What happens to patients’ motivation if they are mandated to treatment? Study finds treatment and motivation for change are high and stable regardless of whether patients were in treatment on a voluntary or involuntary basis

Involuntary commitment of individuals to residential or inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) treatment remains a controversial yet common practice. In this study researchers examined the relationships between treatment motivation, motivation to change, and substance use behavior among patients voluntarily and involuntarily admitted to residential treatment in Norway.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

SUD remains a significant public health concern and debate persists regarding best practices for engaging individuals in treatment, retaining them in care, and facilitating continuing care while improving long-term recovery. Most countries allow for involuntary admission to SUD treatment, usually in cases where the individual becomes self-destructive, demonstrates diminished capacity, or poses a significant threat to themselves or others (e.g., acutely homicidal or suicidal). Advocates maintain that this is an important policy to uphold in order to circumvent motivational barriers, among others, and provide life-saving care. On the other hand, some experts fear that doing so not only hinders autonomy but may also undermine treatment and recovery motivation and long-term outcomes. In order to examine how those involuntarily admitted to SUD treatment may differ from those who voluntary attend, researchers tracked the motivation of patients in Norway during residential treatment, following up with them six months post-treatment to assess outcomes.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was an observational study – measuring 202 patients at admission, discharge, and six-month follow up – to examine differences between patients voluntarily vs. involuntarily admitted to SUD treatment on measures of motivation for change, treatment readiness, and substance use. Patients in this study were recruited from one of three publicly funded medical centers in Kristiansand, Tønsberg, or Oslo Norway. Patients were included in the study if they had a diagnosed substance use disorder, were 18 or older, spoke/understood Norwegian, and were included in the final analysis if they spent at least three weeks in their respective programs. Patients were only excluded if they declined to participate or were determined ineligible due to an intellectual disability.

Patients participated in clinical diagnostic interviews at admission to treatment and also completed self-report motivation measures. The two measures used for this study included the Readiness to Change Questionnaire and the Treatment Readiness Tool to assess motivation/readiness to change substance use at admission (e.g., precontemplation: “I don’t think I drink too much;” contemplation: “I think my drinking is a problem sometimes;” action: “I have just recently changed my drinking habits”) and motivation for treatment at admission and discharge (e.g., “I do not want help from anybody.” vs. “I think I need help.”), respectively. The Readiness to Change Questionnaire is used to categorize individuals into groups based on whether they are in the “precomptemplation” (not ready or not yet considering change), “contemplation” (contemplating and getting ready for change), or “action” (moving forward and taking active steps to change) phases of behavior change. Patients again completed the Treatment Readiness Tool questionnaire at discharge. All patients were then interviewed at six-month follow up to assess (1) reasons they were involuntarily admitted (if applicable), (2) whether they wanted treatment prior to being admitted, (3) their feelings about being “coerced” into treatment, (4) their experiences during the involuntary admission process, and (5) suggestions for what they believe could have been done differently.

The researchers were specifically interested in evaluating (1) differences in motivation at admission between patients who were voluntarily vs. involuntarily admitted for treatment (i.e., “legally coerced” without mention of specific criterion, policies, or procedures), and (2) whether motivation measured at baseline was associated with substance use outcomes at six months post-discharge. The researchers described each treatment center as “similar,” comprised of multidisciplinary providers (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, etc.), and having a primary focus of treating substance use disorder. Each unit was co-ed and monitored by staff to ensure patient safety. These were not locked units but patients who wished to go outside were accompanied by staff. Patients were able to receive visitation from friends and family, received regular urine toxicology screens, and received pharmacotherapy, cognitive therapy, and motivational enhancement interventions on the unit.

