Opioid agonist treatment in jail and prison: What can we learn from the trailblazers?

Incarcerated individuals with a history of opioid use disorder are at increased risk of overdose and death should they remain abstinent during incarceration (resulting in loss of physiological tolerance to opioids) and return to opioid misuse upon release. Opioid agonist medications like buprenorphine and methadone are shown to prevent overdose and death when provided to incarcerated individuals and, although these medications are not widely used in jails and prisons in the United States, a few have started to offer such programs. In this study, the researchers conducted qualitative interviews with correctional system leaders to identify facilitators and barriers to providing buprenorphine and methadone treatment for opioid use disorder within jails and prisons in the United States.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Individuals with opioid use disorder have a higher likelihood of incarceration compared to those without opioid use disorder, and one-quarter of incarcerated individuals have opioid use disorder. When these individuals enter prison or jail and lose access to opioids, abstinence results in decreased physiological tolerance, increasing their risk of overdose and related death should they return to opioid misuse at levels similar to pre-incarceration, upon release.

Opioid agonist medications, such as buprenorphine and methadone, help prevent overdose during active treatment, and studies suggest that agonist treatment during and after incarceration benefits incarcerated individuals just as much as community-based medication treatment benefits non-incarcerated individuals.

Despite the effectiveness and life-saving nature of these medications, they are not widely used in jails and prisons across the United States. It may be that the logistics of administering agonist medications (e.g., need for medical staff, concerns over diversion) to inmates and the finances needed to start up and maintain such programs are potential barriers to providing them in correctional facilities. However, the use of medication treatment in correctional facilities has started to grow and the experiences of correctional systems who are trailblazing these treatment programs can help to inform other jails and prisons looking to initiate successful treatment programs of their own.

Identifying the barriers and facilitators faced by jails and prisons that currently implement these treatment programs may help us better identify new ways to support the initiation and maintenance of treatment in prisons and jails. Doing so can ultimately help reduce risk of overdose and better support community re-entry among incarcerated individuals. In this study, the researchers conducted interviews with leaders of opioid agonist treatment programs within correctional facilities to identify barriers and facilitators to providing methadone and buprenorphine in United States jails and prisons.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The research team conducted qualitative interviews with 35 individuals who work at jails and prisons in the United States that offer individuals the opportunity to start and continue opioid agonist treatment (buprenorphine or methadone) during incarceration.

Participants were all leaders within their systems (i.e. 19 jails and prisons, and 1 correctional system healthcare company), who were responsible for establishing or overseeing their treatment programs, including medical directors, mental health service directors, and wardens. Correctional facilities that only offered medication treatment to select groups of people (e.g., only pregnant women) or for short-term medically managed withdrawal were excluded. Of the 19 correctional systems, 14 were county-run jails, 2 were state-run prisons, and 3 were unidentified jail or prison systems within the larger umbrella of state-run systems. One system offered buprenorphine maintenance only (without offering initiation to individuals who were not on medication at the time of incarceration) and 16 offered both buprenorphine initiation and maintenance. Regarding methadone, 6 systems offered methadone maintenance but not initiation, and 10 offered both initiation and maintenance. All systems offered extended-release injectable naltrexone (opioid antagonist) in addition to opioid agonist treatments.

Interviews were conducted between August 2019 and January 2020. Interviews involving security staff, senior medical staff, and other leadership (e.g., data managers) occurred at 6, 16, and 5 facilities, respectively. Interview topics covered four themes, including: 1) adopting opioid agonist treatment programs within correctional facilities, 2) how policies influence the implementation of these programs, 3) the structure of such treatment programs, and 4) patient outcomes for opioid agonist treatment within prisons and jails. The researchers identified and coded themes among interview responses, which were assessed as the primary study outcomes.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

