Non-abstinent recovery approaches are common, though abstinence associated with better quality of life

Abstinence-based models of recovery tend to dominate the treatment landscape, yet many people continue some level of use. This study reported the prevalence of people in recovery who are currently abstinent or engaging in some substance use, and examined the link between substance use status and functioning and well-being.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Historically, the addiction treatment infrastructure in the United States leveraged 12-step models of recovery, which emphasize and recommend abstinence. While the treatment landscape has changed considerably during the latter part of the 20th and beginning of the 21st century, abstinence-based models of addiction recovery continue to dominate the substance use disorder treatment landscape. Accordingly, some individuals with substance use problems may be hesitant to engage in care because of perceptions that an abstinence goal is required to enter treatment. However, abstinence may not always be a requirement for resolving a problem with alcohol or other drugs and may not be the only priority for people seeking substance use treatment. In actual fact, abstinence is not a requirement for substance use disorder remission according to the current official diagnosis classification systems, which assesses symptoms caused by alcohol/drug use rather than assessing the frequency and quantity of alcohol/drug use itself. For example, approximately 1/4 of individuals in alcohol use disorder remission engage in regular or occasional heavy alcohol use and about 1/3 engage in regular or occasional low risk alcohol use without problems – meaning they once met criteria for alcohol use disorder and are subsequently symptom free for 1 year and currently drink (heavy alcohol use is defined by NIAAA: for men, >4 drinks on any day or >14 drinks per week; for women, >3 drinks on any day or >7 drinks per week).

At the same time, prior research suggests there are benefits to abstinence, including better recovery outcomes and more stable recovery. But, much of this past work has focused on individuals with alcohol use disorder, and has not included individuals who have other drug use disorders nor considered substance use that might be considered ‘secondary’ to the ‘primary problem’ substance. By expanding this body of research, more might be learned about what kinds of substance use goals will maximize well-being, reduce health risks, and engage as many people as possible who can benefit from care.

This study estimated the prevalence of adults in recovery in the U.S. who are abstinent or currently using substances moderately. It also tested whether different substance use statuses in recovery were related to different demographic or clinical characteristics and measures of current well-being.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary analysis using data from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults that “once had a problem with alcohol or drugs but no longer do” (i.e., substance use problem resolution; the National Recovery Study). The current analysis examined the relationships between participants’ substance use status, demographic, clinical, and recovery-related characteristics, and indicators of current well-being.

The 2,002 participants in this study were recruited using an online survey response pool company that maintains a nationally representative sample of US adults for research purposes. A nationally representative group of 39,809 individuals were sent a screening question via email, to which 25,229 responded (63.4%).

Participants were also asked to identify from a list of substances which drugs they had used 10 times or more in their life. This list included alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, narcotics other than heroin, methadone, buprenorphine, amphetamines, methamphetamine, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, hallucinogens, synthetic marijuana/synthetic drugs, inhalants, steroids, or other. Then participants were asked how old they were when they first used each substance, when they started regular use (i.e., weekly), if applicable, and how old they were when they last used that substance. Participants were also asked which of the substances were a problem for them and which they would consider their primary substance or ‘drug of choice.’

