Physical activity may help people with alcohol use disorder cope with craving and unpleasant emotions. This study tested this idea out using a novel, telephone-delivered physical activity intervention with women engaged in alcohol treatment.

Physical activity may help people with alcohol use disorder cope with craving and unpleasant emotions. This study tested this idea out using a novel, telephone-delivered physical activity intervention with women engaged in alcohol treatment.

l

The benefits of physical activity on mood and well-being are well known. Some studies have also suggested that physical activity may support alcohol use disorder recovery, with a recent review suggesting benefits related to improved cognitive functioning, reduced impulsivity, improved emotion regulation, and reduced craving. Physical activity-based interventions may be especially helpful for people seeking recovery from alcohol use disorder who are experiencing common negative emotions like anxiety and depression, and the distressing discomfort of craving, or who have a goal of improving physical fitness.

The researchers behind this study thought that women may be especially inclined to engage in physical activity-based interventions for alcohol use disorder, because on average, women with alcohol use disorder tend to struggle more with anxiety and depression and are more motivated for physical fitness than men.

This study tested a novel, 12-week, telephone-delivered intervention for increasing physical activity in women participating in a partial hospital program for alcohol use disorder, comparing it to an active control group receiving telephone-delivered health education.

This was a pilot, randomized controlled, trial with 50 women in a partial hospital program (short-term, intensive outpatient treatment) for alcohol use disorder who received either a 12-week, telephone-delivered intervention for increasing physical activity, or 12 weeks of telephone-delivered health education, to determine whether physical activity is superior for reducing alcohol use lapses, alcohol craving, anxiety, depression, and stress, while increasing behavioral activation and exercise. Participants were on average 50 years of age, with 92% of the sample identifying as White, and 6% as Latina.

The study’s physical activity intervention included an initial hour-long orientation in which a study clinician provided information regarding the acute and long-term psychological and physiological benefits of increasing physical activity. Participants also received instructions about how physical activity can be utilized as a coping strategy for managing challenging emotions or alcohol cravings, as well as information on the public health guidelines for physical activity and how to determine if their physical activity is moderate intensity. The study clinician also provided instruction in the use of a Fitbit activity tracker, which participants wore for the 12-week duration of the study intervention, and helped participants brainstorm strategies for integrating physical activity into their schedules. Participants were given a starting step-count goal of 4500 steps per day with a plan for increasing 500 steps per day each week of the intervention.

Study clinicians then called participants at study weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 for a 30-minute phone session to review progress and troubleshoot barriers to achieving physical activity goals. Study clinicians also engaged participants in a brief discussion about physical activity to cope with negative emotions and cravings (weeks 1 & 2), getting and staying motivated + social support (week 4), identifying and overcoming barriers and getting back on track (weeks 6 & 8); and making plans for action and maintenance of physical activity (week 10). Participants also received brief text messages twice per week that reminded them of their current step count goal, and offered feedback and encouragement for achieving increases in their physical activity.

The participants randomized to the active control condition received the same contact time with research staff, however, the content of the material covered, and instructions differed. The active control group received 30-minute telephone sessions following the same schedule as the physical activity intervention group, however, no information about the potential benefits of physical activity were provided, nor were participants instructed to change their current levels of physical activity. Instead, participants received education in a variety of health and lifestyle topics like nutrition, sleep hygiene, and relaxation training. Participants also received text messages twice a week that provided supporting information about the topics covered in the education sessions.

Study inclusion criteria included: 1) being female, 2) ages 18–65, 3) having alcohol use disorder, 4) being currently enrolled in alcohol use disorder treatment, 5) having at least mild depressive symptoms, and 6) having low physical activity (defined as less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week for the past six months). Individuals were excluded if they had medical or psychological conditions that would make it unsafe for them to participate.

Outcomes included alcohol use (including percent days abstinent, percent of heavy drinking days, percent days of no heavy drinking, and mean drinks per day over the 12-week study period), alcohol craving, depression, positive and negative emotionality, behavioral activation (measuring avoidance/rumination, work/school impairment, and social impairment), stress, and physical activity.

