Does cannabis use disorder treatment also improve depressive symptoms in adolescents?

Adolescents with cannabis use disorder often also experience depressive symptoms. Both cannabis use and depressive symptoms tend to abate during addiction treatment and recovery, but little is known about the dynamic pattern of change between substance use and depressive symptoms while youth are engaged in addiction treatment. This study examined patterns of depression symptoms and cannabis use over a year among adolescents receiving treatment for a cannabis use disorder to further inform clinical practice and research.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Evidence suggests that 20-30% of adolescents with cannabis use disorder also experience depressive symptoms. A variety of theories suggest different pathways for this relationship including 1) that youth “self-medicate” depressive symptoms with cannabis use, resulting in the substance use disorder, 2) that cannabis use causes depressive symptoms, 3) that there are multiple factors involved in, and underlying, both the depression and cannabis use, or 4) that neither experience/behavior is related, but co-occur anyway.

These theories suggest that during the course of treatment for a cannabis use disorder, depression symptoms could worsen as a result of removing the marijuana use as a form of pharmacological coping, or alternatively, improve as a result of improving mood due to long-term reduction or abstinence of cannabis use. As well, there is the possibility that depression could interfere with treatment, rendering it less effective. Arias and colleagues aimed to determine if and how depression symptoms and cannabis use changed during a year of treatment by analyzing data among adolescents who were engaged in one of several evidence-based treatments for cannabis use disorder. With this empirically-based information, clinicians could better assist adolescents with cannabis use disorder who also present with symptoms of depression.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary analysis of data collected in the Cannabis Youth Treatment study, a multisite randomized clinical trial that compared the effectiveness of five evidence-based cannabis use disorder treatments for adolescents. It is important to note that these were treatments designed to address cannabis use disorder and were not adapted to address co-occurring mental health issues. Study treatments lasted until week 15 and youth were followed every 3 months after beginning treatment (i.e., 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-ups). In this study, data were analyzed to examine how cannabis use and depressive symptoms changed during the year following treatment.

Participants completed the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs at the study entry and the follow-up time points – a standardized multidimensional measure used to collect days of cannabis use and depression symptoms, as well as a variety of other things. To help corroborate self-reported abstinence or days of cannabis use, participants also provided urine samples that screened for the presence of different substances including cannabis. The primary outcomes were measured as days of cannabis use in the past 90 days (e.g., since the last follow-up), as well as the number of depression symptoms, and a diagnosis of major depressive disorder was calculated using the number of depressive symptoms (i.e., if four or more were reported, participants were diagnosed with major depressive disorder).

To understand the dynamic interplay of cannabis use and depression symptoms over the year-long follow-up, the researchers used a series of sophisticated analyses to test if the level of one variable, i.e., the degree of cannabis use, was a leading indicator of change in another factor, i.e., the degree of depressive symptoms over time.

The study population was 600 adolescents, ages 12-18 years who were diagnosed with a cannabis use disorder and had used cannabis once in the 90 days before intake. The sample was mostly male (83%), white (61%), and on average almost 16 years old. A majority (62%) had been involved with the criminal justice system. The follow-up rate of participants was very high (>90%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Most youth reported comorbid mental health issues before entering cannabis use disorder treatment.

The majority (70%) of the youth participants reported at least one depressive symptom and 18% reported enough criteria for a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Half of the participants currently also had a conduct disorder.

Depression and cannabis use decreased during the 12-month study.

Prior to treatment adolescents reported using cannabis on average 36 out of the 90 previous days, but reported 23 or fewer days after treatment; similarly, they reported 1.8 out of 6 depression symptoms on average at baseline, but 1.4 or fewer symptoms after treatment.

Figure 1. Error bars are provided for each point on the chart, indicating the accuracy of the mean. Smaller error bars indicate greater chance of the mean being correct.