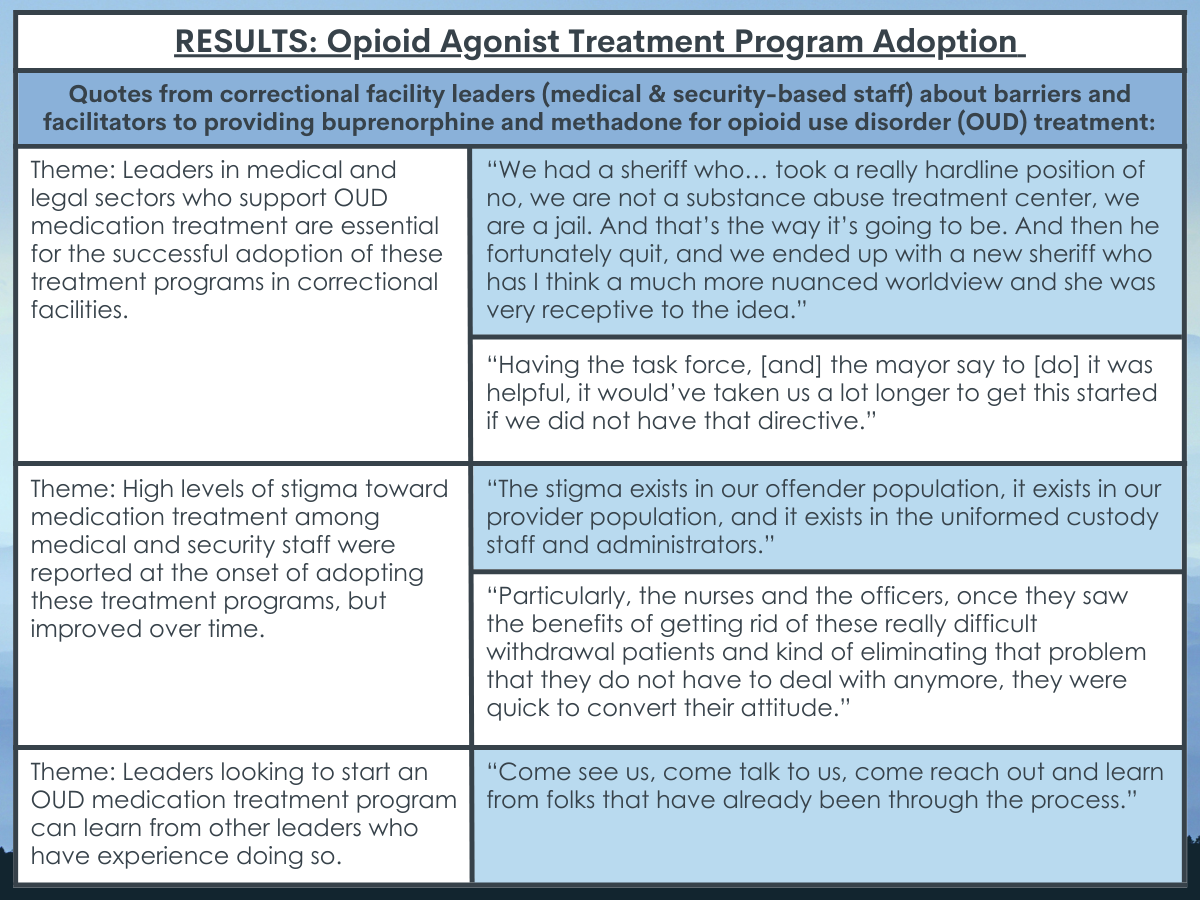

Adoption of opioid agonist treatment programs depended upon the support and guidance of leadership, and the ability to overcome stigma.

Security staff and elected officials who are supportive of implementing medication treatment were seen as essential for successful program adoption. Treatment programs were also seen as better off when healthcare providers at correctional facilities were affiliated with community-based public health systems (e.g., local hospitals), as opposed to being for-profit contractors hired by correctional systems. Medical and security staff at jails and prisons noted stigma toward medication treatment, with supportive leadership helping to reduce this stigma, and stigma reducing over time with exposure to the treatment’s benefits. Learning from the experiences of other leaders with established treatment programs was noted as a key component to starting and building a successful program.