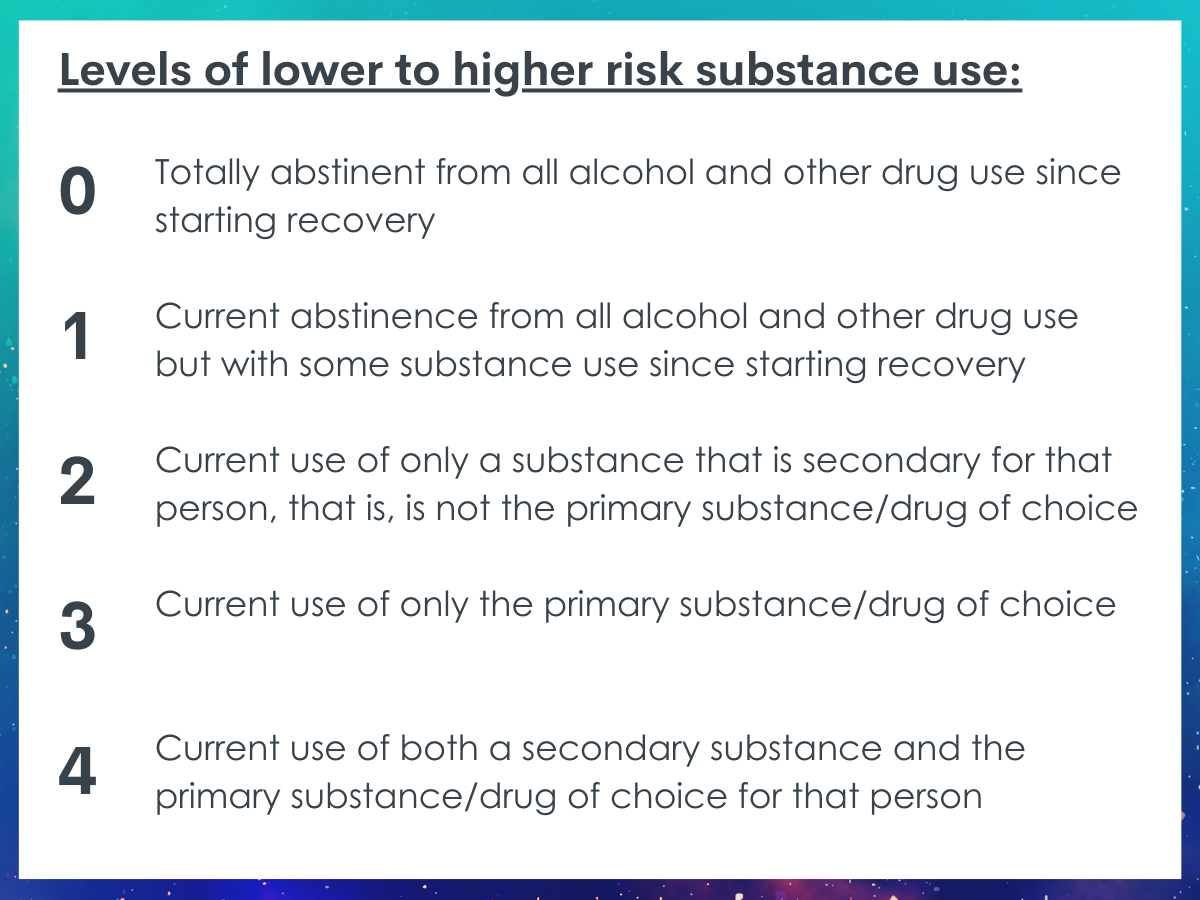

Participants were then grouped into different substance use statuses based on their current abstinence or substance use at the time of the survey. Each status was ordered from lower to higher risk substance use (0 = lowest risk to 4 = highest risk): 0) totally abstinent from all alcohol and other drug use since starting recovery; 1) current abstinence from all alcohol and other drug use but with some substance use since starting recovery; 2) current use of only a substance that is secondary for that person, that is, is not the primary substance/drug of choice; 3) current use of only the primary substance/drug of choice; 4) current use of both a secondary substance and the primary substance/drug of choice for that person.

Participants were also asked how long (years and months) it had been since they had resolved their problem with alcohol/drugs, how many “serious” attempts they had made to resolve their alcohol/drug problem before they overcame it, if they had ever received outpatient or inpatient alcohol/drug treatment in their lifetime, and if they had ever attended 12-step meetings regularly (at least once per week). Participants were also presented a list of substance use and mental health conditions and asked to indicate which they had ever been diagnosed with. Number of psychiatric diagnoses included alcohol and other substance use disorders.

Participants were also asked about their current levels of self-esteem, happiness, quality of life, recovery capital, and psychological distress using a number of brief validated measures.

Before performing any analyses, participants were weighted to make the sample representative of the U.S. population. That way, if the sample had more representation from one group than another, the weighting process gives more weight to participants who are underrepresented and less weight to participants who are overrepresented, effectively evening out the sample characteristics to more accurately represent the prevalence in the U.S. population. Then the research team tested the association between demographic and clinical characteristics and current substance use status to assess if certain factors, such as time in recovery, would be associated with a higher or lower risk status. Lastly, they tested the association between substance use status and measures of well-being while controlling for clinical characteristics (demographic variables, primary substance, age of initiation of regular substance use, years since substance use problem resolution, number of “serious” attempts, number of psychiatric diagnoses, formal treatment history, and regular 12-step attendance). Statistically controlling for these clinical characteristics helps to isolate the association between substance use status and the indices of current well-being to better assess the independent effect of substance use status in relation to well-being.

A large proportion of the participants were either younger adults (45% were 25 to 49 years old) or middle aged (35% were 50 to 64 years old). A little less than half of participants were female (40%) and 60% were male. In terms of race and ethnicity, 62% of participants were White/non-Hispanic, 14% were Black/non-Hispanic, and 17% were Hispanic. The average time in recovery was 12 years, with a broad range of anywhere from a few weeks to 40 or more years.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Substance use is commonly endorsed among those who report having resolved an alcohol or other drug problem.

