While medications show promise, those effective for amphetamine use disorder are few and far between

There are currently no FDA-approved medications for methamphetamine or amphetamine use disorders, yet there are some promising medication candidates. This study reviews existing evidence for several medication classes and offers future directions.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In the background of the ongoing opioid crisis, rates of methamphetamine/amphetamine (henceforth “amphetamine”) use and associated overdose deaths are rising. However, unlike opioid use disorder, there are no FDA-approved medications for amphetamine use disorder. Numerous medications have been tested to see whether they can help reduce amphetamine use and improve study/treatment retention and recovery. However, the results of these studies are varied, and the methods used to test these treatments have limitations. Fortunately, researchers continue to work toward developing and evaluating medications to help treat this disorder. The authors of the current study reviewed dozens of articles on the topic to provide a summary of 1) medications studied to date, 2) the effectiveness and strength of the evidence supporting their use in treatment, and 3) recommendations for where we should go from here.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

For this study, the authors conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adults with amphetamine use disorder that tested medications against other medications, placebo, or psychotherapy. The initial search included 5,936 articles. They identified 369 relevant articles for full review, and 18 of these articles satisfied eligibility criteria. These 18 articles represented findings from 34 clinical trials, with samples ranging from 19 to 229 patients. Once reviewed, the authors performed a meta-analysis. This involved combining the results of the 34 trials reviewed to derive an overall summary estimate of the effectiveness of each medication across studies.

For this study, the authors were interested in research comparing medications to 1) other medications, 2) placebo treatments, or 3) psychotherapy for adults (i.e., 18+ years) with amphetamine use disorder. The authors excluded articles that included individuals with psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder, as well as studies that did not perform urinary analysis at least once per week. Thus, studies relying on self-report data (e.g., participants report how much they used amphetamines) were excluded from their review. Their primary outcomes were sustained abstinence (measured by urinalysis), overall amphetamine use, treatment retention, and adverse effects.

In addition to evaluating the outcomes of the studies they found, the authors also considered the strength of the evidence each study provided and rated them accordingly (e.g., “low strength,” “moderate strength”). An example of “low strength” research would include inconsistent findings, research that does not test intervention effects on amphetamine use directly, or research with low internal validity (i.e., study constructed in a way where causal inferences are limited due to the design of the study). In contrast, “moderate” or “high strength” studies would indicate moderate-high consistency across studies, direct observation of effects on amphetamine use-related outcomes, and internal validity. The researchers also took into account any risk of publication bias by assessing the likelihood that studies finding no effects for the medication were withheld from publication. They evaluated this by considering, among other things, the number of clinical trials documented on a research study registration website (ClinicalTrials.gov) to estimate how many studies should have been published vs. the number that have actually been published.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

