What is the evidence for residential treatment? A review and update

Residential treatment for substance use disorder (SUD) accounted for 18% of treatment admissions in the US in 2017. However, some experts have questioned whether there is enough research evidence to support recommending such a time- and cost-intensive treatment approach. This systematic review updates the evidence.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The value of residential treatment for SUD has been a primary focus of research and debate among experts. Many clinicians, patients, and advocates feel that residential treatment is a critical first step in the recovery process, especially for those with more severe SUD, because it provides immediate safety and stabilization and minimizes or eradicates the chances for use of alcohol/drugs However, the evidence in favor of residential treatment (compared to other approaches) is not as strong as one might expect. Some studies have found that people who attend outpatient treatment, especially intensive outpatient programs (which provide treatment multiple times per week), fare just as well as those in residential treatment.

Research has generally shown that residential treatment is helpful, but that there is minimal evidence that it is better than less intensive approaches. However, there are a number of factors that make it difficult to draw solid conclusions based on the research to date. First, many residential treatment studies exclude potential participants who are considered too “high risk.” This means that their SUD is too severe, or that other social factors that are common for people with SUD, such as unstable housing, make randomly assigning them to a treatment type risky and unethical. As a result, much of the highest-quality research leaves out this important group of clinically complex treatment seekers. The wide variety of residential programs, which vary in length, types of treatments offered, and other factors, is also a challenge to drawing general conclusions about residential treatment through research. Importantly, residential treatment for SUD is expensive and time-consuming, and can be disruptive to the lives of individuals with SUD. If this approach does not provide added benefit above less expensive or disruptive approaches, such information would be critical for providers, individuals with SUD, and anyone else involved in such decision making.

In order to provide an update on the state of the research evidence, the authors of this study identified and reviewed the most recent published studies of residential SUD treatment. Systematic reviews like this one are useful because they consolidate information from multiple studies into a single paper, highlighting commonalities and differences in findings. Given the historical challenges in conducting high-quality research on residential SUD treatment, the authors evaluated each study for methodological quality. They also summarized key study characteristics and findings, including the types of residential treatment evaluated, the types of outcomes measured by each study, and the findings themselves.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a systematic review, meaning the authors searched academic databases using a specific set of search terms, then used a predetermined set of requirements to systematically identify the search results to include in the review. For this study, the authors used specific search terms to identify research published between 2013-2018 that evaluated residential SUD treatment for adults. They removed any search results that did not meet their inclusion criteria, including any that did not report their findings numerically (i.e., were not quantitative), were not community-based (i.e., took place in prisons or psychiatric hospitals), or were focused on adolescents under 18 years of age. From an initial results list of 834 studies, 23 were original (e.g., not duplicate results) and met these criteria.