Engagement with the Fitbit device was good, but study attrition was notable

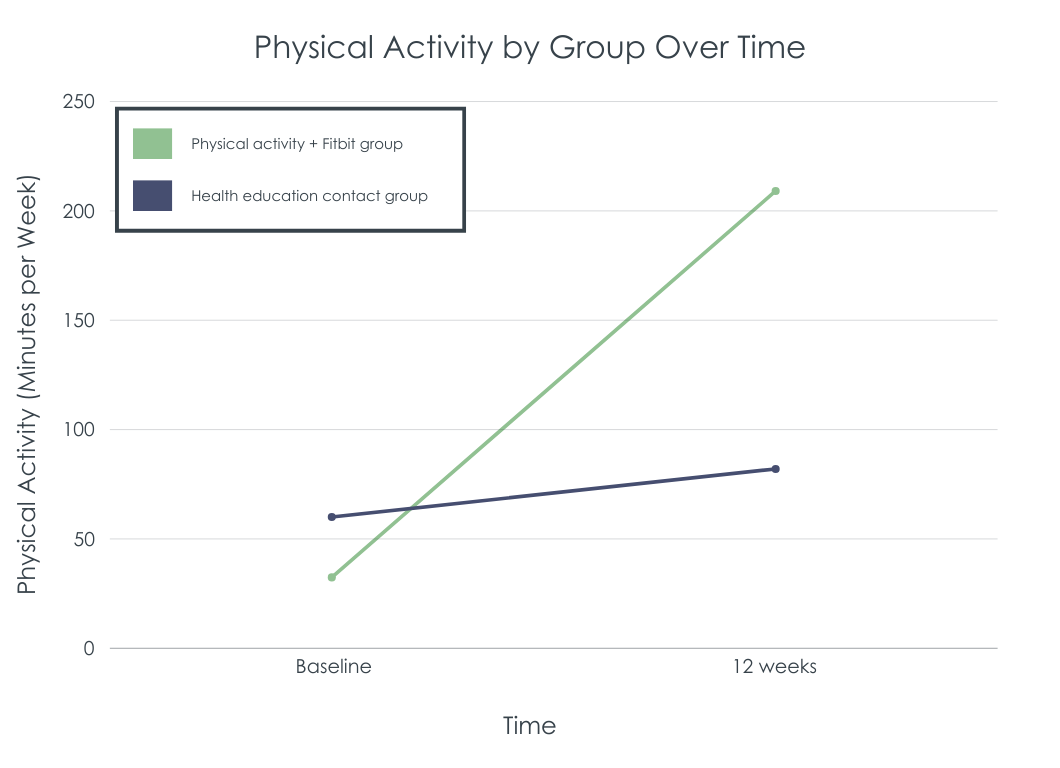

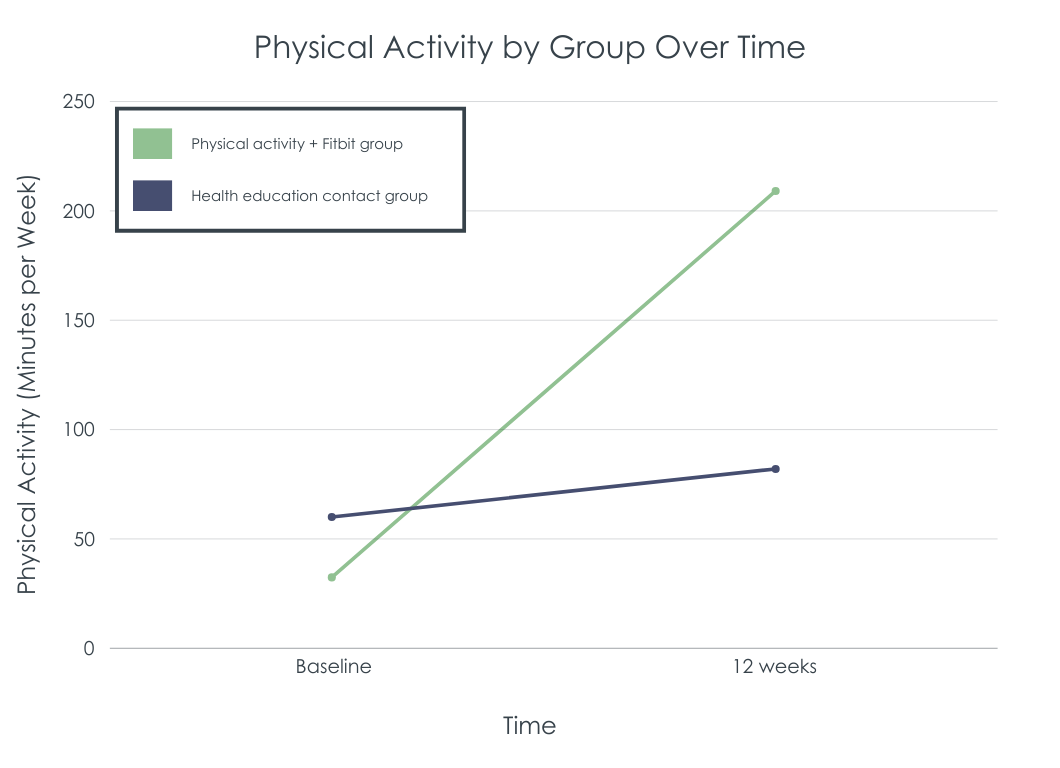

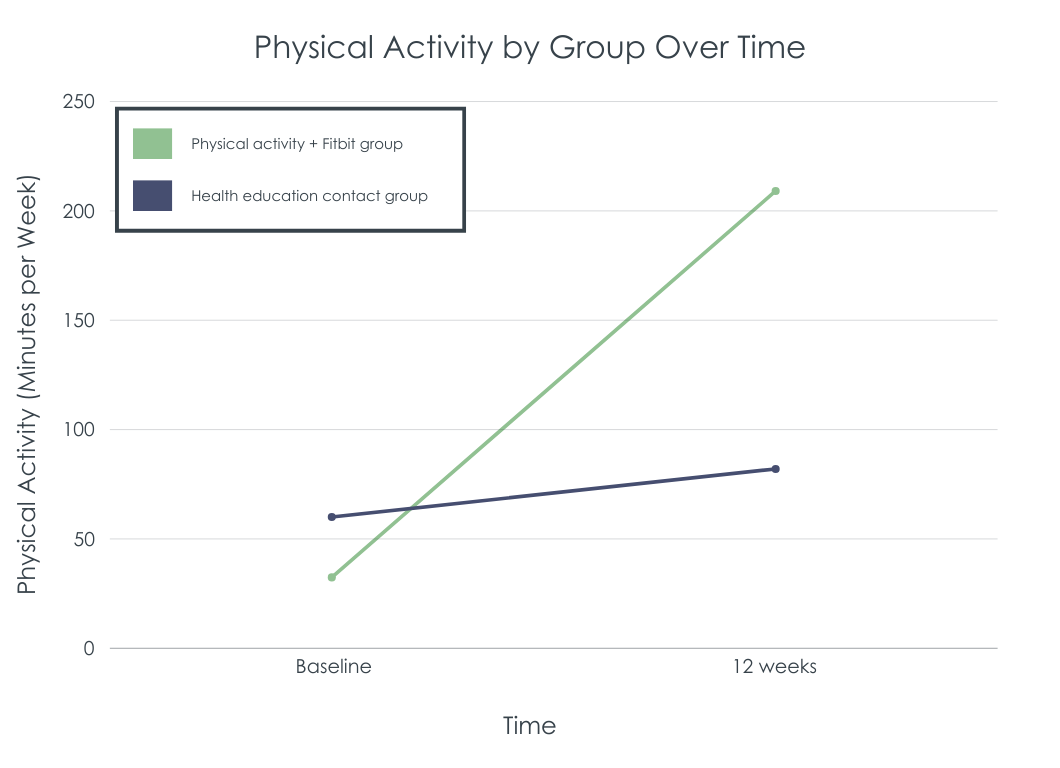

In the physical activity group, participants wore the Fitbit on 71% of days, while 80% of the sample wore the Fitbit for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the intervention, with 56% utilizing the Fitbit mobile app each day. In both groups, participants had, on average, 5 out of 6 possible phone call sessions. Among participants who wore the Fitbit for at least 6 weeks, there were significant increases in the number of steps/day (from 4,338 at baseline to 8,600 at 12-week intervention). The intervention group increased their overall physical activity more than the education comparison group (see figure below), a medium-sized effect that did not reach statistical significance in this small sample pilot study.

Drinking outcomes were similar but physical activity was associated with less alcohol craving

Drinking outcomes were similar but physical activity was associated with less alcohol craving