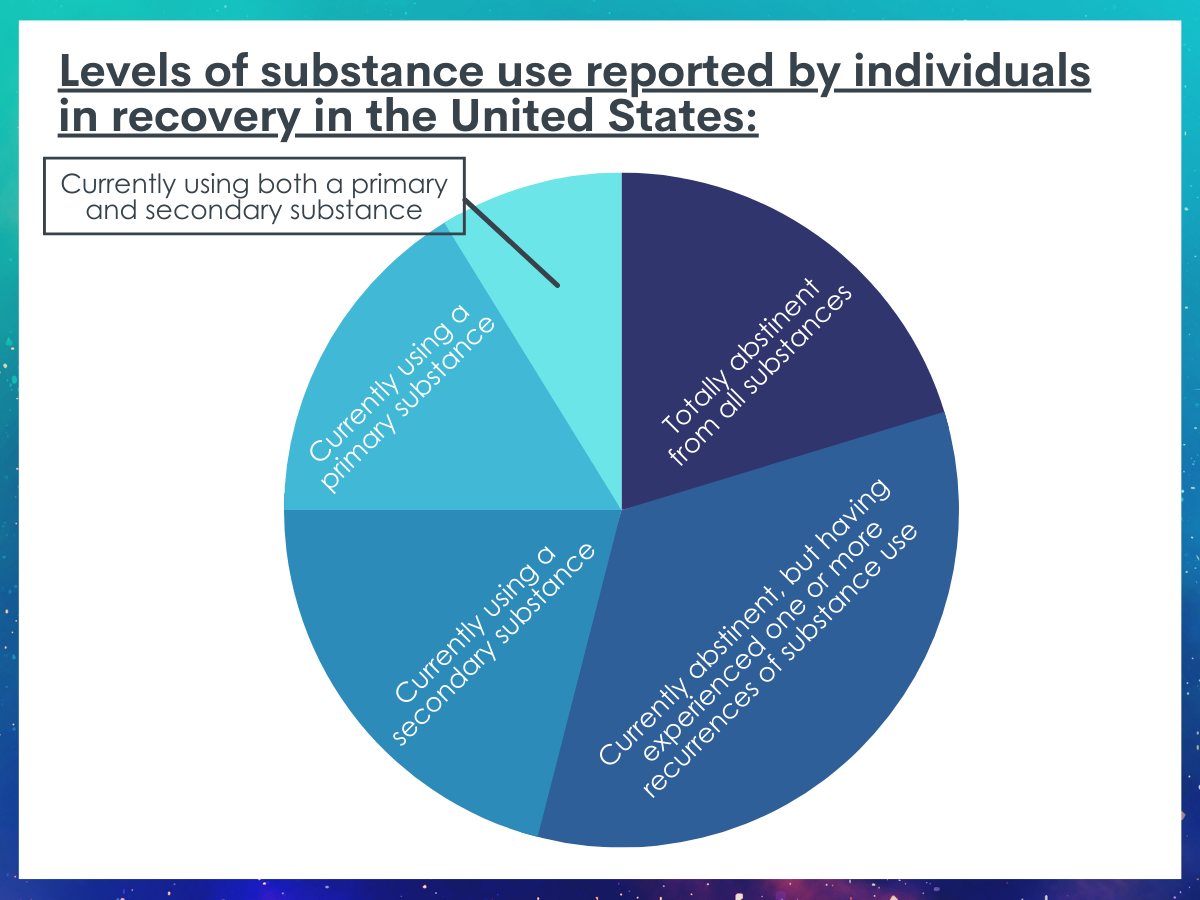

Results from this study estimated that in 2016, 20.3% of individuals in recovery in the U.S. had been totally abstinent from all alcohol and other drug use since being their recovery. 33.7% were currently abstinent, but reported at least one or more prior occurrences of alcohol or other drug use since their recovery, 21% were currently using a secondary substance, 16.2% were currently using their primary substance/drug of choice, and 8.8% were currently using both a secondary substance and their primary substance.

Lower risk substance use status associated with greater well-being.