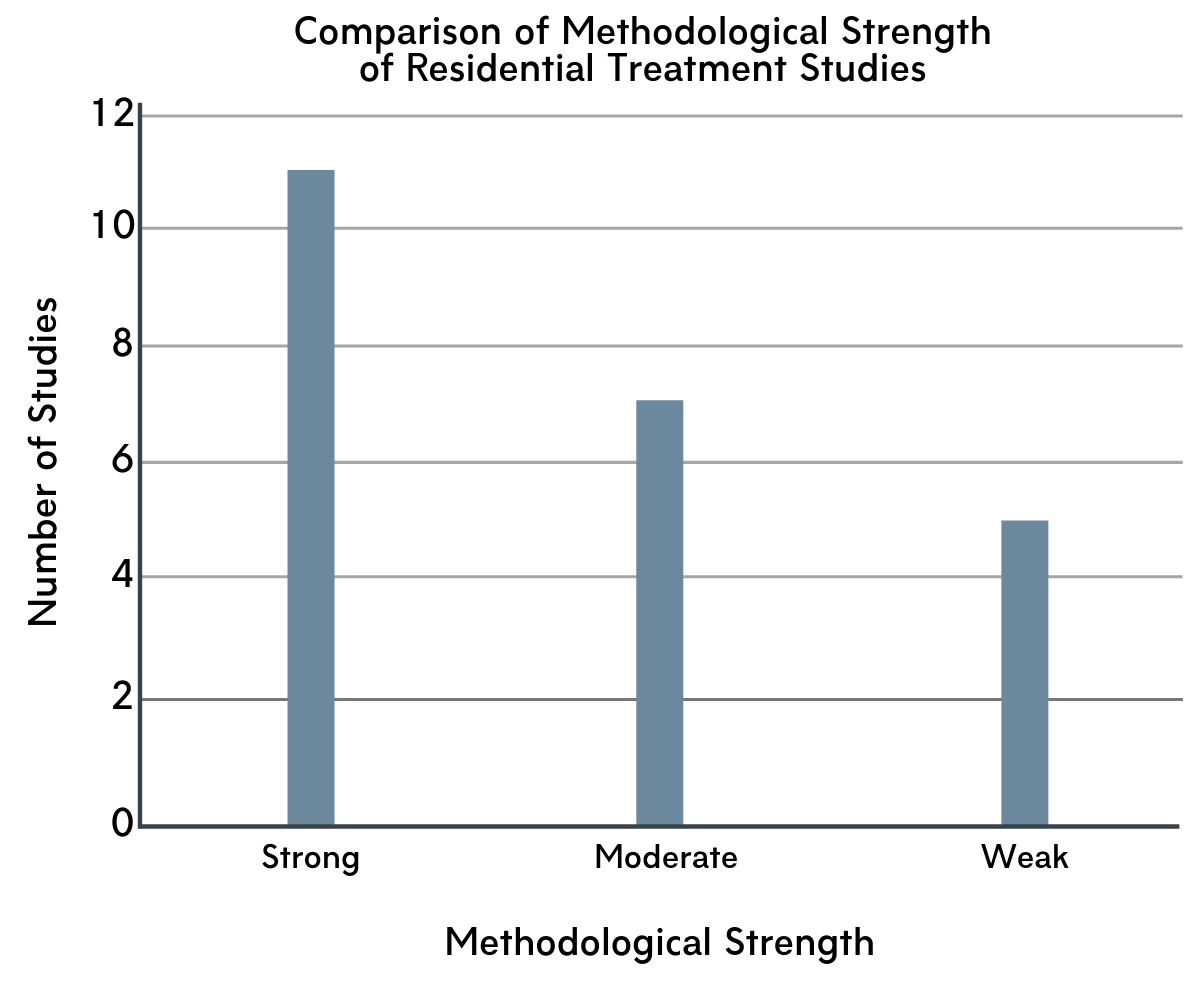

To evaluate the quality of each study’s approach (e.g., “methodological strength”), the authors used a system called the Effective Public Health Practice Project’s (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. This scoring system uses a number of factors to assign each study an overall rating of “weak,” “moderate,” or “strong.” These include the strategy used to identify participants, the number of participants who dropped out before the study ended, and other design characteristics known to affect study results, such as whether people are randomly assigned to an active or comparison condition.