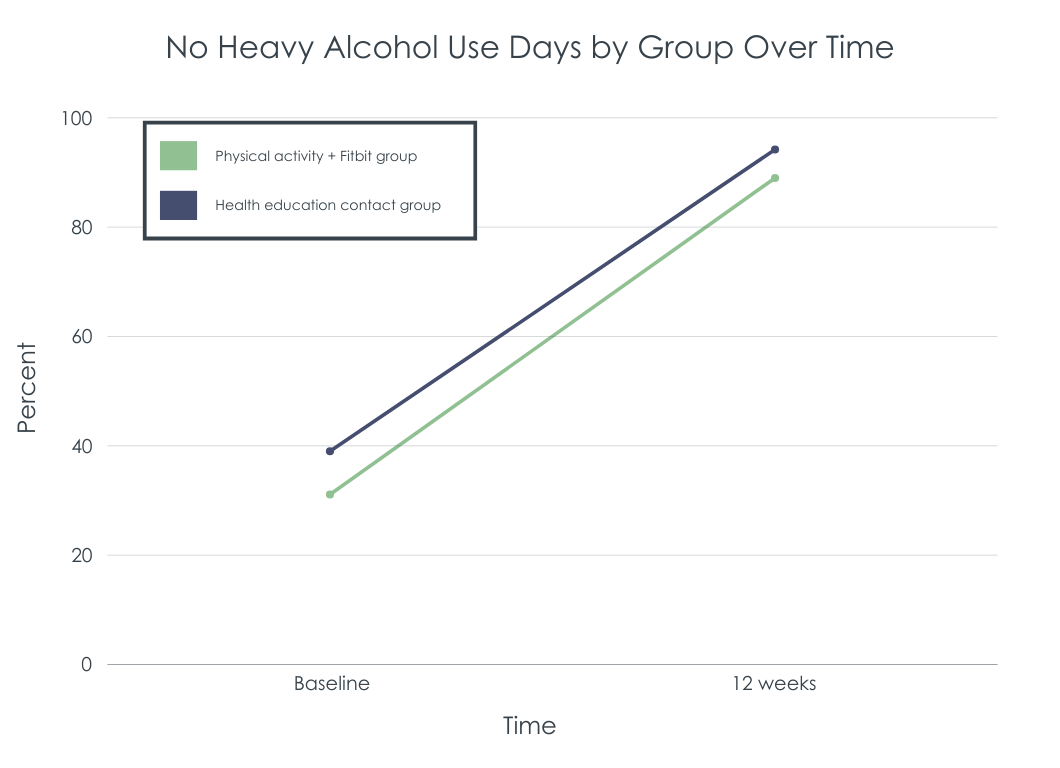

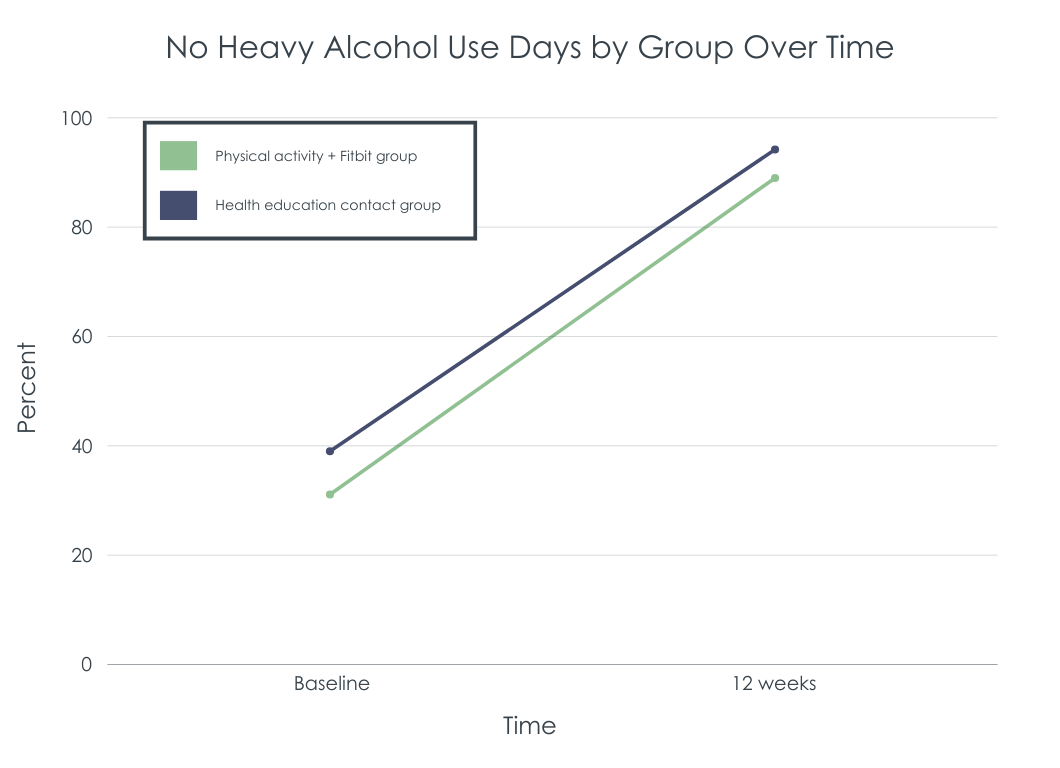

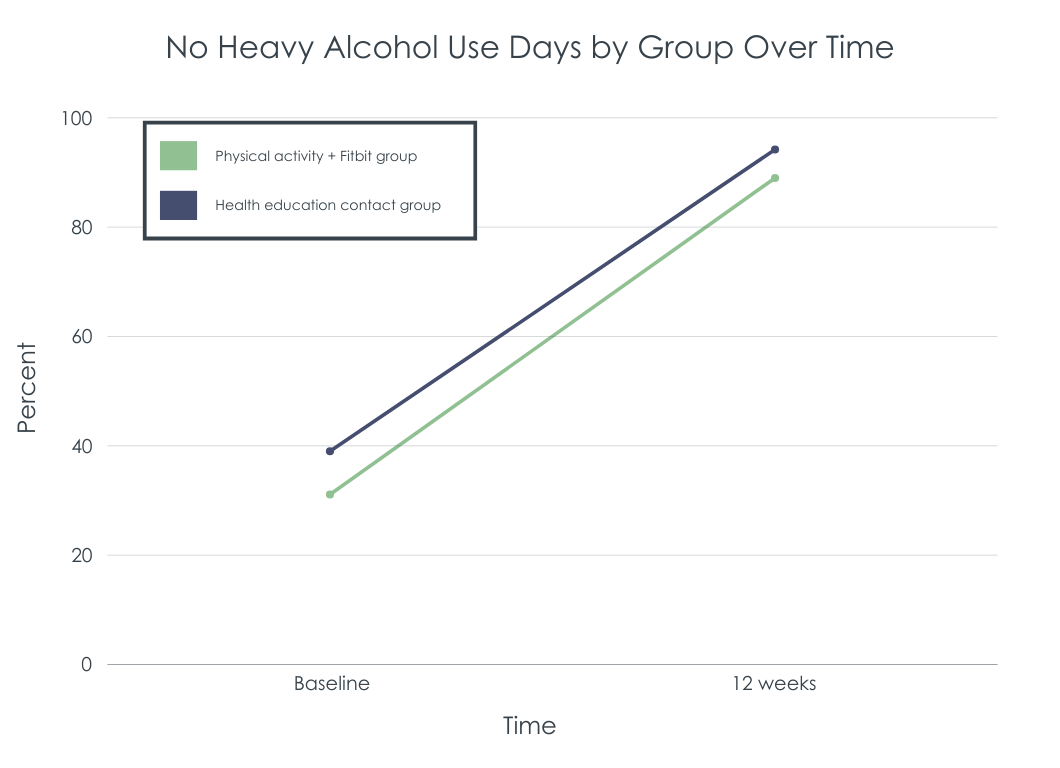

For participants who completed the end of study assessment, 56% of those in the physical activity group maintained alcohol abstinence throughout the 12-week study period, versus 33% for the control group, a difference that did not reach statistical significance likely also in part because of the study’s small sample. They also had less past-week craving with the magnitude of this effect medium in size, also a nonsignificant difference, however. On the other hand, measures of alcohol use such as percent days abstinent and percent days with no heavy drinking (see figures below), were similar between the two groups.