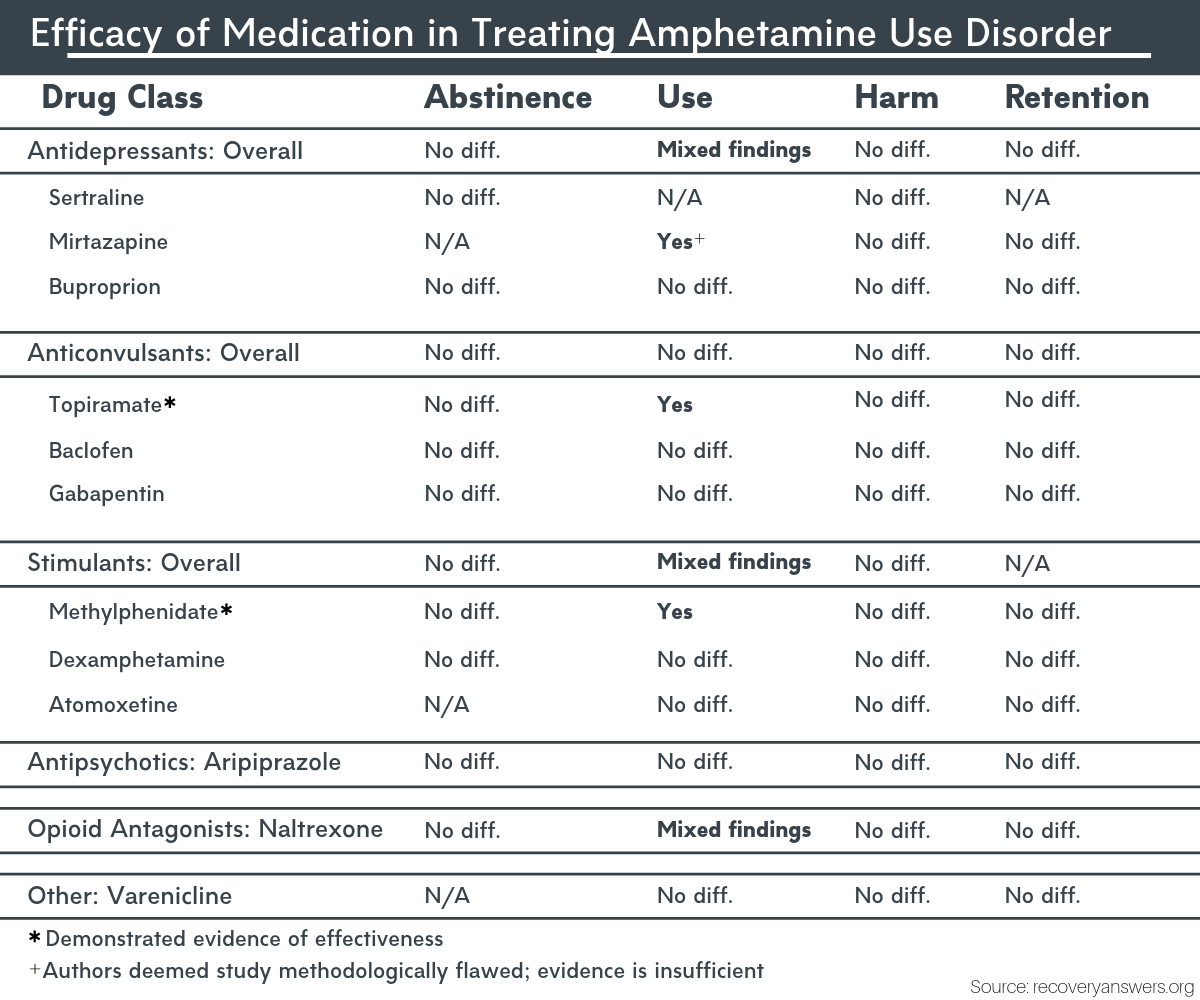

The review yielded studies that tested medications within the following six medication classes: Antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, opioid antagonists, stimulant medications, and “other”. By and large, the results of these studies suggest little, no, or “insufficient” evidence that these tested, existing medications are useful in treating amphetamine use disorder, with two possible exceptions: Methylphenidate (sometimes known by the brand name Ritalin) – a stimulant medication – and topiramate (sometimes known by the brand name Topamax) – an anticonvulsant medication – showed promise in their ability to reduce amphetamine use.

In two out of five reviewed studies, methylphenidate was shown to reduce amphetamine use (e.g., proportion of negative urine results was 32.7% vs. 18% in the placebo group). In another study, topiramate was also found to produce greater reductions in amphetamine use (e.g., over 25% reduction in amphetamine use 6-12 weeks after baseline assessment). In summary, the results suggest that psychostimulant medication such as methylphenidate, and anticonvulsant medication such as topiramate, may help individuals reduce their use of amphetamine.

The authors deemed the evidence presented regarding other medications either non-significant or “insufficient” to support a conclusion at this time. On the other hand, the authors conclude that there is “low” to “moderate” evidence to support that antidepressant, antipsychotic, and opioid antagonist medications are not effective at increasing treatment retention or reducing amphetamine use or use-related harm.

- Antidepressants

-

9 clinical trials evaluated the use of bupropion (common brand name: Welbutrin), sertraline (e.g., Zoloft), and mirtazapine (e.g., Remeron). The authors found “moderate strength” evidence that this class of drugs did not have a significant effect on rates of amphetamine use, or treatment/study retention. Overall, data were deemed “insufficient” to conclude that antidepressants are effective, though one study did find support that mirtazapine may reduce amphetamine use.

- Antipsychotics

-

2 clinical trials evaluated the use of aripiprazole (e.g., Abilify). The authors determined that these studies provided “low strength” and “insufficient” evidence that this class of drugs is helpful in reducing amphetamine use and found some evidence of increased harm as a result of use.

- Anticonvulsants

-

2 clinical trials evaluated topiramate (e.g., Topamax), baclofen (e.g., Lioresol), and gabapentin (e.g., Neurontin). There was no evidence of improved outcomes among those treated with gabapentin and baclofen, though individuals treated with topiramate were more likely to reduce amphetamine use between 6- and 12-weeks following baseline assessment.

- Psychostimulants

-

11 clinical trials evaluated methylphenidate (e.g., Ritalin), modafinil (e.g., Provigil), and atomoxetine (e.g., Strattera), and dexamphetamine (e.g., Adderall). The authors determined there was “low strength” evidence that these medications do not produce improved outcomes. However, 2 out of 5 clinical trials testing methylphenidate specifically found this drug to help reduce amphetamine use.

- Opioid antagonists

-

4 clinical trials evaluated naltrexone (e.g., Vivitrol). The authors determined there was “low strength” evidence that naltrexone does not reduce amphetamine use, use-related harm, or study retention.