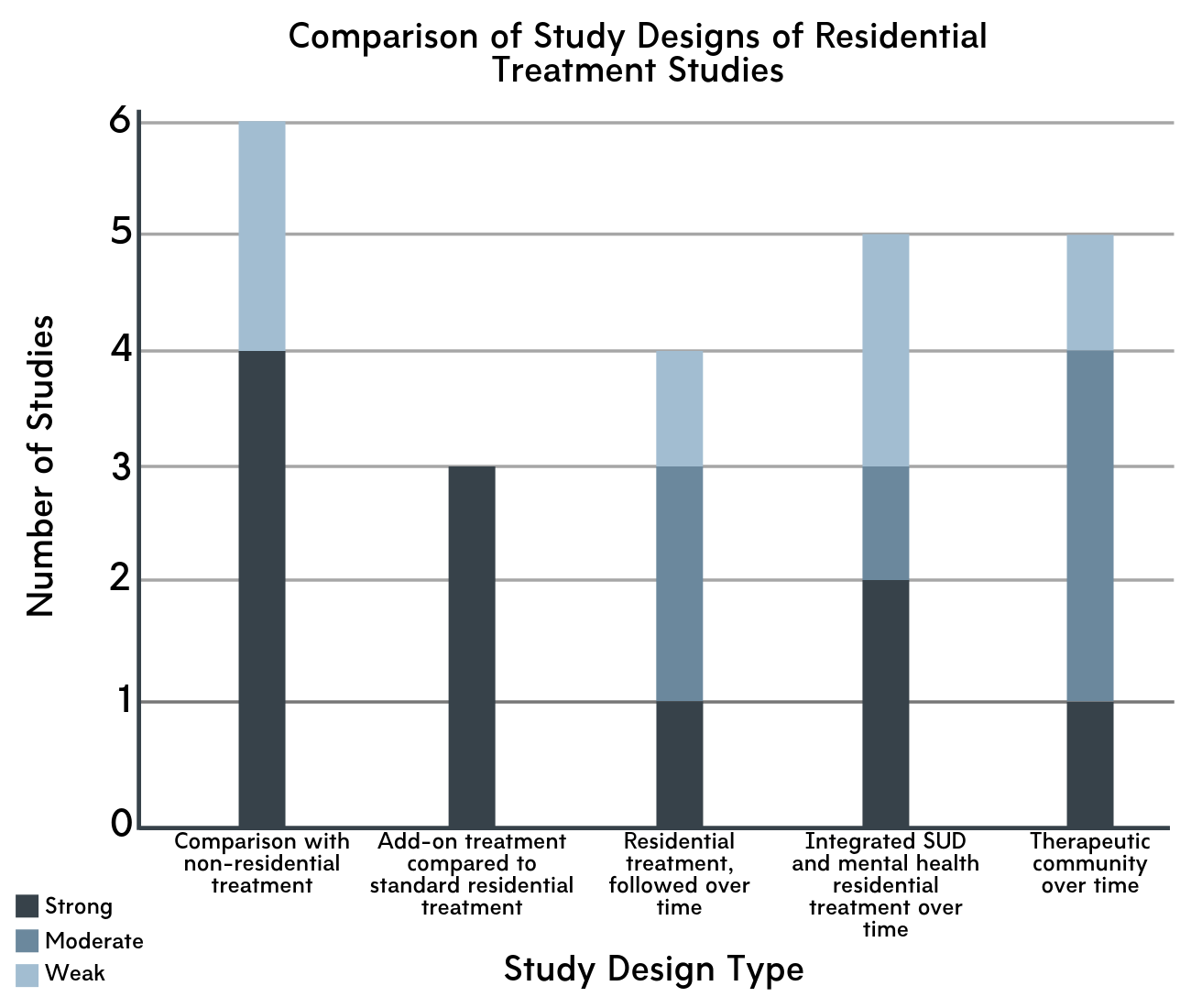

The authors then summarized key components of each of the 23 studies. This included information about the study’s approach, such as whether it followed one group over time or compared two or more different groups. They also summarized the types of findings reported by each study, and the results themselves, which covered a number of areas in addition to substance use outcomes, including information about participants’ mental health, legal involvement, and mortality.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The authors found that the methodological quality of the research on residential treatment appears to be improving compared to prior reviews of residential SUD treatment, with 18 studies meeting criteria for strong or moderately strong methods. They also summarized the design of the studies they identified, including whether a study compared residential treatment to a different form of treatment (the most rigorous approach), or followed a single group of participants across time.

Figure 1. Methodological strength of studies compared.

Figure 2. Study designs compared across residential treatment research.

The authors included studies which used a broad range of methodological approaches, including analyses of country-wide registry data through to smaller scale studies within a single treatment program. The studies also examined a broad range of residential program types, with features such as treatment approach and length of stay (e.g., one month to a year) varying widely. Studies that compare residential treatment to another type of treatment provide a better sense of effectiveness than studies that only follow residential treatment participants over time. Thus, we focus on these comparison studies, then review findings from the others as well.

Residential Program Outcomes Compared to Other Approaches

Six studies compared residential treatment with non-residential approaches on a variety of outcomes. These comparisons reported mixed results with respect to the added benefit of residential treatment. Some reported more positive outcomes in residential treatment, including higher rates of abstinence, fewer re-admissions to substance use treatment, and more treatment completion. One reported superior outcomes for a therapeutic community approach, which emphasizes peer roles in treatment, compared to standard residential treatment, though this study was rated as methodologically weak. Others were less positive, reporting that residential treatment, compared to other approaches, had the least impact on legal involvement, and that those who attend residential facilities (in the course of standard treatment) are more likely to die in the year after discharge (though this was likely due to higher severity, as discussed in more detail below).

Three more studies compared typical treatment in residential programs with added support of some kind. The add-on components were all psychosocial therapy offerings (e.g., mindfulness-based relapse prevention), and reported generally better outcomes compared to those completing residential treatment as usual.