Physical activity was associated with better mental health outcomes

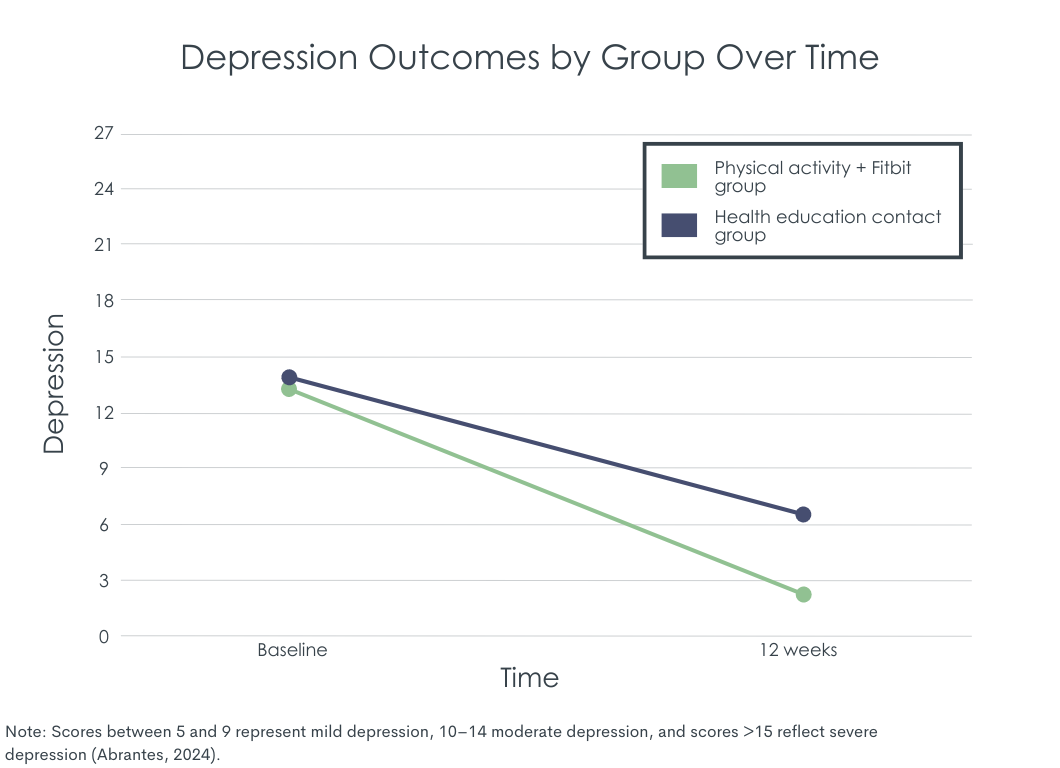

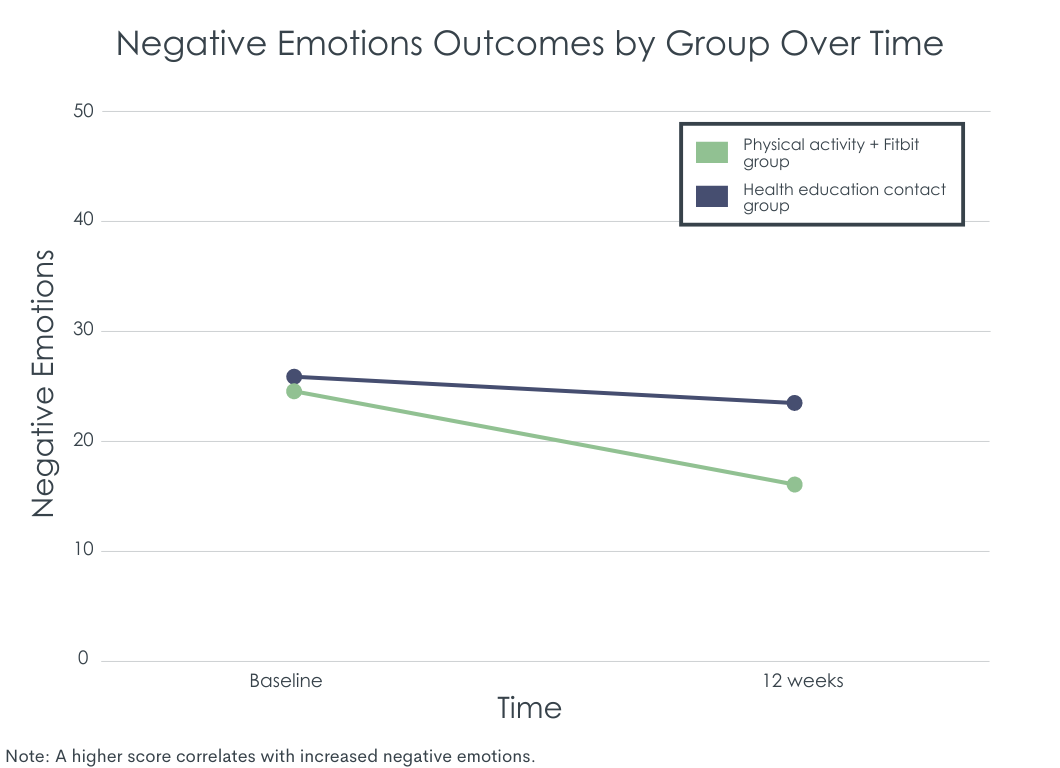

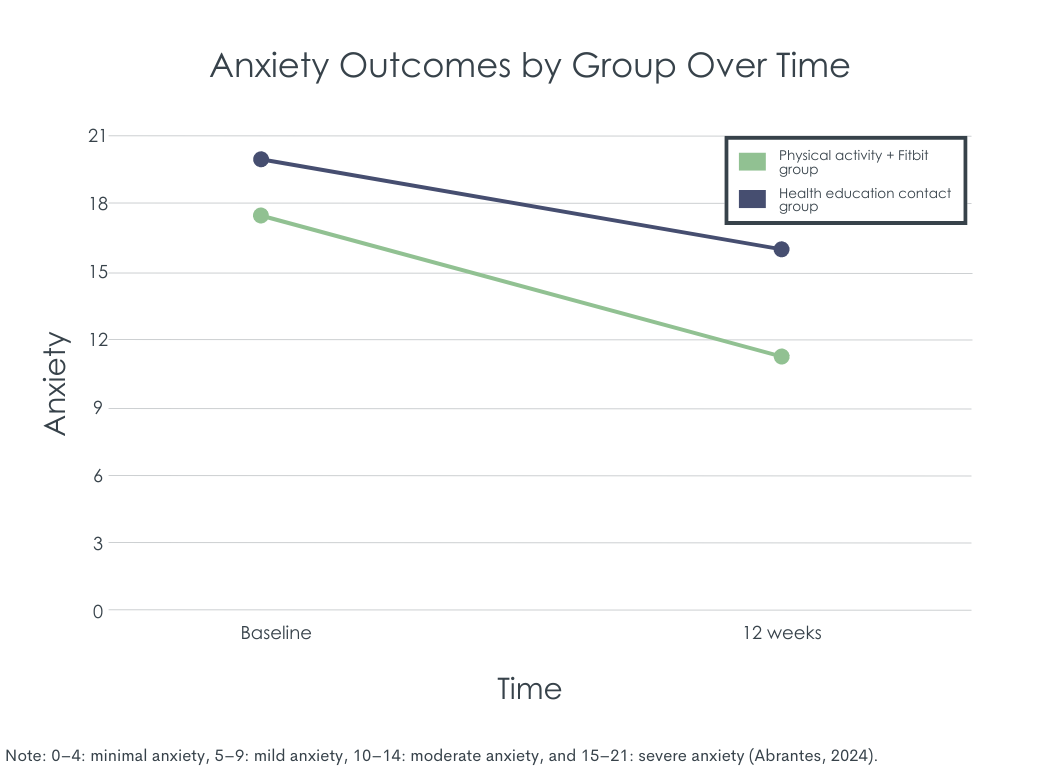

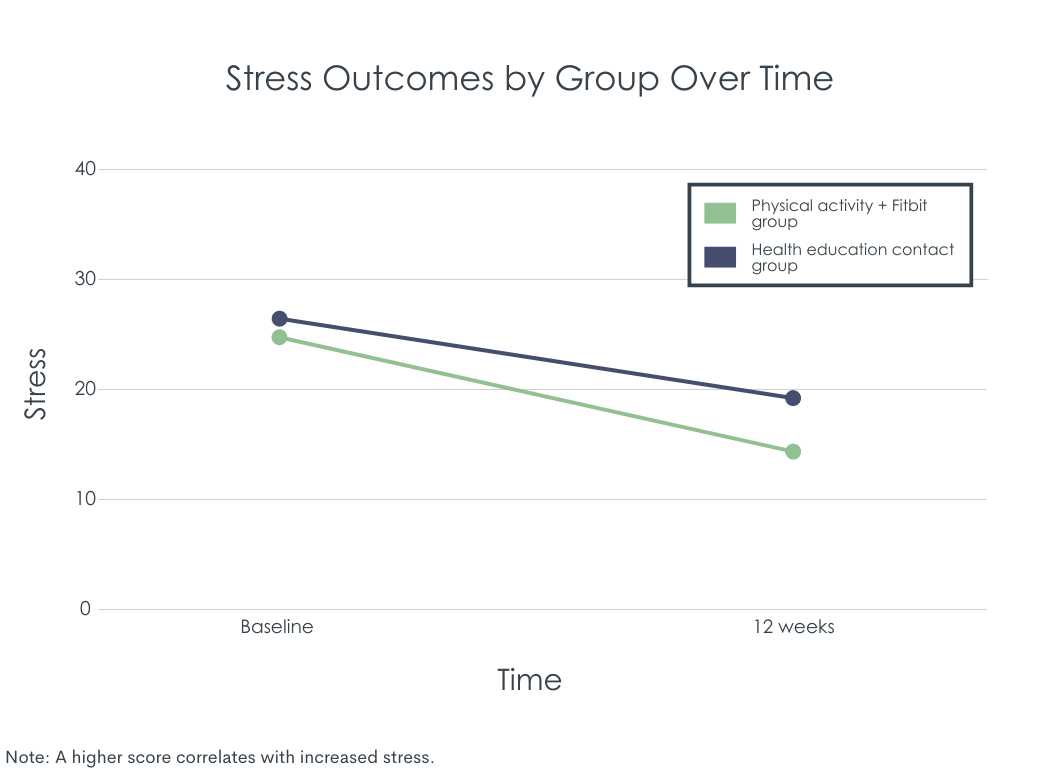

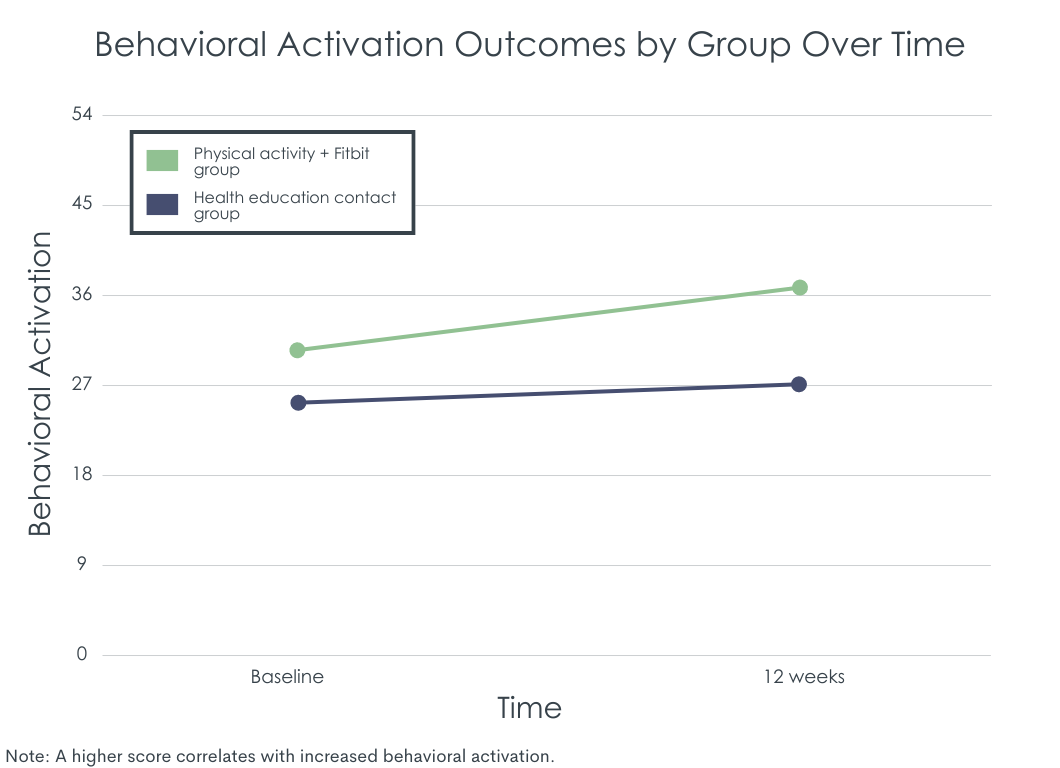

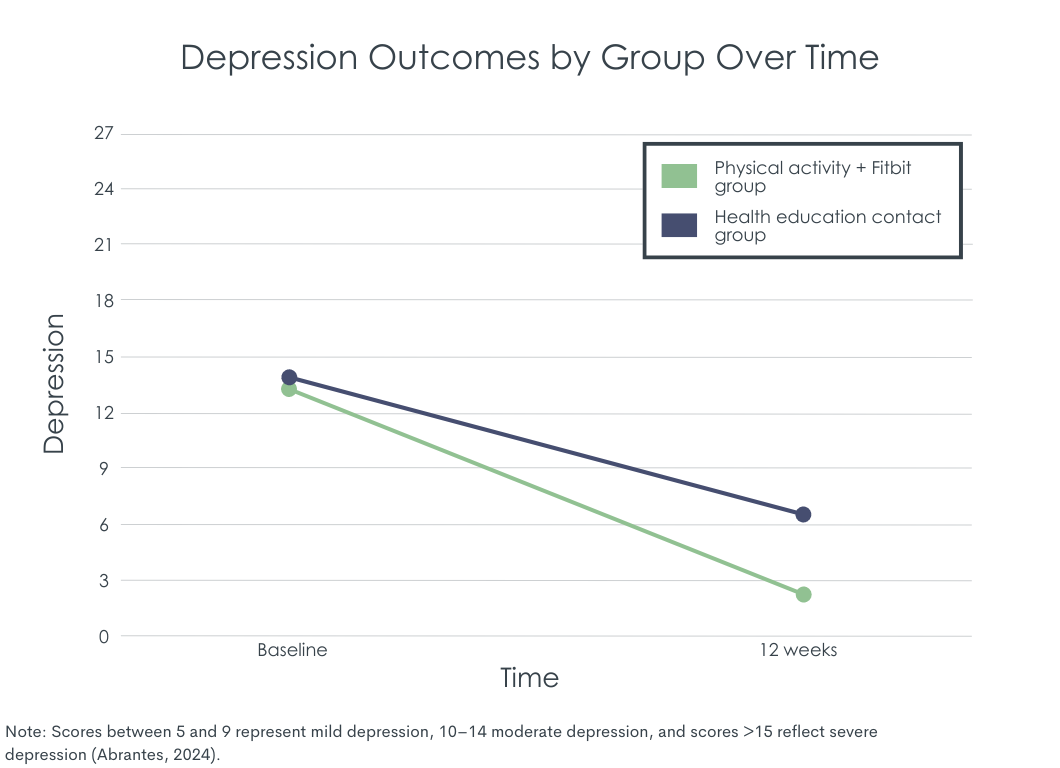

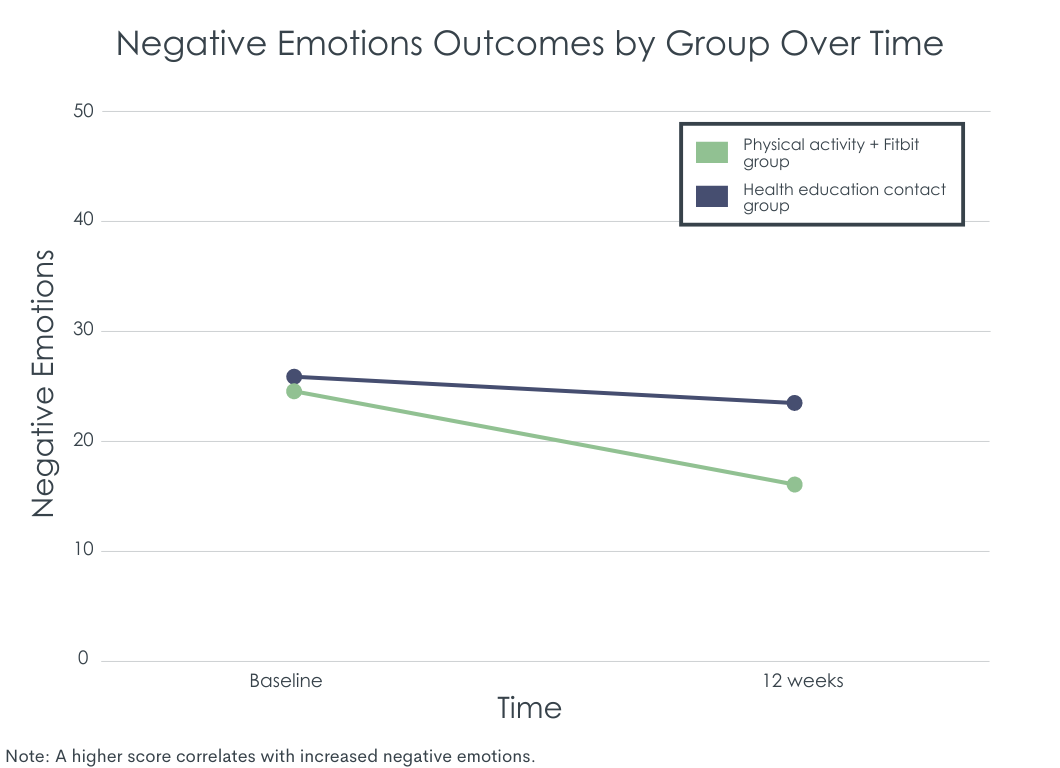

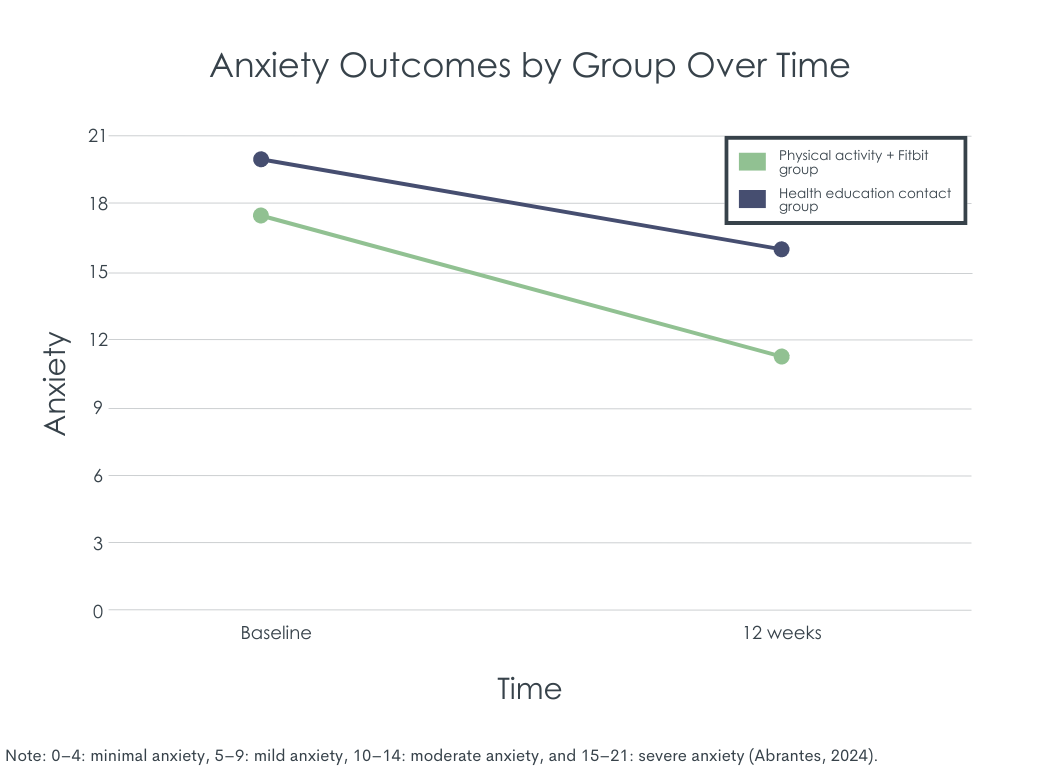

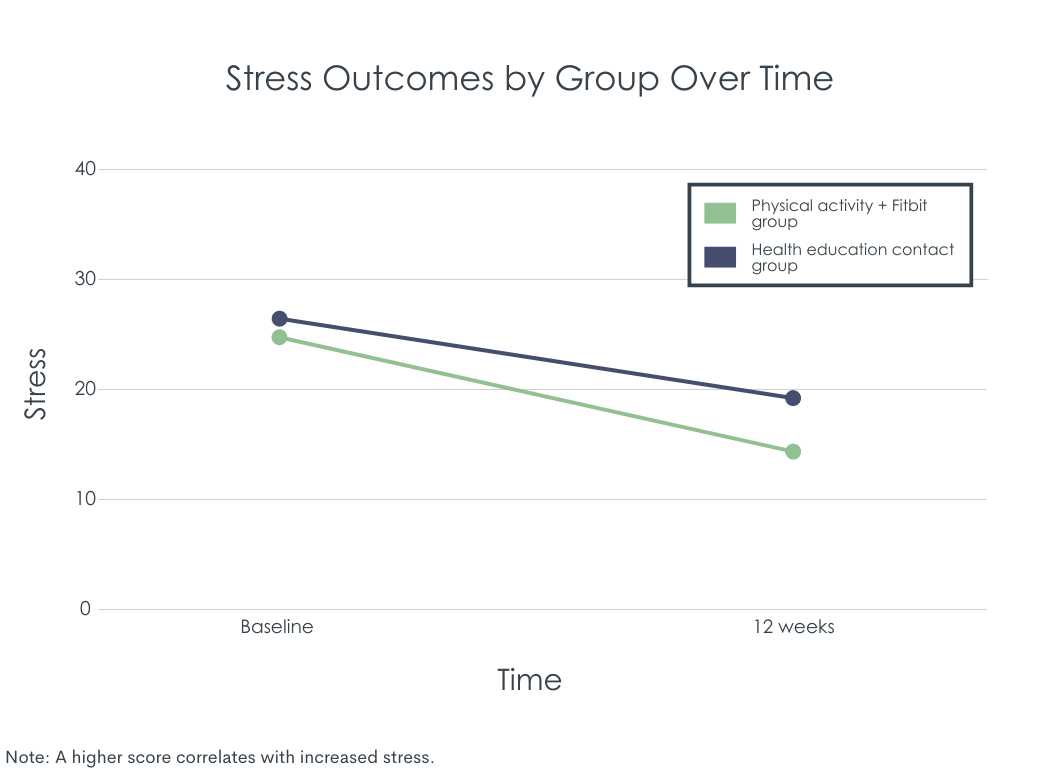

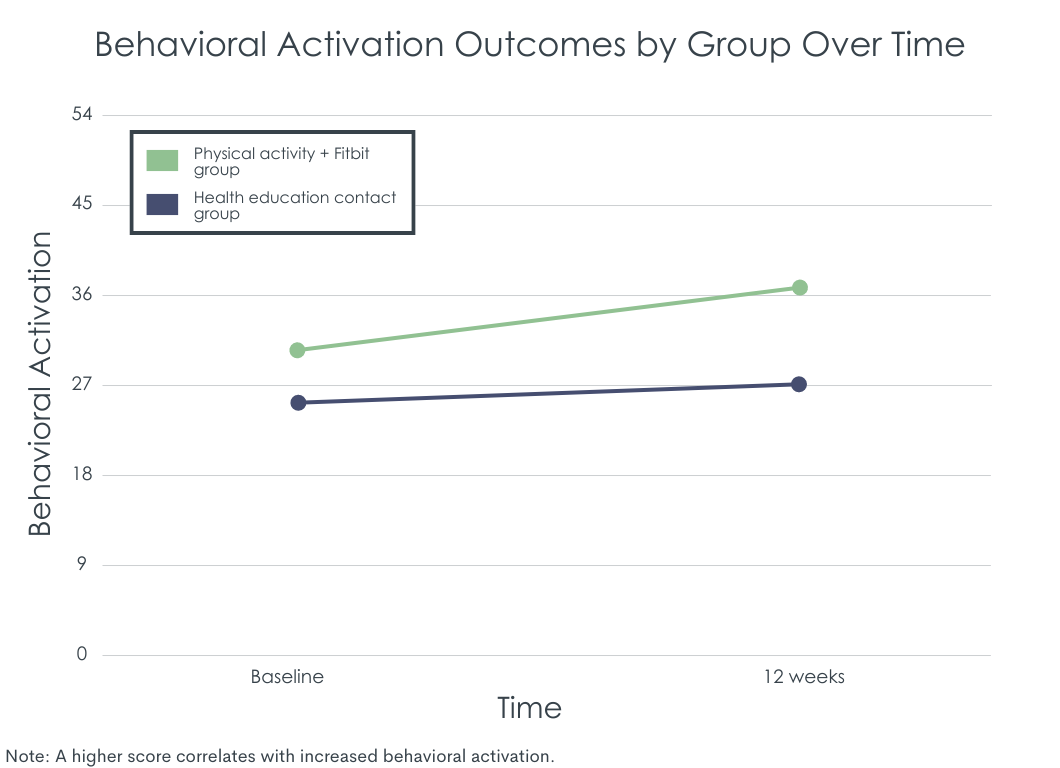

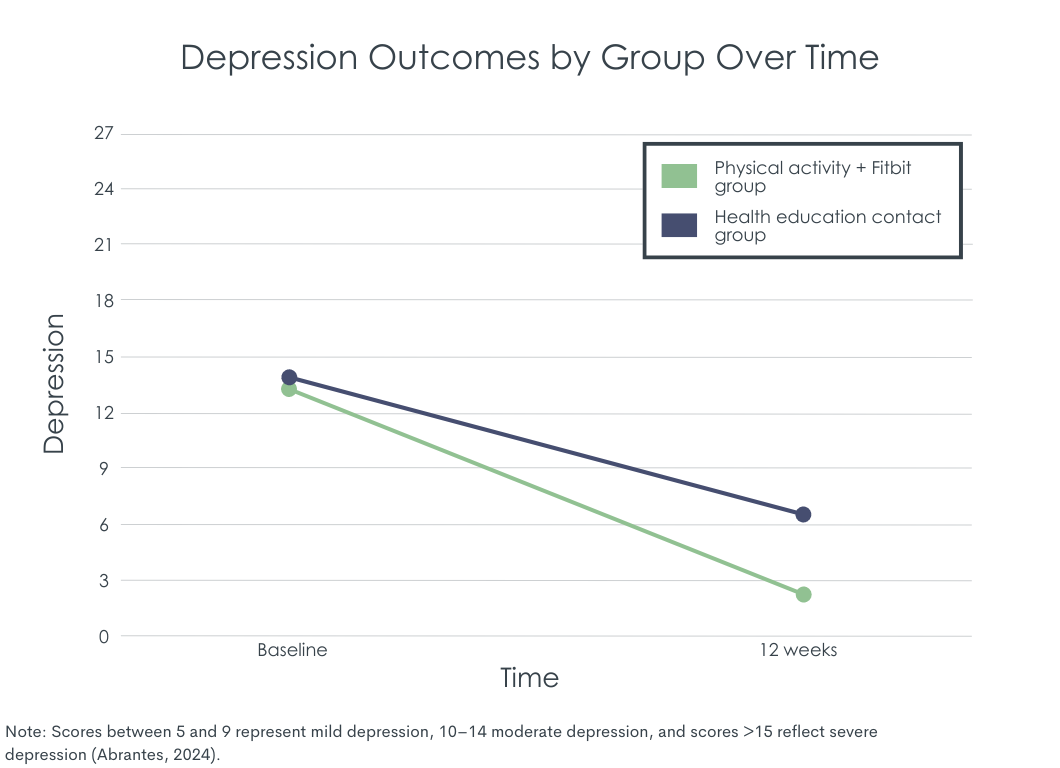

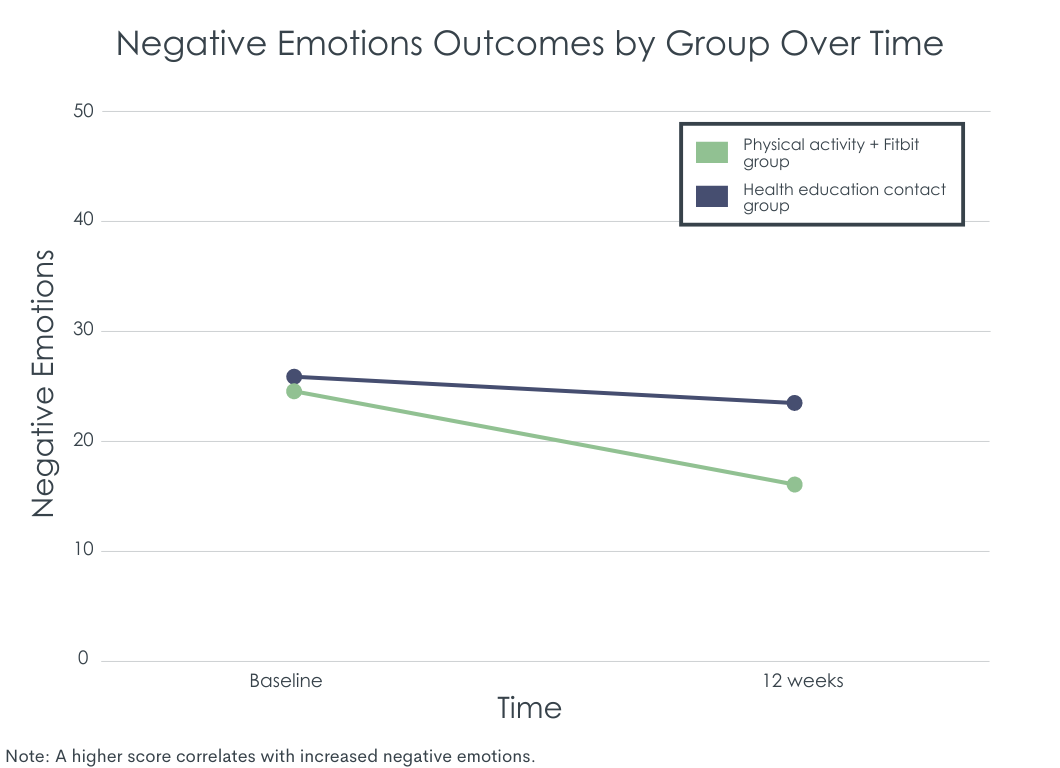

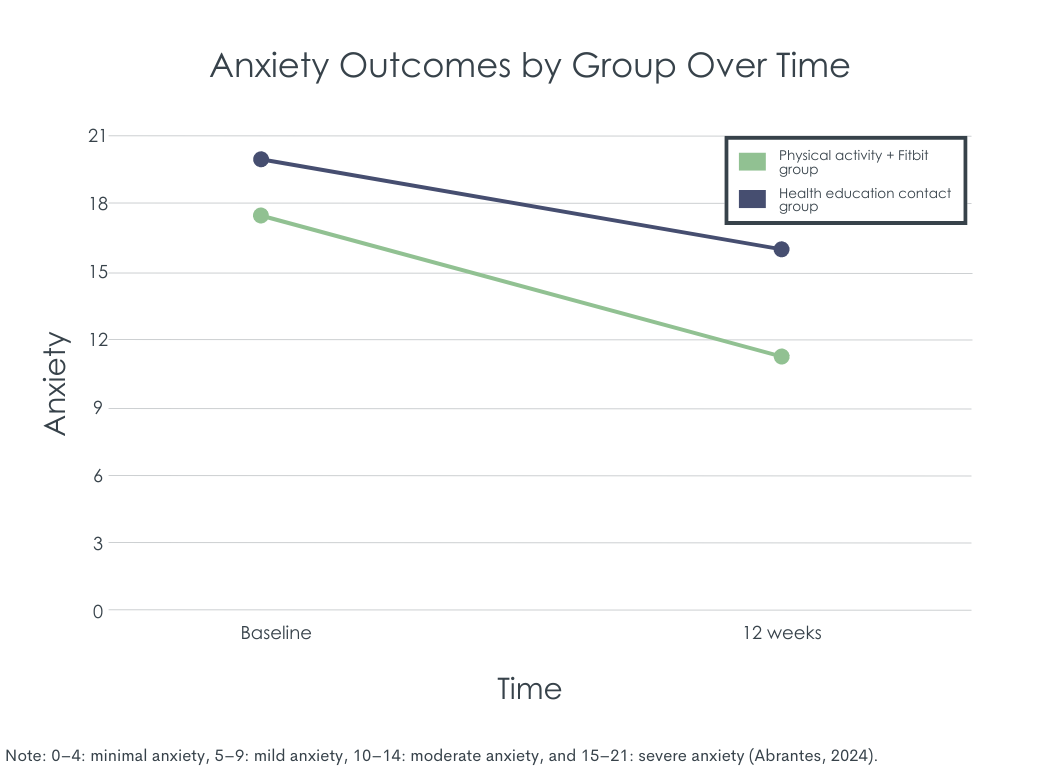

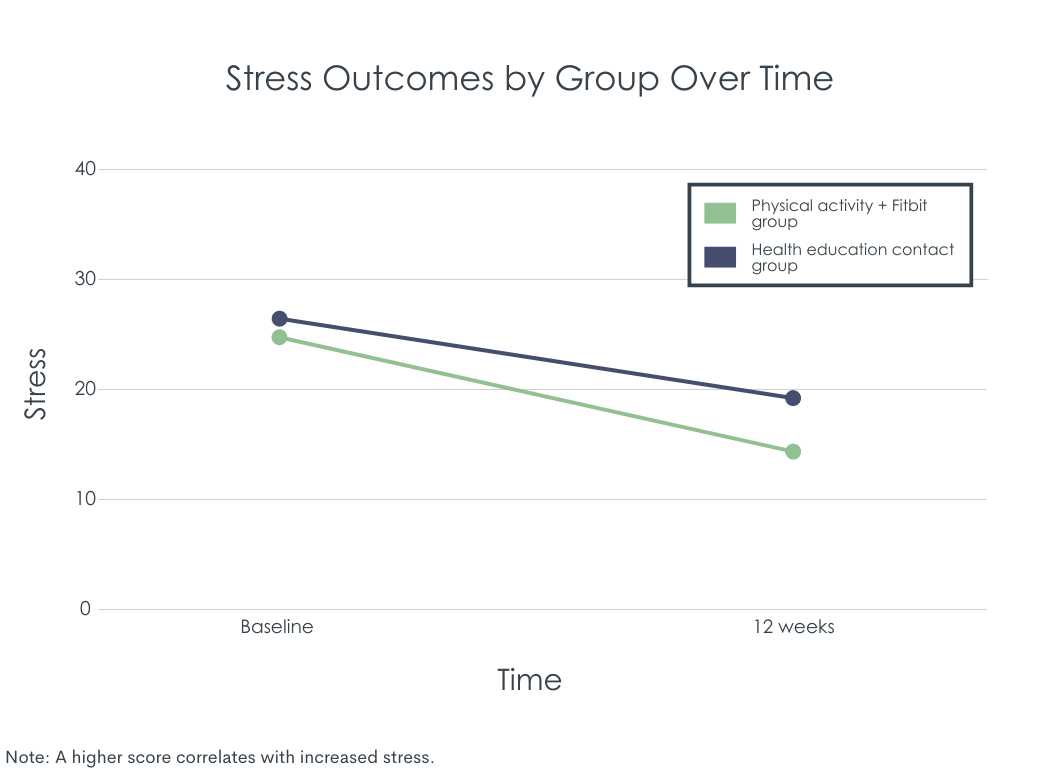

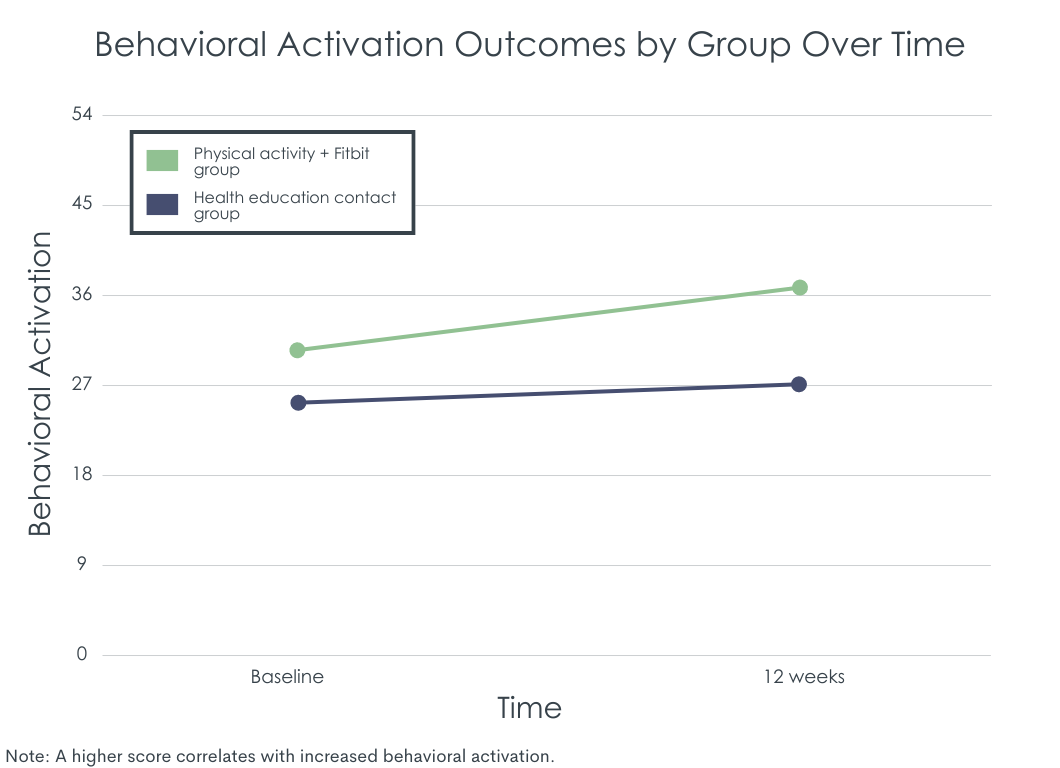

At the end of study assessment, participants in the physical activity group endorsed less depression, overall negative emotions, anxiety, and stress, and greater behavioral activation and physical activity. Notably, all these between group differences were large enough in magnitude – medium to large – to reach statistical significance despite the study’s small sample size.

Physical activity is part of clinical and public health recommendations for a range of mental health problems including depression and anxiety. More recently, a small but growing body of research has begun investigating the potential of physical activity to support substance use disorder recovery. In this study, the researchers tested a novel, telephone-delivered intervention designed to increase physical activity in individuals engaged in outpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder.

The study summarized here was a pilot study with a small sample, which is common in these early investigations. Small sample sizes can make it hard to obtain a statistically significant advantage even when an intervention appears to be helpful. In this study, for example, the intervention substantially increased physical exercise compared to an education-only comparison group (increases of 150 vs. 30 minutes of exercise per week). That said, the novel intervention did not improve percent days abstinent or reduce heavy drinking more than a health education control condition.

Findings were most notable for the indicated benefits of physical activity on depression, negative emotionality, anxiety, and stress. Though the effects of drinking outcomes were roughly equal, physical activity could be offering something of real value, as these emotion and mood states are all risk factors for alcohol use disorder relapse, especially once individuals are no longer receiving the active support provided by treatment. These findings are also consistent with previous research that has, on average, shown a benefit of physical activity on mood in people with substance use disorder. It is possible that these benefits of exercise on potential relapse risk factors may show alcohol use differences over longer periods of time, e.g., follow-ups over the course of 1 or more years. Indeed, negative findings like this have been reported in some previous studies of physical activity for substance use disorder, though a recent meta-analysis suggests an overall benefit.

