“Buyer beware”: Treatment admissions practices and costs of residential treatment for opioid use disorder

Residential treatment accounts for one quarter of the United States’ spending on substance use disorder treatment and, for those with the highest severity, may be a first step on the road to recovery. This study, however, raises concerns that some residential treatment programs may be admitting clinically and financially vulnerable people without properly assessing the appropriate level of care.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Among the general public, residential treatment is often seen as the first step on the journey of recovery and many policy makers call for the expansion of treatment beds in response to the overdose crisis. Studies of individuals who attend residential treatment show positive outcomes and enhanced recovery-related functioning over the short-term. At the same time, multiple studies have shown that only a minority of people in recovery from opioid use disorder and other substance use disorders have attended residential treatment. Additionally, the quantity and quality of the evidence supporting the effectiveness of residential treatment is much less when compared to other treatment options. Researchers still know relatively little about what makes residential treatment effective in those case where it does help. The situation is further complicated by the fact that residential treatment programs vary by length of stay, staffing configurations, philosophical approach, and services offered, making comparisons across different residential programs difficult.

In the treatment of opioid use disorders, specifically, there are two federally approved agonist medications (Methadone and Buprenorphine) shown to reduce the threat of overdose by at least half. Yet, a recent survey found that a minority of residential treatment programs offered access to these medications. When examining first treatment received after an opioid use disorder diagnosis, receipt of agonist medications such as buprenorphine for 6 or more months is associated with reduced overdose risk, but residential treatment is not associated with this reduced overdose risk. The American Society for Addiction Medicine has standard criteria to determine the appropriate levels of care for people struggling with various types of substance use disorders, which does include recommended use of residential treatment for more severe cases. That being said, the substantial majority of people who resolve a substance use problem do not receive, nor require, residential treatment—which can be both costly and may unnecessarily remove people from their homes and work situations. Many respond well to much less expensive outpatient level care, and, especially for opioid use disorder, this can include medications. Despite this, many desperate families and individuals seek residential treatments on their own. In recent years, there have been anecdotal reports of predatory recruitment to residential treatment programs, over charging, and sexual abuse of patients.

To better understand the admission practices and costs of residential programs in the United States, this study called treatment providers, posing as a person using heroin who was interested in entering their program.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In June 2019, the researchers compiled a list of residential treatment programs using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMSHA) Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. They excluded programs only providing short-term “detoxification,” transitional housing, and programs administered by Federal and Tribal governments. In order to capture programs not listed on SAMSHA’s website, the researchers employed a search analytics company to identify additional programs through the provider’s purchase of web advertising. On this basis, they obtained a target sample of approximately 600 programs, 368 of which they managed to contact, 81% of which responded. Three trained staff posed as a 27-year-old person actively seeking treatment for their heroin use with no other health issues and no insurance coverage. The callers followed a standard script and detailed notes were taken on each call. The researchers coded the calls (a method of content analysis) and analyzed the result using statistics.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