Lower risk substance use status was associated independently with greater recovery capital, less psychological distress, greater self-esteem, greater happiness, and greater quality of life and functioning; whereas higher risk substance use status was associated independently with less recovery capital, greater psychological distress, less self-esteem, less happiness, and less quality of life and functioning.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Despite abstinence being the dominant model of addiction recovery in the U.S. today, nearly half of adults in recovery in the U.S. reported currently using either a secondary substance, their primary substance, or both. Another 30% were abstinent currently, but reported using substances at some point since resolving their primary substance use problem. This suggests that abstinence is, for many, not a requirement for overcoming an alcohol or other drug use problem. However, lower risk substance use status (e.g., being continuously or currently abstinent) was correlated with greater well-being, including greater recovery capital, self-esteem, happiness, quality of life, and less psychological distress, even after accounting for demographic characteristics, clinical severity factors, and substance use history. These results speak to the value of recommending abstinence while promoting harm reduction approaches when helping individuals who identify a pattern of problematic alcohol or other drug use. Person-centered approaches such as these may best engage individuals in making shifts from higher risk substance use (i.e., using their primary substance and a secondary substance) to lower risk substance use (i.e., using only a secondary substance), while also helping individuals initiate and sustain abstinence if desired through linkages to empirically-supported treatment, recovery support services, and self-management strategies.

Although lower risk abstinent substance use status (either continuous abstinence or current abstinence) was associated with greater well-being, and higher risk substance use status was associated with greater distress, the study cannot speak directly to whether abstinence caused better well-being outcomes, or that current substance use caused worse outcomes. For example, it is possible that participants experiencing greater distress were using more substances to cope, rather than current substance use causing greater distress. That said, other longitudinal studies have found similar benefits associated with abstinence including more stable remission and better functioning and well-being, which support better holistic outcomes attributable to abstinence especially among those with more severe addiction histories.

Additionally, although abstinence has direct salubrious biological and psychological benefits, other factors may also explain why abstinence is associated with greater well-being. Given that abstinence is the dominant model in the U.S., society may place more value on abstinence in recovery. A person who chooses abstinence, for whatever reason, may therefore experience recovery with fewer societal and stigma related barriers creating a more ‘pleasant’ recovery experience. A person in recovery currently using substances may face more stigma and societal barriers, which could be related to worse well-being. On the other hand, abstinence can also lead to feelings of ostracization, shame, and stigma depending on the setting. For example, someone who is a non-drinker being asked, “Why don’t you drink?” in a social setting. However, substance use apart from alcohol is considered criminal behavior at the federal level, and penalties for drug use apart from alcohol and cannabis can be steep. With that in mind, lower risk substance use status (e.g., abstinence) may be related to greater well-being because abstinence provides more access to resources, support, and general encouragement from friends, family, and other important others in an abstinent-dominant environment.

Surprisingly, formal treatment attendance, regular 12-step attendance, or number of serious attempts before resolving a substance use problem were not associated with current substance use status. Formal treatment and especially 12-step organizations are designed for people who want to stop completely, so the researchers would expect to see an association between those and current abstinence. Additionally, a person with a more severe substance use problem may be more likely to try formal treatment or 12-step or may have a greater number of attempts at recovery before achieving problem resolution, theoretically, via abstinence. But there was no relationship between these factors and abstinence in the current sample. Why experiences of formal treatment, 12-step attendance, and number of serious attempts (potential proxies for substance use problem severity and exposure to abstinence-promoting culture) were not associated with abstinence in this study is not readily clear. It is possible that these factors were unrelated to substance use status because the large, nationally representative sample of individuals here represented a broader, more diverse set of recovery experiences relative to a more focused clinical and recovery-identified group.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study is cross-sectional, meaning that researchers don’t know when certain factors happened over time and cannot say that one factor caused another. For example, although lower risk substance use status was associated with greater well-being, the researchers cannot say that lower risk substance use or abstinence caused greater well-being. However, well-being was measured by asking about current experiences or “in the past week” and about 20% of the sample reported being continuously abstinent since being in recovery. For these participants, the researchers can confidently say that abstinence preceded their current reported well-being.

- Due to its cross-sectional nature, it is not known how stable these substance use statuses are for these different groups in this study. It is possible, for example, that some of these recovering individuals who reported using both primary and secondary substances (who also on average were more likely to have lower levels of well-being) may have been at greater risk of relapse and returning to an active problem status.

- Often large, nationally representative surveys have to limit the number of questions asked to maximize participant completion rate. This means that some of the questions lack additional details, such as specific timing of events. For example, the question about 12-step attendance reads: “had ever attended 12-step meetings regularly (at least once per week).” This does not capture current attendance or for how long, if the person had worked the steps, etc. This way of measuring some variables misses potential confounds or other correlates. On the same note, as the research team stated, participants categorized in the ‘current substance use’ status group may have been abstinent at some point since resolving their problem, but this is not captured by the study’s measures.

- All measures in the current study were via self-report, meaning, the researchers did not have any objective sources of data (e.g., medical chart review for formal treatment history). Self-report may lead to some recall bias or social desirability bias.