Physical activity was associated with medium to large effect size benefits in change in depression, negative emotionality, anxiety, and stress in this sample of women in treatment for alcohol use disorder. The physical activity intervention, however, did not improve alcohol use outcomes during the 12-week study, relative to a health education comparison. The benefits on mood and anxiety found in favor of the novel activity intervention may ultimately reduce alcohol use over a longer period of time by reducing overall relapse risk. Future research should test this as well the potential for other kinds of health benefits. Other research shows that for some individuals, physical activity can also help reduce substance use.

Abrantes, A. M., Browne, J., Stein, M. D., Anderson, B., Iacoi, S., Barter, S., Shah, Z., Read, J., & Battle, C. (2024). A lifestyle physical activity intervention for women in alcohol treatment: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Subst Use Addict Treat, 163, 209406. doi.: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209406

l

The benefits of physical activity on mood and well-being are well known. Some studies have also suggested that physical activity may support alcohol use disorder recovery, with a recent review suggesting benefits related to improved cognitive functioning, reduced impulsivity, improved emotion regulation, and reduced craving. Physical activity-based interventions may be especially helpful for people seeking recovery from alcohol use disorder who are experiencing common negative emotions like anxiety and depression, and the distressing discomfort of craving, or who have a goal of improving physical fitness.

The researchers behind this study thought that women may be especially inclined to engage in physical activity-based interventions for alcohol use disorder, because on average, women with alcohol use disorder tend to struggle more with anxiety and depression and are more motivated for physical fitness than men.

This study tested a novel, 12-week, telephone-delivered intervention for increasing physical activity in women participating in a partial hospital program for alcohol use disorder, comparing it to an active control group receiving telephone-delivered health education.

