The road in vs. the road out: A new mindset may help separate beliefs about the causes of SUD from beliefs about the recovery process

Recent calls to frame addiction as a chronic medical condition are intended to reduce stigma experienced by individuals with substance use disorder (SUD). By emphasizing the fixed, uncontrollable causes of the condition, however, this framing may inadvertently lower an individual’s confidence in being able to benefit from treatment. In this study, authors considered whether framing SUD as a condition that can be overcome would increase confidence and interest in seeking different types of treatments without increasing self-blame.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

SUD is among the most stigmatized conditions in the world. The stigma and shame resulting from perceptions of addiction as a personal choice are important barriers to treatment-seeking among individuals with SUD, who attend treatment at lower rates than those with other mental health conditions. The “disease model” has been promoted as a response to this harmful messaging because it frames addiction as a medical condition worthy of treatment.

Unfortunately, some research has shown that emphasizing stable “medical” causes of certain conditions, such as obesity, might actually decrease interest in some forms of treatment. Specifically, thinking of a condition in this way can decrease people’s confidence and interest in growth-oriented interventions like personal goal setting and psychosocial treatments. In this way, it is possible that the “disease” model of addiction may inadvertently reduce individuals’ confidence in their potential to benefit from these (evidence-based) options for managing SUD.

To explore this question, authors in this study tested whether individuals who screened positive for SUD and were exposed to a more growth-oriented framing of the disorder would report greater confidence in being able to change, and greater intention to seek psychosocial treatment, without exacerbating self-blame for developing SUD.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This experimental study recruited participants online using a crowd-sourcing website called mTurk. Participants were included if they reported using alcohol or drugs and endorsed at least one item on the CAGE-AID, which asks four questions that may indicate an SUD (e.g. “In the last three months, have you felt guilty or bad about how much you drink or use drugs?”).

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Each group read a brief blog-type article written by the study authors about the causes and treatment of SUD. These articles were created by the study authors and included references to fictional research and experts (i.e., that study authors created themselves) in support of each narrative. Participants then answered questions relating to their beliefs about addiction and interest in treatment.

In the “compensatory-growth” group, participants read an article that noted the fixed factors contributing to the development of addiction but focused on the potential for effectively managing the condition through growth-oriented personal efforts, including treatment engagement across modalities.

The other article, read by those in the “disease-fixed” group, focused on the genetic and biological contributors of addiction, and described fictional research and expert quotes supporting the fixed nature of the condition, highlighting how difficult it is to treat and the high likelihood of relapse.

Figure 1.