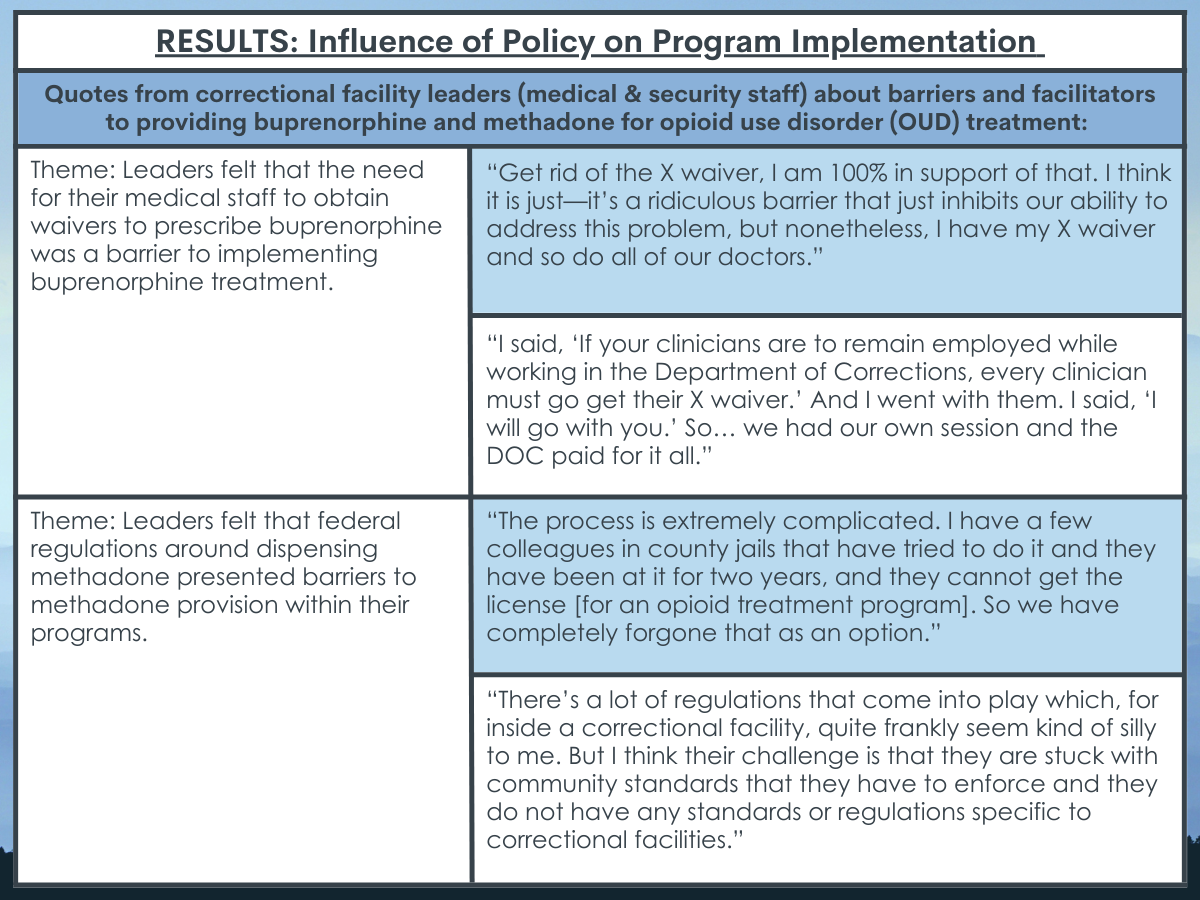

The interpretation of laws and compliance with legal restrictions around dispensing opioid agonist medications was a challenge to implementing it.

At the beginning of implementing the treatment program, many leaders thought that the need for medical staff to obtain waivers to prescribe buprenorphine, and the prescribing limits set by the waiver, restricted their ability to bring on more inmates who may have benefited from the program.

Leaders noted that requiring or providing incentives for medical staff to obtain buprenorphine waivers helped to combat these challenges. Instead of becoming licensed as an opioid treatment program, many leaders decided to partner with community-based opioid treatment programs, which was seen as easier but also required substantial resources (e.g., daily transportation of patients to the community-based methadone clinic).

Aspects of the program’s structure that posed challenges included determination of treatment eligibility program requirements, dispensing procedures, and re-entry services.

Prescriber availability and inmates’ fear of repercussion for reporting opioid misuse were seen as challenges to identifying eligible individuals and initiating them on medication treatment.

Since not all correctional facilities offer medication treatment, there were also difficulties around starting treatment in those who might ultimately be transferred to a facility without medication. Substantial resources (staff, space, time) were also needed to ensure dispensing regulations were followed and diversion was limited. Many leaders reported deviating from evidence-based practices to prevent diversion in their facilities (e.g., dose & treatment-duration limits), with some prescribing the same dose to all patients regardless of their clinical needs. Though many systems made follow-up appointments with community providers for patients due to be released, many inmates were released without warning which hindered post-release plans, and less than half of the facilities provided patients with an interim prescription or medication upon release.