This was a pilot, randomized controlled, trial with 50 women in a partial hospital program (short-term, intensive outpatient treatment) for alcohol use disorder who received either a 12-week, telephone-delivered intervention for increasing physical activity, or 12 weeks of telephone-delivered health education, to determine whether physical activity is superior for reducing alcohol use lapses, alcohol craving, anxiety, depression, and stress, while increasing behavioral activation and exercise. Participants were on average 50 years of age, with 92% of the sample identifying as White, and 6% as Latina.

The study’s physical activity intervention included an initial hour-long orientation in which a study clinician provided information regarding the acute and long-term psychological and physiological benefits of increasing physical activity. Participants also received instructions about how physical activity can be utilized as a coping strategy for managing challenging emotions or alcohol cravings, as well as information on the public health guidelines for physical activity and how to determine if their physical activity is moderate intensity. The study clinician also provided instruction in the use of a Fitbit activity tracker, which participants wore for the 12-week duration of the study intervention, and helped participants brainstorm strategies for integrating physical activity into their schedules. Participants were given a starting step-count goal of 4500 steps per day with a plan for increasing 500 steps per day each week of the intervention.

Study clinicians then called participants at study weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 for a 30-minute phone session to review progress and troubleshoot barriers to achieving physical activity goals. Study clinicians also engaged participants in a brief discussion about physical activity to cope with negative emotions and cravings (weeks 1 & 2), getting and staying motivated + social support (week 4), identifying and overcoming barriers and getting back on track (weeks 6 & 8); and making plans for action and maintenance of physical activity (week 10). Participants also received brief text messages twice per week that reminded them of their current step count goal, and offered feedback and encouragement for achieving increases in their physical activity.

The participants randomized to the active control condition received the same contact time with research staff, however, the content of the material covered, and instructions differed. The active control group received 30-minute telephone sessions following the same schedule as the physical activity intervention group, however, no information about the potential benefits of physical activity were provided, nor were participants instructed to change their current levels of physical activity. Instead, participants received education in a variety of health and lifestyle topics like nutrition, sleep hygiene, and relaxation training. Participants also received text messages twice a week that provided supporting information about the topics covered in the education sessions.