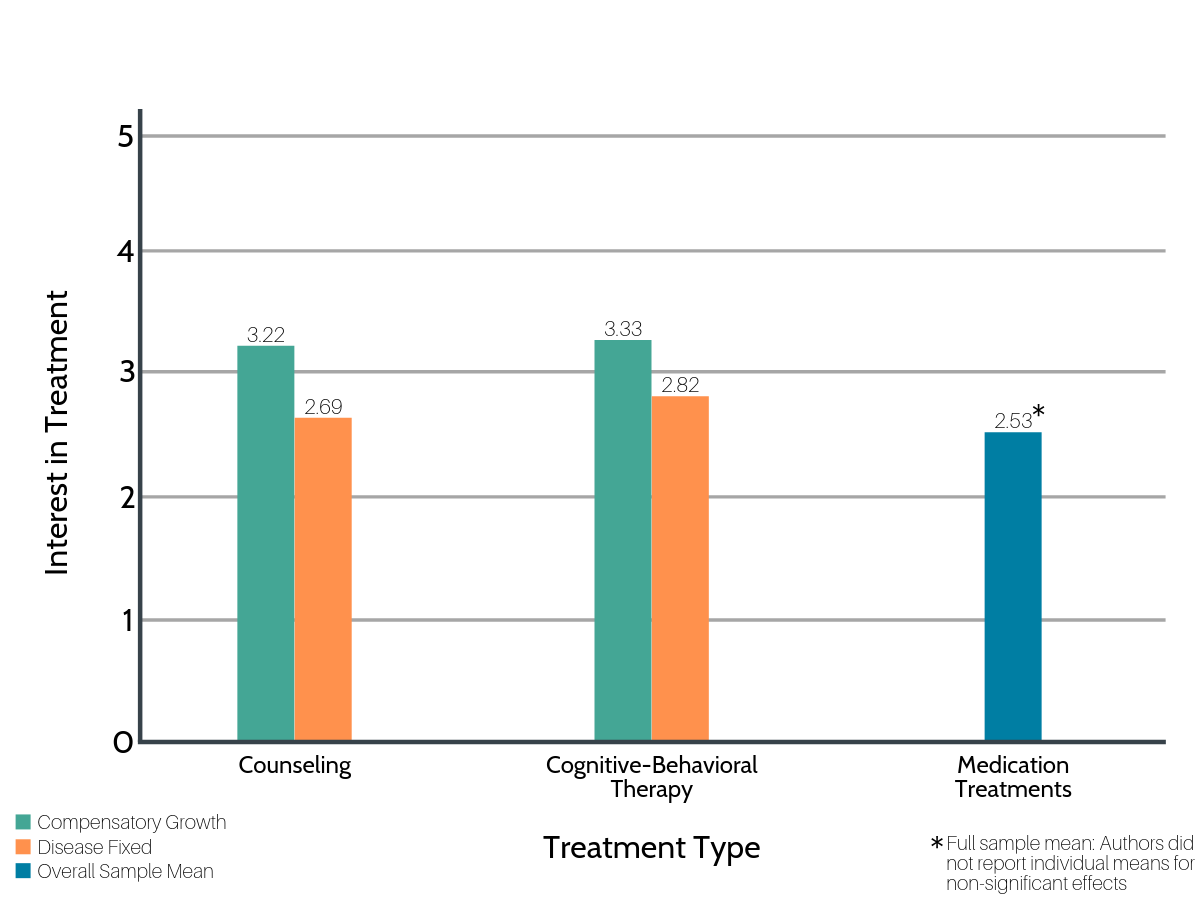

The primary outcome of the study was participants’ reported interest in different types of addiction treatment after reading the brief article. Both groups were asked to rate their willingness to seek three types of treatment for their substance use: counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, and pharmacological treatment.

The study also examined whether participants showed differences in their thinking about addiction after reading the different passages. Using measures adapted from similar studies on mindset and change beliefs in weight management research, the authors measured participants’ belief in the possibility of changing one’s ability to effectively manage an addiction (i.e., “growth mindset”), personal responsibility for having the condition (i.e., self-blame), and confidence in their ability to manage their addiction currently (i.e., self-efficacy).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Participants who read the passage emphasizing potential for growth (the “compensatory-growth” condition) reported higher interest in seeking counseling or cognitive-behavioral therapy than those in the other (“disease-fixed”) condition.

Interest in medication treatment was similar between groups, suggesting that higher interest in behavioral treatments did not negatively impact openness to medication treatments.

Figure 2.

Participants in the “compensatory–growth” group also agreed more strongly with “growth” mindset statements, suggesting that reading the passage influenced their responses to these items. They were also more confident in their ability to make changes to their substance use in the future (i.e., greater self-efficacy). However, “compensatory-growth” group participants were no more likely to blame themselves for having an SUD than those in the “disease-fixed” group.

Figure 3.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

There is growing evidence that the way we communicate (and think) about SUD impacts individual treatment–seeking as well as the beliefs of friends, family, and treatment providers. While the disease model has potential value in its ability to shift the perception of others, it may have mixed effects for individuals with SUDs. Prior related studies highlighted the alarming possibility that the disease model might actually reduce confidence in behavioral treatments and personal goal setting by emphasizing the uncontrollable causes of addiction too strongly.

In a similar type of vignette study with participants from the general population, McGinty and colleagues showed that portraying SUD – opioid use disorder in this particular example – as a treatable medical condition resulted in less stigma. Thus, framing SUD as a condition that individuals can resolve by engaging in treatment and other change efforts may have been responsible for participants’ greater intentions to seek treatment in this study. Given that the compensatory–growth vignette framed SUD as treatable, while the fixed-disease vignette outlined a study suggesting treatment does not help, future work is needed to truly tease apart what types of messaging will help individuals with SUD foster confidence to change and seek quality treatment without increasing self-blame.

This innovative study sought to consider the potential downsides of a common approach to describing SUD. The science regarding the impact of language in SUD will need to be a topic of ongoing research. For example, the authors only measured participants once immediately after reading the vignettes and did not follow participants over time. This study, therefore, represents only an initial test of this theory. While participants in the “disease-fixed” condition did report lower interest in counseling and cognitive behavioral therapy on average, the magnitude of these effects was relatively small. Future work will also need to evaluate baseline beliefs before any attempt is made to change people’s mindsets, test whether changes in mindset are lasting, and whether they are associated with actual treatment–seeking and outcomes. Importantly, the finding that self-blame and interest in medication treatments were similar between groups suggests this new approach is not harmful.