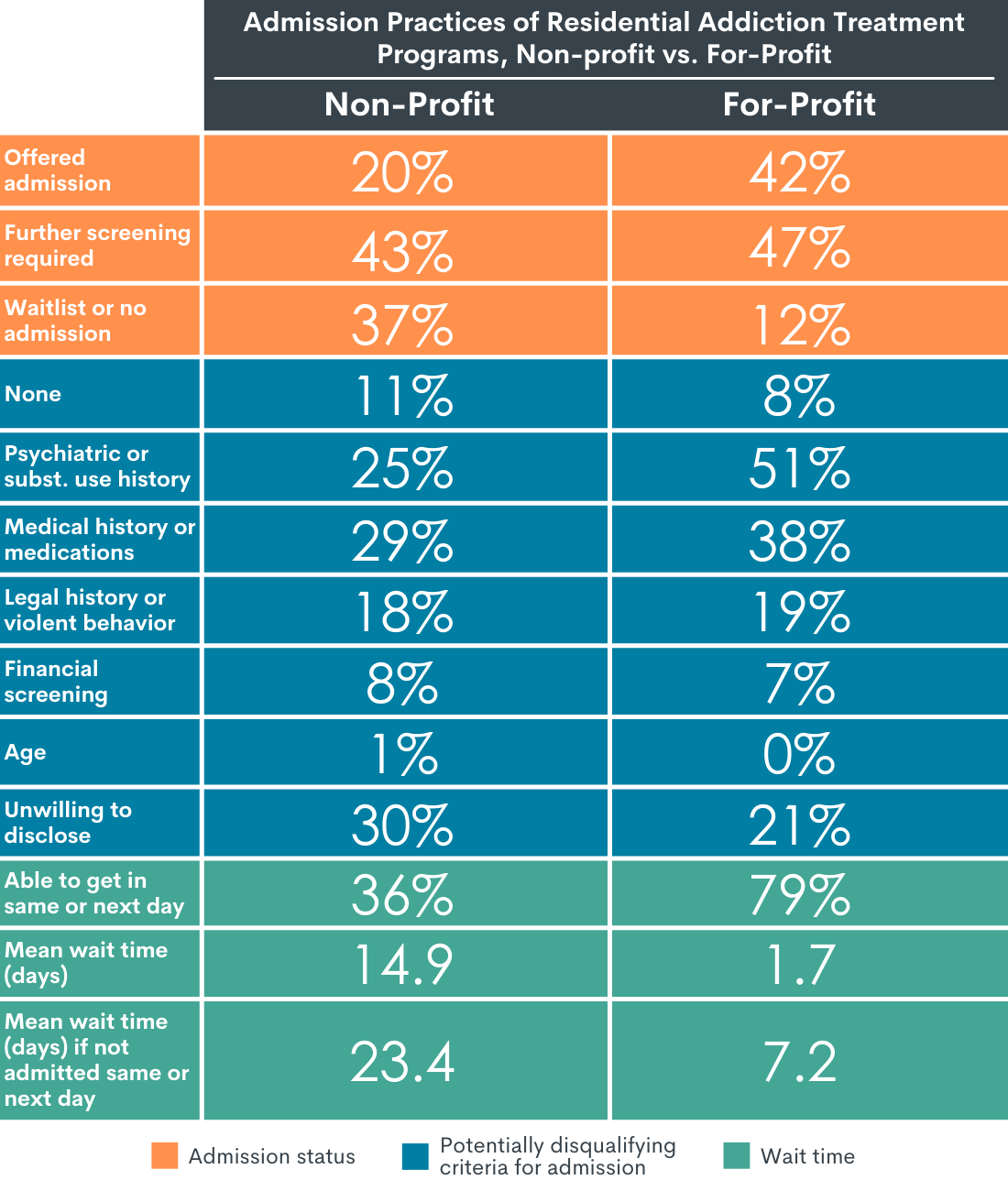

Among the respondents, 42% of for-profit programs offered admission over the phone without screening or pending an intake evaluation. Many for-profits programs disqualified potential patients with psychiatric or substance use history other than heroin (51%), medical history (38%), legal history or prior violent behavior (19%), and financial history (7%). Sixty-five percent of for-profit programs used recruitment techniques to persuade callers to enter their program. These included promoting luxury amenities or justifying cost based on quality (31%), offering assistance with transportation or encouraging travel (19%). Thirty-two percent of these for-profit programs offered to talk to family members and 30% offered to maintain contact after the call.

In the case of for-profit programs, 79% of programs offered same day or next day admission. The average wait time if not admitted the same day was 7.2 days. The average cost of treatment was $758 a day and 88% of for-profit programs required up-front payment. Seventy-nine percent of for-profit programs offered admission without insurance. Twenty percent encouraged using credit to pay for treatment; 17% offered a payment plan.

Figure 1.

In contrast, 20% of non-profit programs offered admission over the phone without screening or pending an intake evaluation. Some non-profits programs disqualified potential patients on the basis of psychiatric or substance use history other than heroin (25 percent), medical history (29 percent), legal history or prior violent behavior (18 percent), and financial history (8 percent). Only 9% of non-profit programs used a recruitment approach to convince patients to enter the program. These included promoting luxury amenities or justifying cost based on quality (3%), offering assistance with transportation or encouraging travel (4%). Six percent of for-profit programs offered to talk to family members and 3% offered to maintain contact after the call.

In the case of non-profit programs, 36% of programs offered same day or next day admission. The average wait time if not admitted the same day was 23.4 days. The average cost of treatment was $357 a day and 50% of non-profit programs required upfront payment. Fifty-eight percent of non-profit programs offered admission without insurance. Six percent encouraged using credit to pay for treatment; 11% offered a payment plan.