Study inclusion criteria included: 1) being female, 2) ages 18–65, 3) having alcohol use disorder, 4) being currently enrolled in alcohol use disorder treatment, 5) having at least mild depressive symptoms, and 6) having low physical activity (defined as less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week for the past six months). Individuals were excluded if they had medical or psychological conditions that would make it unsafe for them to participate.

Outcomes included alcohol use (including percent days abstinent, percent of heavy drinking days, percent days of no heavy drinking, and mean drinks per day over the 12-week study period), alcohol craving, depression, positive and negative emotionality, behavioral activation (measuring avoidance/rumination, work/school impairment, and social impairment), stress, and physical activity.

Engagement with the Fitbit device was good, but study attrition was notable

In the physical activity group, participants wore the Fitbit on 71% of days, while 80% of the sample wore the Fitbit for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the intervention, with 56% utilizing the Fitbit mobile app each day. In both groups, participants had, on average, 5 out of 6 possible phone call sessions. Among participants who wore the Fitbit for at least 6 weeks, there were significant increases in the number of steps/day (from 4,338 at baseline to 8,600 at 12-week intervention). The intervention group increased their overall physical activity more than the education comparison group (see figure below), a medium-sized effect that did not reach statistical significance in this small sample pilot study.

Drinking outcomes were similar but physical activity was associated with less alcohol craving

Drinking outcomes were similar but physical activity was associated with less alcohol craving

For participants who completed the end of study assessment, 56% of those in the physical activity group maintained alcohol abstinence throughout the 12-week study period, versus 33% for the control group, a difference that did not reach statistical significance likely also in part because of the study’s small sample. They also had less past-week craving with the magnitude of this effect medium in size, also a nonsignificant difference, however. On the other hand, measures of alcohol use such as percent days abstinent and percent days with no heavy drinking (see figures below), were similar between the two groups.