Research on communication about SUD is constantly evolving, and the disease model may certainly have some meaningful limitations. For example, the disease model may also oversimplify the range of severity represented by alcohol and substance use disorders and limit people’s understanding of how treatment could help those with less severe forms. Alternatively, framing the causes of substance use problems as multidetermined, and emphasizing the options, may encourage treatment–seeking among those with less severe use problems. This group represents the largest portion of individuals impacted by substance use, and they are at high risk of increased severity and premature death.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The online crowdsourcing website mTurk is a valuable resource for providing affordable access to a diverse pool of potential research participants. While workers on this website generally appear to provide truthful information, there are a number of challenges with using this approach. Participants are more susceptible to social desirability effects, and therefore may be more likely to answer in the way they perceive the experimenter wants them to. Further, this study did not report “expertise” numbers for participants, which is the number of tasks previously completed on the website. This is an important consideration, especially with respect to completion of similar studies, as there is evidence that completing many similar tasks over time may bias results.

- The authors recruited participants who reported problems related to their substance use but may not have met formal criteria for SUD. This approach led to some important limitations. For example, the outcome measures used the word “addiction” after screening only for substance use and related consequences. So, while participants had endorsed at least one consequence of their use (most commonly, feeling guilty about use at least once in the past three months), they did not necessarily identify as having SUD. As a result, they may have been more likely to answer outcome questions (such as “I can change my ability to manage my addiction to alcohol or drugs”) in the way they perceived the experimenters expected. Many participants were likely to be on the mild end of the SUD continuum, where people tend to be less likely to see a need for treatment. These participants may also have approached the survey in a more hypothetical way. The inclusion of people reporting all forms of substance use may also have masked important differences within the sample, as there is some evidence that mindset is less important for those who use certain substances, such as heroin.

- The study did not ask about people’s mindset before reading the vignettes, only after. This format makes it difficult to know whether there were any group differences beforehand. It also makes it difficult to determine how much the articles themselves lead participants to select what they considered to be the “right” answers, due to a common (largely unconscious) research phenomenon known as “demand characteristics.”

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study highlights the value of emphasizing the role of personal growth and multiple types of treatment for managing an SUD without introducing blame for the disorder itself. By thinking about SUDs as medical conditions that can be managed by a “multi-pronged” approach – medication, therapy, and personal efforts – it is possible to take ownership of the recovery process without placing blame on an individual for the development of the condition or setbacks along the way.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study presented an adaptation to the disease model of addiction that may improve help-seeking, because research on other health conditions suggests that focusing too much on “fixed” causes of a condition can limit people’s interest in therapy and active problem-solving. The disease model is commonly used in clinical settings to reduce stigma and self-blame, and it emphasizes the lack of control inherent in SUD. Providers and treatment systems may want to be mindful about separating the framing of the causes of SUDs from the causes (or processes) of recovery. In other words, emphasizing personal agency in the recovery process may increase individuals’ confidence and willingness to seek behavioral treatment without increasing self-blame.

- For scientists: This single-session randomized experimental study showed that participants who read an article emphasizing the value of personal growth and multiple treatment formats for managing addiction were more open to behavioral treatments and more likely to think in a growth-oriented manner than those who read an article emphasizing the fixed nature of addiction as a disease. While it is important to consider the potential ways in which messaging about addiction may be inadvertently impacting individuals with SUD, the disease model as presented in real-world contexts may not be fully reflected by the stimuli used in this study. Given the experimental approach with a non-clinical sample, and vignettes that were confounded by framing SUD as treatable in one but not the other, it will be important to confirm that disease model messaging and resulting mindset genuinely parallels findings from the obesity research cited by the authors.

- For policy makers: This study is an initial examination of one potential downside of the “disease model” of addiction, based on evidence that focusing on “fixed” causes may reduce individual confidence in growth-oriented behavioral treatments for medical conditions. While this study did not provide sufficient evidence to conclude that the disease model is causing harm by reducing help-seeking, focusing on the importance of persistent efforts and multiple forms of evidence-based treatment to manage addiction could very well be a helpful emphasis in communication and policy development. Perhaps the most important take-home, however, is the importance of attending to the evolving nature of best practices for communication regarding SUD, as research continues to highlight the real impact of such messaging on those in the community.

CITATIONS

Burnette, J. L., Forsyth, R. B., Desmarais, S. L., & Hoyt, C. L. (2019). Mindsets of addiction: Implications for treatment intentions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 38(5), 367-394. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2019.38.5.367