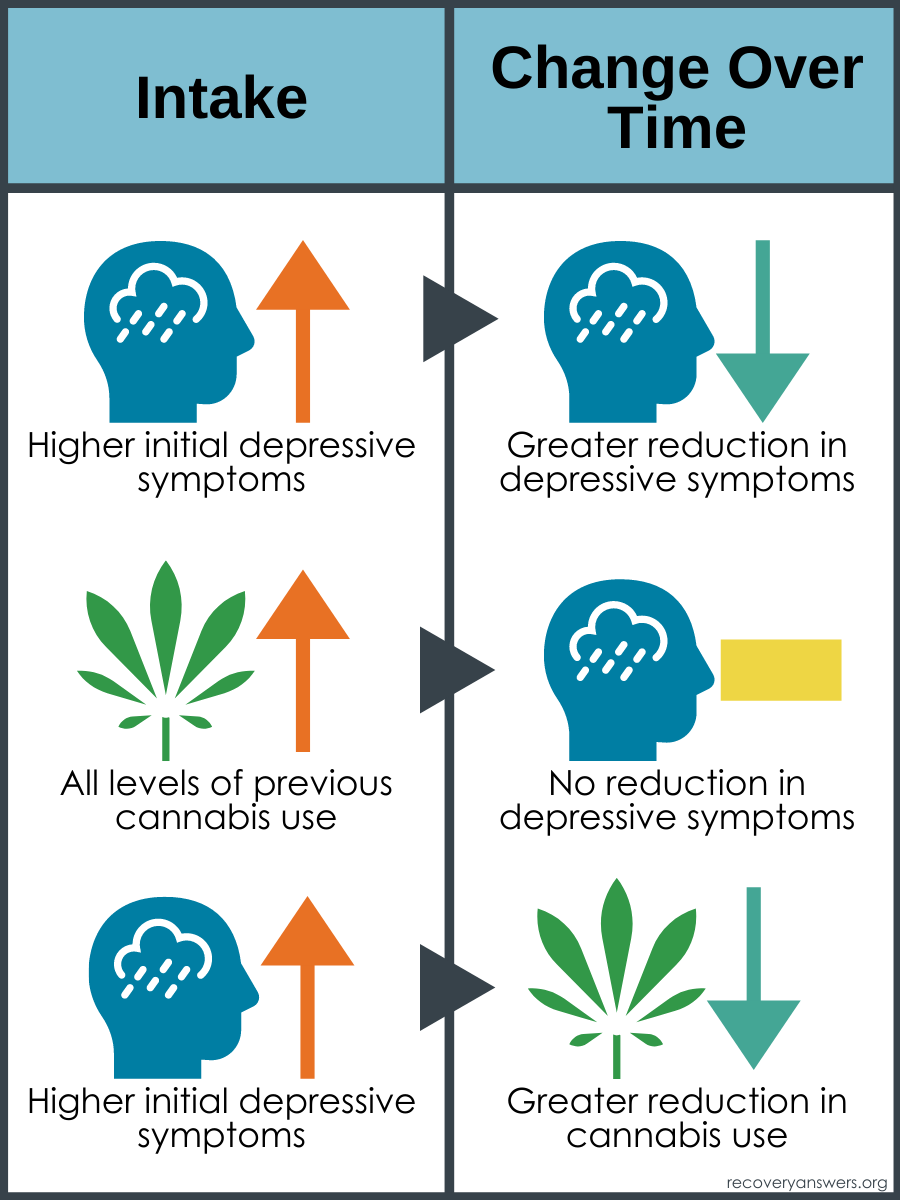

Higher levels of depression predicted a greater drop in both depressive symptoms and in cannabis use.

Change in depressive symptoms was predicted by previous depressive symptoms such that those with higher levels experienced a greater reduction in symptoms at later follow-ups. Levels of previous cannabis use were not related to reductions in depressive symptoms, yet those with higher initial levels of depression had greater reductions in cannabis use.

Figure 2.

Reducing cannabis use was significantly associated with lower depressive symptoms.

Participants who reduced their cannabis use during the 12-months of the study were more likely to report fewer depressive symptoms. Improvements to both depressive symptoms and cannabis use occurred early in the study and further improved during the course of the study, even after treatment was completed, regardless of which of the 5 clinical interventions participants received.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In this study, the researchers found that youth who attend treatment for cannabis use disorder are highly likely to experience depressive symptoms. As well, this study found that depressive symptoms were not linked to barriers to engaging and completing treatment, suggesting that youth with cannabis use disorder and depression can successfully recover from cannabis use disorder. Furthermore, evidence-based cannabis use disorder treatment reduced both cannabis use and depressive symptoms among youth, a finding that is consistent with other research demonstrating reductions in mental health symptoms in response to substance use disorder treatment.

It is possible that some of these findings are due to the fact that substance use disorder treatment often must also address mental health; i.e., these interventions focus in part on internal triggers, such as negative affect or depressive symptoms for substance use. Supporting this argument is the finding that reductions in cannabis use and depression did not appear to vary by type of treatment. Yet, these outcomes did vary by youth characteristics; that is, reduction in use and depressive symptoms were more likely among youth with higher initial severity of cannabis use and/or depression. It is possible that these more severely affected youth were engaged in additional supports to address both issues and thus experienced greater change; future research should address exact mechanisms leading to these group differences by severity. It is also possible that previous cannabis use produced greater levels of depression symptoms through changes in neurochemistry caused by the psychoactive ingredients in cannabis and that as individuals abstained or reduced cannabis use, their depression improved.

Given the high incidence of depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder in this sample, it is important to ensure that youth are screened for depressive symptoms when entering cannabis use disorder treatment. Creating stronger linkages between cannabis use disorder treatment and depression treatment might also produce more positive results among adolescents; furthermore, research indicates that centers that address both are of higher quality and that their clients experience better outcomes, suggesting that systematically incorporating both in one center may be more effective for youth overall.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The study only compared youth in different empirically supported treatments and did not have a comparable group who did not experience treatment (control group); thus, it is not clear how much of the effects could be a result of engaging in effective treatment versus simply dropping from a more extreme level of symptoms to an average level of depression (aka regression to the mean).

