Does Injectable Naltrexone Reduce Opioid Relapse Following Incarceration? A Pilot Study

Since relapse is common among inmates with opioid use disorder following release from the criminal justice system, evidence-based treatments could be important tools that help break the cycle of re-incarceration and relapse.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

While some jails offer methadone maintenance as the standard of care, alternatives should be available to those who are uninterested in agonist therapy or have had difficulties with it in the past. This study introduces the use of an opioid antagonist, sustained-release injectable naltrexone (i.e., Vivitrol), for relapse prevention in individuals set to be released from the criminal justice system.

Despite the potential of such interventions, most addiction treatment settings have yet to adopt these models.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Participants in this 8-week trial were randomized to receive injectable naltrexone (n = 17) or no medication treatment-as-usual (TAU; n= 17). After randomization to the treatment conditions, the research staff and participants were made aware of the treatment allocation due to the nature of administration (i.e., injection) and lack of a placebo.

Patients in the naltrexone condition were induced with a 380 mg intramuscular injection prior to their release date, and were offered a second dose post-release 4 weeks later.

All participants received brief motivational enhancement counseling and referrals to general medical, psychiatry, and addiction services. The primary outcome was post-release opioid relapse at week 4 defined as 10 or more days (out of a possible 28 days) of self-reported opioid misuse following release, or two or three positive results from the three urine samples collected during week 2, 3, and 4 assessments.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Of the 17 participants receiving injectable naltrexone, one was incarcerated indefinitely and analyses were restricted to the 33 individuals who were released as planned. Additionally, one patient required repeat induction due to a delay in prison release. Naltrexone induction occurred 6 days prior to release, on average. Two patients randomized to receive naltrexone declined treatment. Twelve (75%) participants in the naltrexone group accepted a second injection at week 4 following release.

NOTABLY FROM THE STUDY:

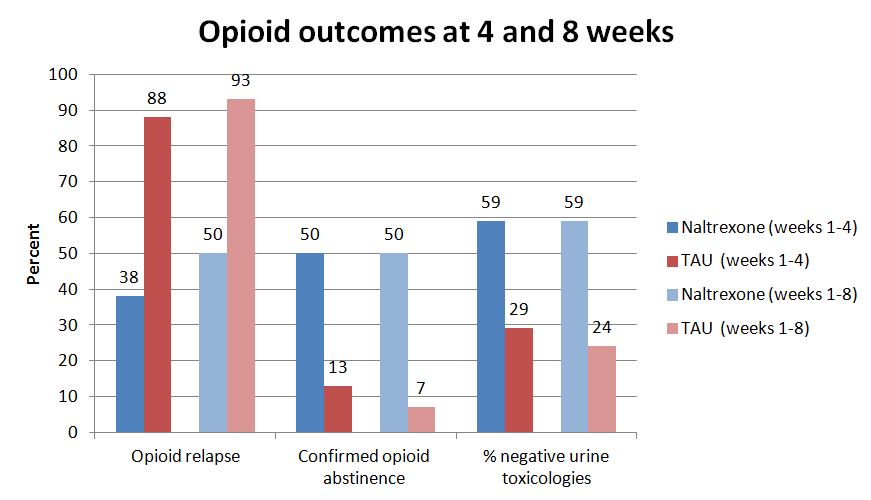

- Rates of opioid relapse at week 4 were significantly different by group with 6 (38%) of the naltrexone group and 15 (88%) of controls reporting relapse

- Re-incarceration rates were lower among the eight participants who received the additional naltrexone injection at week 4 compared to participants from the naltrexone group who received only one injection and participants from the TAU group (i.e. received no injections)

- The relapse rate was 13% for those receiving two injections versus 44% for all other participants

This study supports the potential for implementing mHealth services for office-based buprenorphine-naloxone programs as a vast majority of clinic attendees have mobile phones with text messaging capabilities.

This study demonstrates that it may be feasible to offer additional treatment options in the criminal justice system. It can be hard for individuals to re-enter society after imprisonment without the added difficulties associated with managing their addiction.

By starting the treatment and recovery process prior to release, individuals may have a better foundation and more motivation to seek treatment in their own community. Injectable naltrexone is a promising solution for reducing relapse since it provides a long window of protection and reduces the often strong influence of patient motivation to take the medication.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

Of over 2 million incarcerated individuals in the U.S., almost two thirds have a history of a substance use disorder and of these, about one quarter have an opioid use disorder (e.g., heroin).

The criminal justice system currently lacks adequate treatment for people with opioid use disorders despite returning these individuals to a risky environment (e.g., that may mean access to heroin and social groups that perpetuate use) upon release. Additionally, decreased physiological tolerance after abstinence while incarcerated may put individuals at a higher risk of overdose if they start using opioids at the same levels as prior to incarceration.

Studies have shown that use of agonist treatments, such as buprenorphine and methadone, after incarceration can decrease rates of opioid use and result in treatment outcomes that are comparable to patients not involved in the criminal justice system (see here).

However, opioid agonists and partial agonists (i.e., methadone and buprenorphine) may not be feasible options for all patients since they require frequent clinic visits, have the potential for diversion and misuse, and pose health risks when combined with other central nervous system depressants (e.g., alcohol or benzodiazepines). In addition to monthly administration (versus daily for methadone and buprenorphine) and minimal risk for misuse, injectable naltrexone can be prescribed by any physician without additional training. This pilot proof-of-concept trial helped determine feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of injectable naltrexone for opioid dependent individuals transitioning out of the criminal justice system.

If proven effective in larger trials, injectable naltrexone may be a helpful option for individuals being released from jail.

Individuals are expected to be abstinent while incarcerated so giving inmates an injection of a medication that blocks the effects of opioids (such as naltrexone) is unlikely to put them into opioid withdrawal. Monthly naltrexone injections have the potential to be more manageable and carry lower health risks for patients (than the more frequent clinic visits required of methadone, the current standard of care in most jails).

Patients ideally should also engage in ongoing counselling and other recovery support services.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- No women were deemed eligible for this study primarily due to enrollment in the jail’s methadone program, thus the sample consisted only of male participants.

- These results should be interpreted with the goals of this small, pilot trial in mind. This study sought to evaluate feasibility and effectiveness of injectable naltrexone as a proof-of-concept. While naltrexone use was associated with lower rates of relapse, the authors do not claim that injectable naltrexone is an effective treatment for this population overall. Rather, this trial is a first step in establishing evidence for its effectiveness.

NEXT STEPS

Given the results of the proof-of-concept trial, this intervention warrants more research with a larger sample size.

Future studies should also evaluate outcomes over longer periods of time and determine the potential cost-saving of this intervention. Additionally, direct comparisons between injectable naltrexone and methadone need to be carried out in this population.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Currently, injectable naltrexone is largely available for individuals with opioid use disorders while incarcerated. Medication could be a potentially helpful option to seek out after release from jail.

- For scientists: Larger trials addressing this research question are in development. Since the criminal justice system lacks options for individuals with substance use disorders, similar trials of different interventions could help determine the most feasible alternatives.

- For policy makers: Treatment options such as injectable naltrexone should be funded for use in the criminal justice system if deemed effective.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Naltrexone can be prescribed by any prescribing physician without additional training and may be a helpful option for patients who are involved with the criminal justice system.

CITATIONS

Lee, J. D., McDonald, R., Grossman, E., McNeely, J., Laska, E., Rotrosen, J., & Gourevitch, M. N. (2015). Opioid treatment at release from jail using extended-release naltrexone: a pilot proof-of-concept randomized effectiveness trial. Addiction, 110(6), 1008-1014. doi: 10.1111/add.12894