There were 65 involuntary patients and 137 who were admitted voluntarily into the study. They ranged in age from 18 to 61; the median age of the involuntary patients was 24 and the median age for voluntary patients was 28. 34.6% drank alcohol, 19.3% used heroin, 17.8% other opiates, 50.4% benzodiazepines, 50.4% used amphetamines, 50.9% used cannabis, and 14.8% used cocaine, inhalants, and hallucinogens. 69.8% had a co-occurring mental health diagnosis in addition to substance use disorder, 51.9% used drugs intravenously, 51.4% reported a previous drug overdose, and 46.5% had a previous suicide attempt. Lastly, only 8.9% had more than a high school education with the rest reporting primary or high school education, and 14.8% were employed, 86.1% received public welfare benefits, and 26.7% received financial support from friends/family, while 35.1% supplemented their income through illegal activity.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Compared to voluntary patients, involuntary patients had lower readiness to change but similar readiness for treatment.

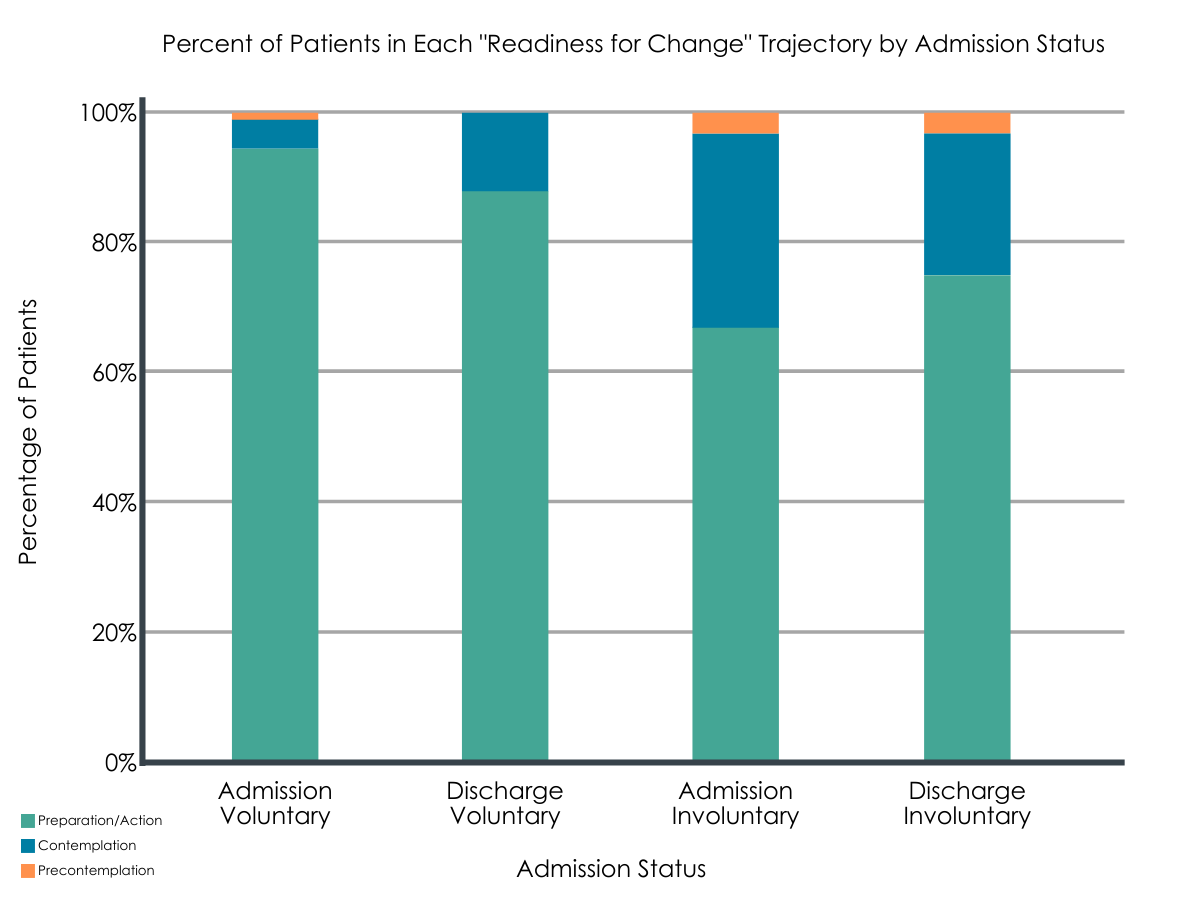

Compared to voluntary patients, involuntary patients had lower readiness to change but similar readiness for treatment. At the same time, motivation to change substance use was still unexpectedly high among members of both groups, and two-thirds of the involuntarily admitted patients were motivated for treatment at admission, despite refusing treatment previously.