- This study involved youth in a rigorous and funded clinical trial; treatments were state-of-the-art and clinicians received intensive training and supervision. As a result, it is not clear whether the benefits observed among participants in this sample would occur in real-world settings under different resource constraints.

- These findings may only be relevant for primarily white males as they comprised the majority of the population in this study; generalizations to females or other racial/ethnic groups may or may not be appropriate.

- Although the authors examined several important factors such as criminal justice involvement and number of parents in the household, there may be other factors driving the successful reduction of cannabis use and depression that were important but not explored.

- Over a third of the sample also had an alcohol use disorder indicating they used alcohol in addition to cannabis use. This comorbid substance use could have influenced their engagement in the treatment process or affected their experience of depressive symptoms (e.g., perhaps by use of alcohol instead of marijuana to cope), yet this variable was not examined in the present study.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: In this study, researchers used data from a multisite randomized clinical trial to examine changes in both depression symptoms and cannabis use among adolescents with cannabis use disorder over a 12-month period. They found that youth receiving these cannabis use disorder treatments reduced their cannabis use and depressive symptoms. Of note, these youth with cannabis use disorder were also highly likely to report depressive symptoms. Recovery is a complex process which requires a variety of both internal and external supports – recovery capital – and so, ensuring youth are screened for depression or other mental health issues when entering treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorders may provide them with access to necessary services sooner, and may also help improve their recovery efforts. When seeking treatment supports, it may be necessary to explore treatment options that offer mental health services in addition to substance use as research has suggested that centers that do both are of higher quality and that their clients experience better outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: In this study, researchers used data from a multisite randomized clinical trial to examine changes in both depression symptoms and cannabis use among adolescents with cannabis use disorder over a 12-month period. They found that youth receiving these cannabis use disorder treatments reduced their cannabis use and depressive symptoms; all the treatments were similarly effective. Of note, these youth with cannabis use disorder were also highly likely to report depressive symptoms. Recovery is a complex process which requires a variety of both internal and external supports – recovery capital – and so, ensuring youth are screened for depression or other mental health issues when entering treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorders may provide them with access to necessary services sooner, and may also help improve their recovery efforts. Treatment professionals may also need to be aware of potential stigma surrounding mental health issues and have conversations with youth and their families to advocate for using these services. As well, providing clear linkages to further mental health resources will improve access to screening and treatment for youth with comorbid conditions and could also improve recovery outcomes: research has suggested that centers that do both are of higher quality and that their clients experience better outcomes.

- For scientists: In this study, researchers used data from a multisite randomized clinical trial to examine changes in both depression symptoms and cannabis use among adolescents with cannabis use disorder over a 12-month period. They found that youth receiving these cannabis use disorder treatments reduced their cannabis use and depressive symptoms; all the treatments were similarly effective. These youth with cannabis use disorder were also highly likely to report depressive symptoms and those with higher levels of depressive symptoms experienced greater reductions in depressive symptoms and in cannabis use during the course of the study. Recovery is a complex process that requires a variety of both internal and external supports – recovery capital – and so, future research that examines how internal resources or barriers related to mental health interact with the treatment and recovery experience is necessary to further elucidate these processes. Future questions include addressing whether different types of mental health diagnoses may influence engagement and retention in services as well as whether improvements in these symptoms co-occur with reduction in substance use. As well, future research should address the opposite scenario encountered here; that is, whether adolescents who attend treatment primarily for their depression but also have cannabis use, reduce their cannabis use in addition to reducing feelings of depression. Finally, engagement in other recovery supports, such as 12-step meetings or alternative peer groups, during the post-treatment follow-up period could be examined for their role in continued recovery success on both mental health and substance use outcomes.

- For policy makers: In this study, researchers used data from a multisite randomized clinical trial to examine changes in both depression symptoms and cannabis use among adolescents with cannabis use disorder over a 12-month period. They found that youth receiving these cannabis use disorder treatments reduced their cannabis use and depressive symptoms; all the treatments were similarly effective. Of note, these youth with cannabis use disorder were also highly likely to report depressive symptoms. Recovery is a complex process which requires a variety of both internal and external supports – recovery capital – and so, ensuring youth are screened for depression or other mental health issues when entering treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorders may provide them with access to necessary services sooner, and may also help improve their recovery efforts. Ensuring that the treatment and insurance system increases access to additional and necessary mental health resources for these youth is likely to improve recovery outcomes and provide substantial savings to the health care system.

CITATIONS

Arias, A. J., Hammond, C. J., Burleson, J. A., Kaminer, Y., Feinn, R., Curry, J. F., & Dennis, M. L. (2020). Temporal dynamics of the relationship between change in depressive symptoms and cannabis use in adolescents receiving psychosocial treatment for cannabis use disorder. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 117, 108087.