- Although statistically significant, the magnitude of the relationships between different substance use statuses and well-being outcomes were small. This would suggest that benefits of being in a lower versus higher risk use status (e.g., abstinence vs use of a secondary substance) might be less pronounced than say, having a resolved versus unresolved substance use problem. It follows then that facilitating individuals in personalized and achievable substance use goals may be more beneficial than promoting a particular (i.e., abstinence-based) goal. A study comparing participants in recovery versus participants with an unresolved substance use problem may find larger effects on outcomes, such as well-being.

BOTTOM LINE

In the U.S. in 2016, 54% of adults in recovery reported continuous or current abstinence, and 46% reported current use of a secondary substance, primary substance, or both. Lower risk substance use statuses (i.e., continuous abstinence, current abstinence) were associated with more years in recovery, greater recovery capital, self-esteem, happiness, quality of life, and less psychological distress. Higher risk substance use statuses (i.e., current use of secondary substance, primary substance, or both) were associated with younger age of substance use initiation and a greater number of psychiatric diagnoses.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Nearly half of adults in the U.S. in recovery report some current substance use. Based on these findings, it appears that abstinence from alcohol and other drug use is, for many, not a requirement for achieving recovery from a substance use problem. Abstinence was, however, associated with better functioning and well-being and participants tended to gravitate toward abstinence with more time in recovery. With that in mind, abstinence may be recommended, but not required. Tailoring recovery goals to the person’s needs, and that focus on reducing harm, may be an important strategy to best engage individuals with problem alcohol or other drug use to make shifts from higher risk substance use to lower risk substance use, and help individuals start and sustain abstinence if desired through getting connected to evidence-supported treatment, mutual-help organizations and other recovery support services.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Nearly half of adults in the U.S. in recovery report some current substance use. Based on these findings, it appears that abstinence from alcohol and other drug use is, for many, not a requirement for achieving recovery from a substance use problem. Abstinence was associated with better functioning and well-being although these differences were small when accounting for other clinical factors. With that in mind, abstinence may be recommended, but not required. Tailoring recovery goals to be personalized and achievable may be more beneficial than a particular (e.g., abstinence-only) goal by way of engaging the most individuals who report having an alcohol or other drug use problem into care. These person-centered harm reduction approaches can help individuals to make shifts from higher risk substance use to lower risk substance use, and help them start and sustain abstinence if desired through getting connected to evidence-supported treatment, mutual-help organizations and other recovery support services.

- For scientists: Findings from this 2016 nationally representative U.S. cross-sectional sample suggest 54% of adults in recovery reported continuous or current abstinence, and 46% reported current use of a secondary substance, primary substance, or both. Survey weight adjusted regression models suggested lower risk substance use-statuses (i.e., continuous abstinence, current abstinence) were associated with more years in recovery, greater recovery capital, self-esteem, happiness, quality of life, and less psychological distress. Similarly, higher risk substance use-statuses (i.e., current use of secondary substance, primary substance, or both) were associated with younger age of substance use initiation and a greater number of psychiatric diagnoses. Although statistically significant, the variance accounted for in both unadjusted and adjusted models was modest ranging from <1-4%. This suggests that there are many other factors that could influence how someone with a substance use problem is functioning. However, this study is consistent with most naturalistic studies with a heterogeneous sample, where predictors often do not account for very large proportions of variance in mental health and well-being. Future studies should examine these factors longitudinally to support temporal precedence between variables.

- For policy makers: Nearly half of adults in the U.S. in recovery report some current substance use. Based on these findings, it appears that abstinence from alcohol and other drug use is, for many, not a requirement for achieving recovery from a substance use problem. Abstinence was, however, associated with better functioning and well-being. With that in mind, abstinence may be recommended, but not required. Tailoring recovery goals to be personalized, achievable, and focused on reducing harm may be an important strategy to best engage individuals who report an alcohol or other drug use problem to make shifts from higher risk substance use to lower risk substance use, and help them start and sustain abstinence if desired through getting connected to evidence-supported treatment, mutual-help organizations or other recovery support services. Policies that support funding for person-centered harm reduction treatment models and public health campaigns that show multiple pathways to recovery (not simply abstinence-based) may bring more people with substance use problems into care.

CITATIONS

Eddie, D., Bergman, B. G., Hoffman, L. A., & Kelly, J. F. (2021). Abstinence versus moderation recovery pathways following resolution of a substance use problem: Prevalence, predictors, and relationship to psychosocial well‐being in a national United States sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 46(2), 312-325. doi: 10.1111/acer.14765*

*This study features RRI personnel, but was reviewed independently for this Bulletin