In summary, non-profit admission practices differed considerably from those of for-profit programs. Non-profits were less likely to offer admission over the phone, less likely to exclude patients based on their psychiatric or substance use history, and less likely to use recruitment tactics. Non-profits had longer wait times for admission on average and a lower likelihood of encouraging the patient to take on debt to pay for treatment. In comparison to for-profit programs, non-profit programs have less than half the same-day admission rate and about three times the average wait time. For-profit program costs, on average, were more than twice the amount of non-profit programs per day.

Finally, the majority of programs that responded were accredited by the Joint Commission or the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities. Thirty-seven percent of accredited programs offered admission to callers and 53 percent used recruitment techniques. In other words, accredited programs were more likely than non-accredited programs to offer admission before full clinical evaluation and utilize inducements.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

These results point to disparities in access to residential treatment related to financial ability and substance use disorder severity. They suggest that individuals who cannot afford for-profit programs face significant obstacles to accessing treatment in a timely fashion. At the same time, the more stringent exclusion criteria employed by for-profit programs, especially regarding co-morbid mental health conditions and other substance use history, raise the possibility that more severe cases of substance use disorders are being funneled toward less accessible, non-profit programs. This effect is of particular concern since American Society for Addiction Medicine criteria suggest that residential treatment is the appropriate intervention for this more severe group.

The results also raise questions about how well individuals are screened to ensure that inpatient treatment is the appropriate level of care. A large proportion of for-profit programs (42%) offered admission without clinical screening or pending an intake evaluation. Although it is unclear as to how many patients would have been admitted without proper evaluation in practice, these numbers suggest that a sizeable number of for-profit programs are accepting individuals with inadequate screening. Given that some programs develop their own evaluation criteria or utilize the American Society for Addiction Medicine (ASAM) guidelines “loosely,” this problem may be even more widespread than this data captures. Some non-profit programs also appear to be screening patients inadequately, although the percentage is much lower (20%).

This study also raises concerns about the use of recruitment practices and inducements. Strikingly, these are rare among the non-profit programs surveyed (9%). In contrast, they are utilized by almost two-thirds of for-profit programs (65%). This is an important area for further inquiry. Some of the practices described by the researchers, such as hard sell techniques and advising individuals to rely on debt to pay for treatment, are potentially coercive and self-serving. Other practices, however, such as providing transport to treatment, may in fact facilitate access. Still others appear more-or-less neutral, for example describing the quality of food at a facility.

While these findings concern a minority of (largely for-profit) treatment programs from across the country, they nevertheless raise larger questions about the potential exploitation of a clinically and financially vulnerable population. In turn, such abuses point to ways that some programs are incentivized to prioritize profits over best practices and high-quality clinical care. The results of this study suggest the need for a broader, system-wide conversation about how to protect patients from exploitation and make accessible services to the patients with the greatest severity and/or less financial resources. Accomplishing these goals may require, among other measures, stronger government regulation of residential treatment programs as well as a more transparent and standardized system for tracking program quality indicators and outcomes across the industry.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As the researchers acknowledge, the treatment programs in this study were not a randomly chosen or representative sample. It was an observational study of a large number of programs and the researchers were informed about the programs that they contacted. These results should not be treated as representative. Nevertheless, the size of the study suggests that the reported practices may be to some degree widespread.

- The caller posed as an uninsured person who uses heroin; thus, the study may not capture outcomes relevant to insured patients or to others with different types of substance use problems.

- 3. There was a higher rate of study non-response by non-profit than for-profit organizations. Given the significant differences between the non-profit versus for-profit programs, this imbalance may have further weighted the aggregate findings in the direction of for-profit programs.

- 4. The researchers report programs that offered admission without screening in the same statistic as programs that offered admission pending an intake evaluation. Although they state that “typically” the intake evaluation would not have affected admission, the presence of an intake screening blurs the line between programs with and without proper clinical evaluations. It is not possible to infer how many programs would have admitted patients with inadequate or not any screening in practice.

- Although the researchers acknowledge that some recruitment practices may be beneficial (providing transport, for example), they report potentially helpful and potentially harmful recruitment practices together. This agglomeration may create a misleading impression of how wide-spread harmful recruitment practices and inducements are.

- The researchers reported on whether the caller was screened for admission with a clinical evaluation. But they do not give details about the nature of the screening or whether the screener used an evaluation, such as the American Society for Addiction Medicine (ASAM criteria), that is recognized within the field. Many programs create their own screening and admission standards; some treatment facilities that utilize the American Society for Addiction Medicine (ASAM) criteria employ them “loosely.” Given this inconsistency in practice, the problem of inappropriate admissions to residential treatment may be more widespread than this study suggests.