- Substance Use Outcomes

-

Substance use outcomes were reported by most (17) of the studies. The majority of these reported significant changes over the course of treatment, rather than differences between treatment settings. Studies generally found that individuals who attended residential treatment experienced improvements in substance use outcomes over time. Those that had fewer people complete their follow ups tended to report better substance use outcomes. In these cases, it is likely that the subset of participants who did follow up were doing better than those who did not (commonly known in research as “attrition bias”).

- Mental Health Outcomes

-

Of the 17 studies reporting on mental health-related outcomes, the vast majority of residential treatment attendees experienced improvements in mental health symptoms over time. Again, the majority of studies reported on changes for individuals over the course of their treatment. The types of outcome varied, from symptoms associated with a specific diagnosis such as post-traumatic stress disorder through more general mental health and functioning.

- Social Outcomes

-

All of the studies (11) that measured outcomes related to social well-being and functioning reported improvements over time among residential treatment attendees, using measures ranging from broad quality of life to more specific social outcomes such as employment and finances.

- Legal Involvement

-

Of the nine studies that looked at legal outcomes for participants, six used the same general measure and reported reductions in overall legal involvement for participants. The rest looked at specific legal outcomes, with one strong quality study reporting that, over a two-year follow-up period, recorded offenses were lower for those who attended detoxification or community-based medication treatments, but not for those who attended residential treatment.

- Mortality

-

One study looked back at records for people who had attended different types of SUD treatment, and tracked deaths that occurred within twelve months after treatment for the sample. While this study reported higher death rates for those who attended inpatient detoxification and residential treatment, the observational approach suggests that these individuals likely had more severe SUD to begin with, which could have explained their greater likelihood of mortality.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Overall, the authors found that those who attend residential treatment appear to experience improvements in substance use, mental health, and broader social outcomes. However, support for residential treatment, especially as it compares to other approaches, continues to be moderate at best, as concluded by previous reviews. While the methodology of the research appears to be improving, the challenges of such work, including an evolving variety of treatment approaches and a difficult–to–monitor population, are a continued issue. The authors provide recommendations that fit within the broader research in this area, highlighting the importance of care continuity after discharge from a residential program, as well as monitoring and reporting outcomes related to broader functioning. They also note the potential value of linking study information with legal, mortality, and other public health records to monitor outcomes after treatment admissions.

Given the continued equivocal findings, and the pragmatic challenges with research in this population, it is likely that certain types of residential treatment are an important part of the recovery process for certain individuals with SUD. Identifying these critical factors continues to be an important topic for SUD researchers. This review cast a wide net with respect to program and participant characteristics, which is a strength in that it helps to reflect the broader treatment system. However, the relevant factors that are beginning to emerge from other research would be missed in such an approach. For example, there is some evidence that residential treatment is more effective for people who use certain substances, such as opioids. Here it is also worth mentioning that while residential treatment programs historically would not include opioid use disorder medications such as buprenorphine (often prescribed in a formulation with naloxone, known by the brand name Suboxone), this practice is changing, and some residential treatment programs have integrated medication management into their treatment models. In order to determine who will benefit most from residential treatment, and what residential treatment factors are most responsible for these benefits, future studies will need to examine such factors.

While the variety of residential treatment options was a key challenge of this review, some approaches from the broader continuum of residential options were not included. The studies included in the current review ranged widely in terms of typical length of stay, from one month to a full year. However, longer term sober living environments were excluded. For example, one peer-driven residential sober living format, known as Oxford Houses, appears to provide positive outcomes for people following a residential admission, and also results in lower costs to the public as a result of these improvements. Given that cost of residential treatment is a critical aspect of the debate regarding its relative value, such approaches are critical to consider. Many complete multiple treatment episodes across a number of years before gaining an extended period of remission, which again highlights the importance of care continuity.

