itself and not a combination of the campaign and initial questionnaires that primed individuals to pay more attention to the campaign. They hypothesized that if there are differences between the 2 groups at the first follow up immediately following the campaign, then there is likely a priming effect accounting for at least some of the campaign benefits.

Differences between exposed and unexposed groups.

Among all participants, 74.5% reported recognizing at least one campaign item (i.e., the exposed group), with the majority (67%) recognizing the TV ad.

Participants in the exposed group were older than those in the unexposed group, with 74.5% of exposed participants being older than 35 years, compared to 67.7% of unexposed participants. Participants in the exposed group also had lower levels of education, with 27.7% having less than an upper secondary school certificate (equivalent to a high school diploma in the US), versus 21.7% in the unexposed group.

Before the campaign (i.e., baseline assessment), participants ultimately exposed to the campaign were slightly more likely to report thinking about their drinking in the previous 30 days (16.0% versus 12.4%, respectively) and to report a desire to reduce their alcohol consumption (22.7% versus 18.8%, respectively).

Campaign exposure improved short-term knowledge and reduced alcohol consumption, but for some groups more than others.

At the first follow-up survey immediately after the campaign ended, the exposed group was more likely to report knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline than the unexposed group. However, there were no differences between groups in knowledge of the ‘minimum of 2 days without alcohol a week’ guideline. At the second follow-up survey 6 months after the survey ended, there were no differences between groups for either guideline.

Also at the first follow-up survey, the exposed group was more likely to report knowledge of the risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage than the unexposed group. However, at the second follow-up, there were no differences between groups for any of the health risks. There were no differences between groups at either follow-up survey for perceived susceptibility and intention to reduce alcohol consumption in the next 30 days.

The effect of campaign exposure on alcohol-related hypertension knowledge differed by socioeconomic status, however. There was improved knowledge of risk for alcohol-related hypertension risk at the first follow-up survey among those in high socio-professional categories (e.g., managers, farmers, retailers, business owners), but not among those in low socio-professional categories (e.g., clerical workers, manual workers).

For alcohol consumption, there were fewer participants in the exposed group who reported drinking more than recommended by the low-risk drinking guidelines (i.e., more than a total of 10 standard drinks during the previous 7 days, and/or more than two drinks in any

day during the previous 7 days, and/or drinking on more than five of the previous 7 days) than those in the unexposed group at the first follow-up survey. However, at the second follow-up, there were no differences between groups in self-reported alcohol consumption. When examining effects of exposure by gender, findings showed this effect of campaign exposure on adhering to low-risk drinking guidelines was associated with benefit in women, but not in men, at the first follow-up survey.

Finally, among people who reported exceeding drinking guidelines at baseline, campaign exposure was associated with improved knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline and risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage, similar to the campaign effects across all participants.

Researchers in this study evaluated a French mass media campaign designed to improve knowledge of alcohol-related health risks and low-risk drinking guidelines and reducing alcohol consumption. Results showed that there was an immediate effect of the campaign on improving knowledge of the ‘maximum two drinks a day’ guideline and risks for hypertension and brain hemorrhage among both the general population and a subset of people who reported drinking more than recommended. There was also an immediate effect of the campaign on reducing the proportion of people who exceed low-risk drinking guidelines among the general population. However, none of these benefits remained at the second follow-up 6 months after the campaign ended.

Results also showed that campaign exposure improved knowledge of health risks and guidelines among people who reported drinking more than recommended by the guidelines. This is notable because reducing risks for people who drink in potentially harmful ways is likely to have an even greater positive impact on public health and possibly public safety as well (e.g., reduced driving while over the legal limit). At the population level, this could exert a large-scale public health impact even though the immediate effects were relatively small.

The benefits of the campaign on reduced drinking being stronger in women may be partially due to women drinking less alcohol overall than men. Thus, for women who were not already drinking within the guidelines, they may not have had to remove as many as drinks as men to meet the low-risk guidelines. This finding may also be due to women typically being more concerned about their health than men. Nonetheless, it is particularly important, given that women are more sensitive to the effects of alcohol and develop negative health consequences sooner.

Although the campaign was associated with short-term effects, its inability to produce long-term changes in alcohol consumption is consistent with other research showing the limitations of alcohol-related public health campaigns in reducing alcohol consumption over the long term. For youth specifically, the substantial amount of evidence showing that the widely popular Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) is ineffective in reducing drug use further points to the need for public health prevention and intervention to go beyond raising awareness and improving education to directly target key risk factors (e.g., teaching social and emotional skills; promoting parental monitoring and nurturance through parent-based interventions; promoting alternative behavioral strategies and a sense of community).

A mass media campaign designed to improve knowledge of alcohol-related health risks and low-risk drinking guidelines and reduce alcohol consumption had a short-term effect on these outcomes, but the effects did not last long-term. Accordingly, mass media campaigns may be helpful immediately, but in the absence of additional approaches that target risk factors at both individual and community levels on an ongoing basis, are unlikely to produce sustained behavior change.

Quatremère, G., Guignard, R., Cogordan, C., Andler, R., Gallopel‐Morvan, K., & Nguyen‐Thanh, V. (2023). Effectiveness of a French mass‐media campaign in raising knowledge of both long‐term alcohol‐related harms and low‐risk drinking guidelines, and in lowering alcohol consumption. Addiction, 118(4), 658-668. doi: 10.1111/add.16107