- While medications for opioid use disorder are often described as the “gold standard,” they do not work for a significant number of patients (up to a quarter in some studies). Additionally, a sizeable minority of people do not wish to take medications. For these groups, residential treatment may be a critically important option. In framing the benefits of medications versus residential treatment for OUDs, the researchers do not take these groups into account.

BOTTOM LINE

Residential treatment accounts for one quarter of the United States’ spending on substance use disorder treatment and, for those with the highest severity, may be a first step on the road to recovery. At the same time, multiple studies have shown that only minority of people in recovery from opioid use disorder and other substance use disorders have attended residential treatment. Additionally, the current evidence supporting the effectiveness of residential treatment is mixed and uneven given variability in lengths of stay, staffing configurations, and types of treatment services offered in such settings.

This study raises concerns that some residential treatment programs may be admitting clinically and financially vulnerable people without properly assessing the appropriate level of care. It points to the need for the thorough integration of American Society for Addiction Medicine, or similar, criteria, to determine more ethically and systematically the appropriate level of care across the treatment system. These results also point to the need for a broader conversation about how to protect patients and make accessible services to the patients with the greatest severity and/or less financial resources. Accomplishing these goals may require, among other measures, stronger government regulation of residential treatment programs as well as a more transparent and standardized system for tracking program practices and outcomes across the industry.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: While residential treatment was the first step for 15% of those who resolve a substance use problem, large variability across different types of residential programs makes it very difficult to know which are likely to be effective. The American Society for Addiction Medicine suggests inpatient treatment only in more severe cases of substance problems. Despite that recommendation, some treatment programs accept patients without screening and employ aggressive recruitment practices. Residential treatment programs differ in terms of philosophy, staffing, length of stay, and services provided. Researchers and advocates have developed tools to help individuals and families assess the quality of programs.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study draws attention to practices by some residential treatment programs that are concerning, especially inadequate clinical screening before admission and the coercive and self-serving use of recruitment techniques. Although these reports represent a minority of programs, overall, such practices are common enough to raise questions regarding the potential exploitation of a vulnerable population. Developing evidence-based standards and independent enforcement is necessary to prevent bad actors from harming the credibility of the industry as a whole. An important step in this direction would be the wider incorporation of American Society for Addiction Medicine – or similar – criteria, into admission screening to ensure that people entering residential treatment are receiving the appropriate level of care. Likewise, outpatient providers should screen clients based on standardized clinical criteria before referring to residential treatment.

- For scientists: Evidence in support of the effectiveness of residential treatment is mixed and we need more research on what specific groups might benefit from which types of programs and services. This study suggests that researchers should also examine potential downsides or harms of residential treatment, especially those associated with common practices like inadequate screening and opportunistic recruitment. In particular, researchers should look at the impact of receiving an inappropriate level of care or “over-treating” given the number of treatment programs that accept patients with inadequate clinical screening. Further research should also examine the impacts of “cherry picking” lower severity and less complex clinical cases while funneling those with more severe substance use disorders and co-morbid mental health conditions toward less accessible non-profit residential programs.

- For policy makers: Although residential treatment can be helpful and lifesaving for some people with substance use disorders, it is costly and the evidence supporting its effectiveness compared to other interventions is mixed. Most individuals in recovery do not attend residential treatment and the American Society for Addiction Medicine only recommends it for more severe cases. This study suggests that there is a minority of treatment providers, especially for-profit providers, that employ aggressive recruitment tactics and may not screen to determine whether residential patient treatment is actually most appropriate. These findings raise the possibility of a vulnerable population being recruited for costly residential treatment when more appropriate lower-level care options are available. Importantly, accredited programs were more likely than non-accredited programs to offer admission before full clinical evaluation and utilize inducements. These results suggest that current licensing and regulation may be insufficient to protect consumers from programs that prioritize profit over real treatment needs. Policies and legislation that promote evidence-based, industry standards and robust enforcement are needed.

CITATIONS

Beetham, T., Saloner, B., Gaye, M., Wakeman, S. E., Frank, R. G., & Barnett, M. L. (2021). Admission practices and cost of care for opioid use disorder at residential addiction treatment programs in the US. Health Affairs, 40(2), 317–325. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00378