Having strong partnerships with community medical providers was seen as key to continuing treatment after release and preventing overdose. Intensive follow-up by medical staff in the initial days following release and the use of peer navigators were also thought to improve the likelihood that patients would attend their first community appointment.

Though medication treatment programs were thought to benefit inmates and the correctional facility procedures/environment, the ability to provide these services was limited in scope.

Several leaders reported that the provision of medication treatment in their facilities reduced inmate disruptions and self-harm attempts. A couple of systems also reported that their programs resulted in fewer deaths and reduced need for naloxone (overdose reversal drug) in their facilities. Limited staff, funding, and space, as well as strict eligibility criteria limited the number of inmates who were able to participate in the program, with less than 20% of their eligible inmate populations receiving medication treatment. Regardless of these challenges, leaders agreed that medication treatment services should be offered in more jails and prisons and that other leaders are becoming more accepting of the idea of medication treatment in their facilities.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study helps us better understand what may or may not work for adopting and implementing a successful opioid use disorder medication treatment program within correctional facilities. With relatively few jails and prisons offering such services, and growing interest in these programs, it is essential to identify the barriers and facilitators to developing and maintaining opioid agonist treatment programs within correctional systems. Doing so can ultimately inform new laws and regulations that encourage and better support corrections-based medication treatment across the United States to better address the ongoing opioid and overdose epidemic.

Consistent with community-based treatment research, the adoption of buprenorphine and methadone treatment programs in jails and prisons depended on the support of leadership in various legal and healthcare roles. Supportive leadership was also perceived as a key facilitator to reduce stigma toward medication treatment, emphasizing the need for leadership education and the importance of hiring program management that is supportive of opioid agonist treatments for opioid use disorder. Importantly, treatment programs in correctional facilities that utilized community-based healthcare providers reportedly facilitated the adoption and startup of these programs. This highlights the possibility that involving medical professionals with community-based treatment experience may help to promote program adoption and correctional staff buy-in. Thus, medication treatment programs in correctional facilities might benefit from partnering with community-based buprenorphine prescribers as well as opioid treatment programs that offer methadone.

Given the lack of formal guidance on the logistics and procedures around prison- and jail- run medication treatment programs, learning from the experiences of other leaders with established medication treatment programs appears to be an important facilitator to establishing these medication treatment programs. With many leaders in this study expressing an eagerness to share their experience starting and maintaining their programs, peer-based guidance may be a useful and cost-effective tool to support other leaders in successful program startup.

Laws and legal restrictions around dispensing various opioid agonist medications can be challenging to interpret and were seen here as barriers. For example, the need to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine and the patient limits on these waivers can present obstacles. Medical professionals have to take the extra time to obtain these waivers and, once obtained, the number of patients they can prescribe buprenorphine to is limited. Increasing the number of patients that can be treated under a given waiver and offering incentives for medical professionals who obtain buprenorphine waivers may ultimately help increase the number of patients who can engage in and benefit from these programs in correctional facilities.

With regard to methadone, it seems that additional support and resources are needed to help correctional facilities provide this medication. Strict methadone dispensing regulations and the high cost and long wait to become licensed as an opioid treatment program (which would allow a facility to dispense from within their jail/prison) deterred leaders from seeking internally run methadone treatment programs. Though partnering with community-based opioid treatment programs is a useful alternative, it also requires substantial resources – these might include staff to transport incarcerated individuals to a community-based methadone clinic daily, the need to rely on a community provider to attend and dispense the medication at the correctional facility, or formal agreements that only provide facilities with a limited amount (1-2 weeks) of methadone to dispense at the jail/prison. Given the limited resources and strain that many methadone clinics are already under serving their general communities, new policies are needed to ensure a more streamlined process for providing methadone in correctional facilities that help reduce burden to both community- and corrections- based treatment sectors.

Regarding stigma, studies have shown that exposure to opioid agonist treatments and direct observation of their benefits predict more positive attitudes toward these medications. Thus, sharing positive stories about the benefits of these programs to correctional facility staff and to individuals who engage in them might help facilitate positive attitudinal changes during program startup. New policies and regulations that better support jails and prisons in their ability to provide evidence-based practice without increasing risk of diversion are also needed to better promote acceptance of treatment in incarcerated individuals and prevent opioid overdose among them when re-entering the community. Extended-release injectable formulations of buprenorphine may be a possible way of addressing diversion concerns and promoting the use of these medications in correctional facilities. Since discontinuation of medication treatment and re-entry into the community can increase risk of overdose and death, additional structural and programmatic support to ensure access to interim medication upon release and intensive linkages to community treatment programs are needed. Strong partnerships with community treatment providers will help support patient transitions from jail or prison to the communities in which they live. Additional financial resources may also be warranted to allow for intensive follow-up of patients and peer navigators, which can facilitate successful transfer of patient care.