When interviewed six months later, 75% of involuntarily admitted patients acknowledged that they needed treatment and felt positively about having been mandated to attend.

The remainder of these patients felt negative about having been mandated (e.g., “humiliated” as described by some).

Contrary to the researchers’ expectation, motivation for change in early treatment was unrelated to substance use at 6 months.

Figure 1. Depiction of the percentage of voluntary vs. involuntary patients and their reports of “readiness for treatment” at admission vs. discharge.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Involuntarily admitted patients were less motivated to change initially, though motivation was unexpectedly high, and readiness for treatment was similar for both groups. Further, motivation at admission was unrelated to drinking outcomes six months later. When interviewed six months post-discharge, 75% of patients who were involuntarily admitted believed in hindsight that treatment was needed and felt positively about having been mandated to attend.

The implications of this study are that individuals with significant concerns about their substance use, or who have incurred negative consequences as a result of their substance use, recognize a need for treatment and report relatively high motivation to change substance use and seek/attend treatment whether or not they are voluntarily admitted. Related research in the United States (U.S.) supports this, and documents similar perceptions of the treatment and long-term outcomes among voluntary and involuntary/mandated patients.

These findings and others from the U.S. suggest that mandated or involuntary treatment might provide an opportunity for individuals with SUDs to access needed treatment. At the same time, further research on patients’ particular change goals could inform involuntary treatment policy, promote matching patients to the appropriate level of care (e.g., outpatient vs. residential vs. inpatient), and expand intervention options that are consistent with patients’ diverse treatment needs and preferences (abstinence vs. moderation or harm reduction).

There is little information provided in the current study about the manner of admission to treatment. It is important to consider the different policies and practices around involuntary admission, and the impacts of these policy and practice differences on patient outcomes. This is true when it comes to understanding the direct impacts on substance use over time, but also patients’ sense of autonomy, personal responsibility, and the perceptions of trust in providers and systems of care.

The finding that motivation for treatment, measured at admission and discharge, was unexpectedly high and remained relatively stable over time is a positive sign. Related research demonstrates similar perceptions of treatment and long-term outcomes among involuntarily/mandated patients in the U.S. as well. Nevertheless, it still important to investigate differential outcomes based on involuntary admission practices. For example, unlike the current study, involuntary treatment in the U.S. is often a criminal justice matter, where involuntary hospitalization may be handled by local law enforcement and practices for getting individuals into treatment can vary widely (e.g., police escort, family escort, private “for hire” transportation services). It is also important to consider differential outcomes among patients depending on the type of program to which they are mandated. For example, outcomes following involuntary admission to inpatient or residential may differ compared to outpatient treatment settings, where there is less intensive and structured therapeutic support and fewer opportunities for patients to develop cohesion.

The fact that the only predictor of patient outcomes long-term was severity of substance use at baseline (e.g., injection drug use) suggests that additional predictors should be considered, as well as enhanced assessment and intervention support to engage those who are more severe with continuing care following discharge.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The authors excluded from analysis patients who did not complete at least three weeks of treatment, which significantly undermines generalizability of the findings. The authors also did not report on rates of dropout from the study or premature discharge against medical advice (AMA) over time.

- The authors do not specify the goals of the patients included in the study (e.g., goal of abstinence vs. goal of harm reduction or substance use in moderation).

- The authors do not provide any information about the nature of the involuntary admission process, making it impossible to compare these results to those of other countries, such as the U.S., whose policies and practices may differ considerably.