Physical activity was associated with better mental health outcomes

At the end of study assessment, participants in the physical activity group endorsed less depression, overall negative emotions, anxiety, and stress, and greater behavioral activation and physical activity. Notably, all these between group differences were large enough in magnitude – medium to large – to reach statistical significance despite the study’s small sample size.

Physical activity is part of clinical and public health recommendations for a range of mental health problems including depression and anxiety. More recently, a small but growing body of research has begun investigating the potential of physical activity to support substance use disorder recovery. In this study, the researchers tested a novel, telephone-delivered intervention designed to increase physical activity in individuals engaged in outpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder.

The study summarized here was a pilot study with a small sample, which is common in these early investigations. Small sample sizes can make it hard to obtain a statistically significant advantage even when an intervention appears to be helpful. In this study, for example, the intervention substantially increased physical exercise compared to an education-only comparison group (increases of 150 vs. 30 minutes of exercise per week). That said, the novel intervention did not improve percent days abstinent or reduce heavy drinking more than a health education control condition.

Findings were most notable for the indicated benefits of physical activity on depression, negative emotionality, anxiety, and stress. Though the effects of drinking outcomes were roughly equal, physical activity could be offering something of real value, as these emotion and mood states are all risk factors for alcohol use disorder relapse, especially once individuals are no longer receiving the active support provided by treatment. These findings are also consistent with previous research that has, on average, shown a benefit of physical activity on mood in people with substance use disorder. It is possible that these benefits of exercise on potential relapse risk factors may show alcohol use differences over longer periods of time, e.g., follow-ups over the course of 1 or more years. Indeed, negative findings like this have been reported in some previous studies of physical activity for substance use disorder, though a recent meta-analysis suggests an overall benefit.

Physical activity was associated with medium to large effect size benefits in change in depression, negative emotionality, anxiety, and stress in this sample of women in treatment for alcohol use disorder. The physical activity intervention, however, did not improve alcohol use outcomes during the 12-week study, relative to a health education comparison. The benefits on mood and anxiety found in favor of the novel activity intervention may ultimately reduce alcohol use over a longer period of time by reducing overall relapse risk. Future research should test this as well the potential for other kinds of health benefits. Other research shows that for some individuals, physical activity can also help reduce substance use.

Abrantes, A. M., Browne, J., Stein, M. D., Anderson, B., Iacoi, S., Barter, S., Shah, Z., Read, J., & Battle, C. (2024). A lifestyle physical activity intervention for women in alcohol treatment: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Subst Use Addict Treat, 163, 209406. doi.: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209406

l

The benefits of physical activity on mood and well-being are well known. Some studies have also suggested that physical activity may support alcohol use disorder recovery, with a recent review suggesting benefits related to improved cognitive functioning, reduced impulsivity, improved emotion regulation, and reduced craving. Physical activity-based interventions may be especially helpful for people seeking recovery from alcohol use disorder who are experiencing common negative emotions like anxiety and depression, and the distressing discomfort of craving, or who have a goal of improving physical fitness.

The researchers behind this study thought that women may be especially inclined to engage in physical activity-based interventions for alcohol use disorder, because on average, women with alcohol use disorder tend to struggle more with anxiety and depression and are more motivated for physical fitness than men.

This study tested a novel, 12-week, telephone-delivered intervention for increasing physical activity in women participating in a partial hospital program for alcohol use disorder, comparing it to an active control group receiving telephone-delivered health education.

This was a pilot, randomized controlled, trial with 50 women in a partial hospital program (short-term, intensive outpatient treatment) for alcohol use disorder who received either a 12-week, telephone-delivered intervention for increasing physical activity, or 12 weeks of telephone-delivered health education, to determine whether physical activity is superior for reducing alcohol use lapses, alcohol craving, anxiety, depression, and stress, while increasing behavioral activation and exercise. Participants were on average 50 years of age, with 92% of the sample identifying as White, and 6% as Latina.

The study’s physical activity intervention included an initial hour-long orientation in which a study clinician provided information regarding the acute and long-term psychological and physiological benefits of increasing physical activity. Participants also received instructions about how physical activity can be utilized as a coping strategy for managing challenging emotions or alcohol cravings, as well as information on the public health guidelines for physical activity and how to determine if their physical activity is moderate intensity. The study clinician also provided instruction in the use of a Fitbit activity tracker, which participants wore for the 12-week duration of the study intervention, and helped participants brainstorm strategies for integrating physical activity into their schedules. Participants were given a starting step-count goal of 4500 steps per day with a plan for increasing 500 steps per day each week of the intervention.

Study clinicians then called participants at study weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 for a 30-minute phone session to review progress and troubleshoot barriers to achieving physical activity goals. Study clinicians also engaged participants in a brief discussion about physical activity to cope with negative emotions and cravings (weeks 1 & 2), getting and staying motivated + social support (week 4), identifying and overcoming barriers and getting back on track (weeks 6 & 8); and making plans for action and maintenance of physical activity (week 10). Participants also received brief text messages twice per week that reminded them of their current step count goal, and offered feedback and encouragement for achieving increases in their physical activity.

The participants randomized to the active control condition received the same contact time with research staff, however, the content of the material covered, and instructions differed. The active control group received 30-minute telephone sessions following the same schedule as the physical activity intervention group, however, no information about the potential benefits of physical activity were provided, nor were participants instructed to change their current levels of physical activity. Instead, participants received education in a variety of health and lifestyle topics like nutrition, sleep hygiene, and relaxation training. Participants also received text messages twice a week that provided supporting information about the topics covered in the education sessions.

Study inclusion criteria included: 1) being female, 2) ages 18–65, 3) having alcohol use disorder, 4) being currently enrolled in alcohol use disorder treatment, 5) having at least mild depressive symptoms, and 6) having low physical activity (defined as less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week for the past six months). Individuals were excluded if they had medical or psychological conditions that would make it unsafe for them to participate.

Outcomes included alcohol use (including percent days abstinent, percent of heavy drinking days, percent days of no heavy drinking, and mean drinks per day over the 12-week study period), alcohol craving, depression, positive and negative emotionality, behavioral activation (measuring avoidance/rumination, work/school impairment, and social impairment), stress, and physical activity.

Engagement with the Fitbit device was good, but study attrition was notable

In the physical activity group, participants wore the Fitbit on 71% of days, while 80% of the sample wore the Fitbit for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the intervention, with 56% utilizing the Fitbit mobile app each day. In both groups, participants had, on average, 5 out of 6 possible phone call sessions. Among participants who wore the Fitbit for at least 6 weeks, there were significant increases in the number of steps/day (from 4,338 at baseline to 8,600 at 12-week intervention). The intervention group increased their overall physical activity more than the education comparison group (see figure below), a medium-sized effect that did not reach statistical significance in this small sample pilot study.

Drinking outcomes were similar but physical activity was associated with less alcohol craving

Drinking outcomes were similar but physical activity was associated with less alcohol craving

For participants who completed the end of study assessment, 56% of those in the physical activity group maintained alcohol abstinence throughout the 12-week study period, versus 33% for the control group, a difference that did not reach statistical significance likely also in part because of the study’s small sample. They also had less past-week craving with the magnitude of this effect medium in size, also a nonsignificant difference, however. On the other hand, measures of alcohol use such as percent days abstinent and percent days with no heavy drinking (see figures below), were similar between the two groups.

Physical activity was associated with better mental health outcomes

At the end of study assessment, participants in the physical activity group endorsed less depression, overall negative emotions, anxiety, and stress, and greater behavioral activation and physical activity. Notably, all these between group differences were large enough in magnitude – medium to large – to reach statistical significance despite the study’s small sample size.

Physical activity is part of clinical and public health recommendations for a range of mental health problems including depression and anxiety. More recently, a small but growing body of research has begun investigating the potential of physical activity to support substance use disorder recovery. In this study, the researchers tested a novel, telephone-delivered intervention designed to increase physical activity in individuals engaged in outpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder.

The study summarized here was a pilot study with a small sample, which is common in these early investigations. Small sample sizes can make it hard to obtain a statistically significant advantage even when an intervention appears to be helpful. In this study, for example, the intervention substantially increased physical exercise compared to an education-only comparison group (increases of 150 vs. 30 minutes of exercise per week). That said, the novel intervention did not improve percent days abstinent or reduce heavy drinking more than a health education control condition.

Findings were most notable for the indicated benefits of physical activity on depression, negative emotionality, anxiety, and stress. Though the effects of drinking outcomes were roughly equal, physical activity could be offering something of real value, as these emotion and mood states are all risk factors for alcohol use disorder relapse, especially once individuals are no longer receiving the active support provided by treatment. These findings are also consistent with previous research that has, on average, shown a benefit of physical activity on mood in people with substance use disorder. It is possible that these benefits of exercise on potential relapse risk factors may show alcohol use differences over longer periods of time, e.g., follow-ups over the course of 1 or more years. Indeed, negative findings like this have been reported in some previous studies of physical activity for substance use disorder, though a recent meta-analysis suggests an overall benefit.

Physical activity was associated with medium to large effect size benefits in change in depression, negative emotionality, anxiety, and stress in this sample of women in treatment for alcohol use disorder. The physical activity intervention, however, did not improve alcohol use outcomes during the 12-week study, relative to a health education comparison. The benefits on mood and anxiety found in favor of the novel activity intervention may ultimately reduce alcohol use over a longer period of time by reducing overall relapse risk. Future research should test this as well the potential for other kinds of health benefits. Other research shows that for some individuals, physical activity can also help reduce substance use.

Abrantes, A. M., Browne, J., Stein, M. D., Anderson, B., Iacoi, S., Barter, S., Shah, Z., Read, J., & Battle, C. (2024). A lifestyle physical activity intervention for women in alcohol treatment: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Subst Use Addict Treat, 163, 209406. doi.: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209406