- Other: Varenicline, citocoline, ondansetron, prometa, riluzole

-

5 additional trials evaluated the use of alternative medications. All except one study found no evidence of reduced amphetamine use, harm, or increased study retention. One study on riluzole (e.g., Rilutek) found evidence of reduced amphetamine use, but no effect on retention and evidence of greater harm. The authors of this review found a high level of bias that may undermine these findings.

Figure 1. Comparison of medication efficacy for treating amphetamine use disorder.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study is important because it evaluates and summarizes existing studies on the effects of medications to treat amphetamine use disorder. Compared to previous research, this study includes a broader range of medications, as well as harms related to use and treatment retention outcomes. The most noteworthy implications of this study are that many researchers have tested medications to treat amphetamine use disorder, with most studies showing little or no improvement. However, two medications, methylphenidate and topiramate, may help individuals reduce amphetamine use. This is significant in the absence of existing FDA-approved medications; however, additional research is needed. In the meantime, treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management, which are psychotherapeutic interventions shown to be both effective and cost-effective, are currently the front-line treatment recommendations for amphetamine use disorder. Involvement in mutual-help organizations such as Narcotics Anonymous or Crystal Meth Anonymous might also be useful. For example, research also shows that efforts to increase mutual-help group attendance can lead to improved outcomes among individuals with amphetamine use disorder.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The authors omitted studies not published in English from their review.

- In this study, “abstinence” was defined as abstaining from amphetamine use for 3 or more weeks; future research would benefit from examining abstinence periods of longer duration.

- The authors excluded articles that relied on participant/patient self-report. This may have resulted in the exclusion of many relevant articles that could have informed readers about the scope of medications used to treat amphetamine use disorder and their effectiveness.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: There are currently no FDA-approved medications for amphetamine use disorder, and it is too soon to recommend any of the above-mentioned treatments as front-line treatments for amphetamine use disorder. Although additional research is needed, of the medications reviewed in the current study, methylphenidate and topiramate demonstrated the most promise and may help reduce amphetamine use. Although other medications such as antidepressants were not found to be effective in reducing amphetamine use, use of pharmacological intervention may still help address other symptoms related to amphetamine use, such as anxiety and depression. Alternatively, you can speak with your provider about treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management, which are psychotherapeutic interventions shown to be effective and are currently the front-line treatment recommendations for amphetamine use disorder. Research shows that involvement of friends and family in treatments like Contingency Management (e.g., rewarding negative urine screens and recovery milestones) can improve outcomes. Other recommendations include combining these approaches with education about the nature and effects of amphetamine use disorder, involvement in mutual-help organizations such as Narcotics Anonymous or Crystal Meth Anonymous, and mobile applications; however, most apps have not been evaluated formally.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Though the data from this review do not provide strong support for pharmacological treatment for amphetamine use disorder, all of the medications evaluated have utility with respect to managing other symptoms related to substance use disorder and recovery (e.g., depression, anxiety, psychotic symptoms). Fortunately, there are multiple pathways to recovery. As such, clinicians are also encouraged to recommend psychotherapeutic and behavioral interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management, or combining these approaches with pharmacological intervention to improve outcomes. In addition, providers are encouraged to carefully consider medication choice and to make clear to patients the risks and potential benefits of these medications to reduce amphetamine use.

- For scientists: This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that medications are generally ineffective in treating amphetamine use disorder, though methylphenidate and topiramate demonstrated some promise. Many of the studies reviewed offered incomplete information about study procedures, used different outcome measures, and/or small samples. The implication here is that more research is needed. Lastly, though methylphenidate and topiramate have some emerging evidence, much more research is needed to identify precise mechanisms of action, optimal dose and other drug combinations, and to perform subgroup comparisons (e.g., effectiveness for men vs. women).

- For policy makers: In the background of alcohol use disorder and the opioid epidemic, other potentially harmful drugs such as amphetamine and methamphetamine receive relatively little public and research attention. It is also true that while substances such as alcohol and opioids currently have FDA-approved medications used regularly to treat alcohol and opioid use disorders, no medications are currently approved to treat amphetamine use disorder. At the same time, there are several efficacious and cost-effective psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management, that would benefit from greater dissemination. Given the rise in amphetamine use disorder, and related overdose deaths in recent years, more funding and media attention specifically dedicated to this substance use disorder are needed to properly intervene and prevent further escalation of amphetamine use nationally.

CITATIONS

Chan, B., Freeman, M., Kondo, K., Ayers, C., Montgomery, J., Paynter, R., & Kansagara, D. (2019). Pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine/amphetamine use disorder – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, (ePub ahead of print). doi: 10.1111/add.14755