- The authors did not find that motivation to change substance use, measured at baseline, predicted abstinence six month follow up. However, this measure was developed to assess motivation and the need for motivational enhancement or other brief interventions in early treatment, not necessarily long-term outcomes. Measures that assess patients’ commitment to sobriety have been shown to outperform measures like those used in this study, and may be more suitable to the study of long-term abstinence.

- “Voluntary” patients may still be in treatment due to other kinds of more subtle social coercion from spouses, family members, or employers who are concerned about their welfare as well as the effect on the family or work.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Involuntarily admitted patients had high levels of motivation for change (broadly defined) and treatment, suggesting they are interested in addressing their SUD. The majority of patients who were admitted involuntarily and interviewed six months later reported feeling grateful for the treatment they received, and related research from the U.S. suggests perceptions of treatment and long-term outcomes might be similar whether voluntarily or involuntarily admitted. Thus, mandated treatment might provide an opportunity for individuals with SUDs, particularly those who are criminally involved and/or a threat to themselves or others, to access and benefit from needed treatment. At the same time, it is important to maintain respect for individuals and promote autonomy and personal responsibility as much as possible while also seeking out personal and professional consultation as needed to link individuals with treatment suited to their needs (e.g., outpatient vs. residential), preferences (e.g., abstinence vs. moderation), and safety concerns (e.g., risk of harm to self and others). In addition, it is important to keep in mind that motivation for change and for treatment can vary, and it is most often the case that follow up treatment and aftercare are needed following hospitalization.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The authors conclude that while there were differences between patients who were voluntarily vs. involuntarily admitted to treatment on measures of motivation, the relatively high levels among both groups were noteworthy. The authors recommend that providers focus on eliciting motivation from patients to seek treatment following discharge from hospitalization. At the same time, and, given that motivation was not associated with long-term outcomes, it may be important to also assess and seriously consider patients’ motivational barriers leading up to and immediately following significant healthcare transitions (residential to outpatient, involuntary to voluntary). Practical barriers including treatment cost; lack of coverage; familial, occupational, financial responsibilities; and stigma can all undermine treatment seeking. Nevertheless, patients who attend follow up treatment in the month following hospitalization are much more likely to experience positive treatment outcomes.

- For scientists: In the current study, the authors found that motivation for change and for treatment differed between patients who were voluntarily vs. involuntarily admitted, but were still relatively high and stable over time. They did not find that motivation for change predicted abstinence at six-month follow up. Much more research is needed on this topic, especially follow up that examines more precisely the policies and practices involved with involuntary admission. Other measures of motivation might also be important to assess in addition to or in lieu of the motivation measures used in this study. That is, the motivation for change measures is most often used to assess motivation for change early on and used to assess need for motivational enhancement or other brief interventions early in the treatment process. Thus, it may not be appropriate or sufficient in cases where the goal is to predict long-term outcomes. Alternative measures that assess patients’ commitment to sobriety have been shown to outperform measures like those used in the current study and may be more useful predictors of long-term abstinence. It will also be useful to consider patients’ personal motivations, whether they be for total abstinence, harm reduction, or moderation. Lastly, it may be helpful to also collect data on behavioral markers and predictors of long-term outcomes, such as treatment engagement, adherence to treatment and recommendations, and engagement in follow up care, for example.

- For policy makers: The authors note that despite differences in the motivation to change and seek treatment among patients voluntarily vs. involuntarily admitted, motivation was still relatively high and stable across groups. This study and others provide evidence that counteracts some concerns about the negative effects of involuntarily admission for substance use treatment, which document positive perceptions of treatment and as good or better outcomes among patients who are mandated or involuntarily admitted to treatment. Future research may be needed to study the effects of various involuntary admission practices, as well as patient outcomes depending on the mandated type and level of care (e.g., inpatient vs. outpatient, moderation vs. abstinence-based).

CITATIONS

Opsal, A., Kristensen, Ø. & Clausen, T. (2019). Readiness to change among involuntarily and voluntarily admitted patients with substance use disorders. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 14(47), 1-10. doi: 10.1186/s13011-019-0237-y