Another takeaway from this review study is the importance of understanding a study’s methods before drawing conclusions about findings. An example that illustrates this well is the article reporting higher mortality for people who attended residential treatment compared to those who attended outpatient programs. This study did not assign participants to conditions, but rather linked existing health records with death records. In this case, individuals with more severe SUD, who have a higher risk of death, were probably more likely to attend residential treatment. Without a careful review of these methods, it is possible to misread these results as evidence of the potential harm of residential treatment. Of course, there may also be an increased risk of death following residential treatment programs, for example, due to practices such as discharging individuals with opioid use disorder without medication treatment. However, because of the study methods, it is impossible to identify the cause of this increased mortality.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study is a systematic review, rather than a meta-analysis, which is a more powerful way to consolidate research findings across studies. Meta-analyses are able to merge specific findings across multiple studies on, for example, percent days abstinent after leaving residential treatment. However, as the authors note, given the small number of methodologically “strong” studies, and the wide variety of approaches and results considered, a meta-analysis was not possible for this particular review.

- Another challenge with systematic reviews is that interpretation of study findings can depend on review authors’ perspectives. For example, the authors of this review included a study by Teesson and colleagues which focused on identifying different patterns of substance use for a large group of individuals over a period of 10 years following treatment. This review included the study as an example of residential treatment outperforming outpatient treatment with medications for opioid use disorder. However, while the percentage of individuals who attended residential treatment and had no decrease in heroin use over time was lower than those in agonist treatment, there were no statistically significant differences between different treatment histories and heroin use trajectories over time in that study.

- Attrition was high in many studies in this review, so it’s difficult to truly consolidate the findings in a valid way. This is perhaps the most critical challenge with evaluating the effectiveness of treatment approaches over time for individuals with SUD, whose lives are often so seriously impacted that it is difficult for researchers to keep in contact with them. A related complication is the broad range of time periods covered by the studies in this review. The treatments themselves ranged from one to twelve months in length, with follow up periods from less than one year to multiple years post-treatment. It is difficult to meaningfully comment on attrition and outcomes with such wide variation. It is also difficult to make general conclusions about the effect of “residential treatment” with such wide variation in length of stay and treatment approach.

- The study did not include cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness analyses, therefore the question of whether residential treatment is worth the extra cost remains unanswered.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This review provides updated evidence in support of the potential benefits of residential treatment for those with SUD. However, neither this review nor previous reviews have concluded that residential treatment is the only option. In fact, people in comparison groups, who typically attend outpatient treatment, often do as well as those in residential programs. It is important to remember that the programs evaluated here were largely evidence-based, which means the treatments they provided had been evaluated in previous research. Treatment programs that offer evidence-based interventions, including both psychosocial treatments and medications, provide accessible information about their treatment approach, that monitor and report on their outcomes, and provide good strong linkage to follow-up care, are likely the best options.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed that the evidence in support of residential SUD treatment continues to be moderate, partly due to the challenges inherent in conducting research in such a high-risk population. This is a critical reminder that residential treatment is not the only path to recovery, and that some individuals can and do recover without a period of residential treatment. However, more work needs to be done to better define which groups of individuals, in particular those with SUD, are most likely to benefit from such intensive treatment. Monitoring outcomes using measurement-based practice at the local level is a fast, efficient way to make decisions within a specific system. Some updates from the research reviewed includes recommendations for emphasizing continuing care, broader outcomes including broader functioning and well-being, as well as co-occurring mental health conditions.

- For scientists: More rigorous research on the true utility of residential treatment is needed, because people are spending a lot of money in programs, and high-quality studies continue to be few and far between. It is also critical to continue examining outcomes with respect to participants’ broader functioning. Of course, it is likely not a matter of whether residential treatment works, but rather which residential treatments work, and for whom, and how length of residential stay is related to outcomes. Partnering with clinicians and policy makers to examine longer term outcomes both within and beyond the treatment system is a key recommendation from the current review.

- For policy makers: This review provides evidence to support providing access to residential SUD treatment. Since the quality of the evidence is moderate, there may be moderating factors (types of patients) who benefit most from this approach. Until it is possible to more effectively assess for treatment fit, residential programs provide sufficient value to merit continued access among those with SUD. The issues of cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness remain and were not included in this review. Policy makers can assist by supporting the provision of high-quality residential treatments like those reviewed by this study, earmarking funds that allow researchers to examine the utility of residential treatment, and by continuing to facilitate researchers’ efforts to monitor outcomes more reliably through linkage with administrative datasets.

CITATIONS

de Andrade, D., Elphinston, R. A., Quinn, C., Allan, J., & Hides, L. (2019). The effectiveness of residential treatment services for individuals with substance use disorders: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 201, 227-235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.031