Medication treatment in jails and prisons was seen as a benefit to correctional facilities, reducing inmate disruptions, self-harm attempts, deaths, and the need for the opioid reversal drug, naloxone. Given that less than 20% of a given inmate population received medication treatment, additional resources are needed to increase the staffing, funding, and space for such programs. Taking these barriers into consideration may help inform best practices for further adoption and implementation of medication treatment programs within correctional facilities, as they expand throughout the United States.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study did not include a focused evaluation of extended-release naltrexone and additional research is needed to characterize the barriers and facilitators to providing this medication as well as patient treatment and recovery outcomes upon release.

- Few facilities had collected formal program evaluations from patients, limiting our understanding of patient experience and satisfaction with the treatment they received.

- This was a qualitative study and quantitative research is needed to better understand operational procedures and program characteristics that predict successful outcomes for patients, including an evaluation of best treatment practices during incarceration and ideal linkages to promote patient success after release from jail or prison.

BOTTOM LINE

This qualitative study found that correctional facility leadership perceived many barriers to initiating and maintaining a medication treatment program in their facilities, including lack of resources (e.g., staffing, funding, space), regulatory barriers around dispensing agonist medications (buprenorphine waivers & special methadone dispensing laws), staff stigma toward medication treatment, difficulties providing patients with medication should they anticipate a transfer to a non-medication-providing facility, and community linkages to continued treatment upon inmate release. However, there was also some aspects that were thought to facilitate adoption and implementation of medication treatment in jails and prisons, including leadership who are supportive of opioid agonist treatment, incentives that encourage medical staff to obtain buprenorphine waivers to increase the program’s patient capacity, partnerships with community opioid treatment programs to aid their ability to offer/provide methadone and ensure ongoing treatment post inmate release, having jail and prison healthcare providers that are affiliated with community healthcare systems, engaging peer-leadership who have previously established medication treatment programs, and using intensive follow-up and peer navigators to facilitate ongoing treatment upon community re-entry.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Currently, methadone and buprenorphine are not widely available for individuals with opioid use disorders while incarcerated, though the availability of programs that offer such medications during incarceration are beginning to expand. Medication could be a potentially helpful option to seek out during incarceration, as well as after release from jail or prison.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Given that prisons and jails perceived community-based healthcare professionals as a benefit to adopting and implementing opioid agonist treatment programs in correctional facilities, prescribers might consider supporting the expansion of such programs by contributing their expertise to the correctional system. Partnering with jail and prison systems might also help facilitate inmate transitions to community-based care upon release, which could ultimately help patients’ continuity of care and reduce overdose rates among recently incarcerated individuals.

- For scientists: Additional research, including quantitative research is needed to replicate and extend these findings in various correctional settings, and to identify additional barriers and facilitators to adopting and implementing these programs across various legal systems. Investigation of all available medications (including antagonists and extended-release versions of these medications) could help further our understanding of cost-effective program and treatment characteristics that expand availability of treatment to more inmates, prevent overdose upon release, and better support correctional staff and improve jail/prison environments.

- For policy makers: Though opioid agonist medications (buprenorphine and methadone) are effective life-saving medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder, opioid agonist treatment is not widely available in jails and prisons throughout the United States. Additional programmatic and research funding will help to expand opioid treatment programs in correctional facilities, which will ultimately help to better address the opioid and overdose epidemic. Given the barriers associated with strict opioid agonist dispensing regulations and their limited applicability to the correctional system, new laws that specifically pertain to medication treatment in jails and prisons may help to streamline operations and clarify terms and conditions to better guide correctional facilities looking offering medication treatment within their systems.

CITATIONS

Bandara, S., Kennedy-Hendricks, A., Merritt, S., Barry, C. L., & Saloner, B. (2021). Methadone and buprenorphine treatment in United States jails and prisons: lessons from early adopters. Addiction, 116(12), 3473-3481. doi: 10.1111/add.15565